Last week Nestle, the world’s largest food processor, was caught in a firestorm when it attempted to censor a Greenpeace campaign that targeted its use of palm oil sourced from a supplier accused of environmentally-damaging practices. The incident brought the increasingly raucous debate over palm oil into the spotlight and renewed questions over an industry-backed certification scheme that aims to improve the crop’s environmental performance.

The palm oil paradox

Palm oil is produced from the oil palm, a tropical species from West Africa that is a highly productive and profitable source of vegetable oil. Its origin—West Africa—makes it well-suited to the tropics and therefore an attractive crop to promote rural agricultural development. But oil palm expansion has often come at a cost to the environment — more than half of new plantations established in Malaysia and Indonesia between 1990 and 2005 occurred at the expense of natural forests. As such, palm oil has been targeted by environmentalists and scientists concerned about biodiversity loss, greenhouse gas emissions, and pollution. Further, the palm oil industry has been challenged by land rights issues, since expansion is occurring in areas where communities may traditionally use forests but lack title to land. New development in these areas spurs charges of land-grabbing and can exacerbate social conflict.

Environmental groups and scientists say that oil palm production has driven large-scale destruction of rainforests across southeast Asia over the past two decades, triggering the release of billions of tons of CO2 and imperiling rare species, including the Sumatran tiger and the orangutan. The palm oil industry maintains that its crop is highly productive, requiring less land and costing less than other oilseeds like soy and canola, and has improved living standards for millions. Industry representatives have tended to dismiss environmental concerns as “colonialism” or masked trade barriers. (Photo: Oil palm plantation and logged natural forest, in Sabah, Malaysia.) |

To address these concerns, in 2004 a group of stakeholders, including NGOs, producers and retailers, formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). RSPO created a set of criteria to make palm oil production less damaging to the environment, including using natural pests and composting in place of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers whenever possible, implementing no burn policies, sparing high conservation value forests from development, taking measures to reduce air pollution, and creating catchment ponds to prevent palm oil mill effluent from entering waterways where it would damage aquatic habitats. The hope was that certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) could be sold at a premium to recoup the increased costs that certification entails.

The first shipments of CSPO arrived in Europe in late 2009. Sales were initially slow, but began to accelerate early in 2010. Nevertheless, the initiative has been battered by a series of scandals, including the recent Nestle debacle and a decision last year by Unilever, the world’s largest buyer of palm oil, to move outside the RSPO process to investigate PT SMART, a supplier accused of failing to maintain RSPO standards for palm oil production (an independent investigation commissioned by Unilever concluded that the allegations were accurate).

RSPO concerns

Not all environmental groups have bought into RSPO. Concerns over the certification standard have been stoked by pictures which activists claim show RSPO members continuing to clear high value conservation forest areas (HCV) in violation of certification protocol. Some critics have labeled RSPO a greenwashing initiative rather than a genuine effort to improve the environmental performance of palm oil. RSPO members have rejected these charges but concede that the certification process is still evolving. Some of the recent troubles for RSPO and the palm oil industry center around Sinar Mas, the world’s largest palm oil producer. Sinar Mas, and its subsidiaries (for example, PT SMART), has been accused by a several environmental groups for egregious environmental transgressions, including destruction of rainforests and peatlands. The accusations have led several of the company’s biggest customers — including Nestle, Unilever, and Kraft — to cancel contracts with it and its subsidiaries. Sinar Mas has responded with a marketing campaign that includes high-profile advertising and attacks on the environmental groups via a pro-palm oil lobby group that portrays itself as an anti-poverty NGO. (Photo: Central Kalimantan – Indonesian Borneo) |

A new paper, published in Conservation Biology, examines why RSPO may be falling short of its promise to clean up the palm oil industry. The authors [*], led by William Laurance of James Cook University and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, argue that the initiative’s objectives are undermined by the composition of its membership, which is dominated by palm oil industry growers, processors, and traders. The apparent conflict of interest results in lax requirements for membership, underfunding ($500,000 budget for a $30 billion-plus industry), a cumbersome complaints process for reporting violations, and lack of oversight and enforcement.

“Clearly, there is much scope for the RSPO to improve its act,” Laurance told mongabay.com. “It needs to get tougher with member companies that are destroying large swaths of primary forest. Otherwise, it risks becoming an apologist for an environmentally destructive industry.”

Laurance and colleagues make a series of recommendations that could improve the environmental sustainability of RSPO, including increasing representation and influence of environmental organizations and experts; developing better monitoring and enforcement capabilities; and taking a stronger stance against deforestation and destruction of peatlands. The authors say the formation of “an independent watchdog group that monitors and critiques the organization, ensuring that it abides by its own strictures” could “greatly increase credibility of the RSPO and its members to the public.”

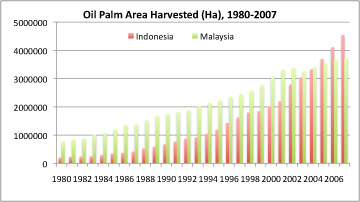

There are other ways to mitigate the impact of oil palm expansion. A new review, published in CAB Reviews, examines some of the options, including setting aside high value conservation areas, land-use advocacy, compensating forest carbon stocks and biodiversity, and enhancing regulation and enforcement. Betsy Yaap et al (2010). Mitigating the biodiversity impacts of oil palm development. CAB Reviews: 5, No. 019. (Photo: Data from FAOstat) |

Ultimately the best incentive for credible RSPO is consumer demand. If consumers demonstrate with their wallets that they want credible eco-friendly palm oil, the palm oil industry will provide it. The cost of “greener” palm oil is not high — especially for buyers in rich countries. A paper I published in January with Lian Pin Koh found that the average American consumer would need to spend an extra 40 cents per year to cover the cost of switching from his or her annual consumption of palm oil from conventional to certified sources. Thus consumers have the power to change the industry.

CITATION: William F. Laurance et al. (2010). Improving the Performance of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil for Nature Conservation. Conservation Biology, Volume 24, No. 2, 377–381 DOI: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01448.x

note: I am a co-author of this paper.

Related articles

Video: Nestle’s attempt to censor Greenpeace palm oil ad backfires

(03/19/2010) In a bold online video, the environmental group Greenpeace cleverly links candy-giant Nestle to oil palm-related deforestation and the deaths of orangutans. Clearly angered over the video, Nestle struck back by having it banned from YouTube and replaced with this statement: “This video is no longer available due to a copyright claim by Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.” However Nestle’s reaction to the video only spread it far and wide (see the ad below): social network sites like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit were all flooded with the ad as well as rising criticism against Nestle—one of the world’s largest food producers—including calls for boycotts.

REDD may not provide sufficient incentive to developers over palm oil

(02/22/2010) In less than a generation oil palm cultivation has emerged as a leading form of land use in tropical forests, especially in Southeast Asia. Rising global demand for edible oils,

coupled with the crop’s high yield, has turned palm oil into an economic juggernaut, generating us$ 10 billion in exports for Indonesia and Malaysia, which account for 85 percent of palm oil production, alone. Today more than 40 countries – led by China, India, and Europe – import crude palm oil.

Commodity trade and urbanization, rather than rural poverty, drive deforestation

(02/07/2010) Deforestation is increasingly correlated to urban population growth and trade rather than rural poverty, suggesting that measures proposed to reduce deforestation will be ineffective if they fail to address demand for commodities produced on forest lands, argues a new paper published in Nature GeoScience.

EU: rainforests can be converted to palm oil plantations for biofuel production

(02/04/2010) The European Union may be planning to classify oil palm plantations as forests, raising fears among environmental groups of expanded conversion of tropical rainforests for biofuel production, reports the EUobserver, which cites a leaked document from the European Commission. The draft document shows that policymakers are considering language that would specifically allow use of biofuels produced via conversion of rainforests to oil palm plantations.

Consumers should help pay the bill for ‘greener’ palm oil

(01/12/2010) Palm oil is one of the world’s most traded and versatile agricultural commodities. It can be used as edible vegetable oil, industrial lubricant, raw material in cosmetic and skincare products and feedstock for biofuel production. Growing global demand for palm oil and the ensuing cropland expansion has been blamed for a wide range of environmental ills, including tropical deforestation, peatland degradation, biodiversity loss and CO2 emissions. In response to these concerns, a group of stakeholders—including activists, investors, producers and retailers—formed the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) to develop a certification scheme for palm oil produced through environmentally- and socially-responsible ways. It is widely anticipated that the creation of a premium market for RSPO-certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO) would incentivize palm oil producers to improve their management practices.

Forest destruction by Sinar Mas undermines efforts to develop and promote greener palm oil

(12/14/2009) An investigation commissioned by Unilever, the world’s largest buyer of palm oil, confirms that Indonesian group Sinar Mas, the world’s second largest producer of palm oil, has been destroying forests and peatlands despite committing to “greener” palm oil production as a member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Unilever has now suspended its $32.6 million contract with Sinar Mas.

Oil palm workers still below poverty line, despite Minister’s statements

(11/19/2009) On October 19th, Plantation Industries and Commodities Minister Tan Sri Bernard Dompok told parliament that oil palm harvesters and rubber tappers are living above Malaysia’s national poverty line, according to a story in the Malaysian Insider. But now representatives of the workers are saying Dompok lied.

Impasse over palm oil emissions at RSPO meeting

(11/04/2009) Environmentalists and palm oil producers meeting at the annual Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) were locked in an impasse over how to account for emissions from converting forests and peatlands to oil palm plantations, report conference attendees.

Palm oil lobby group launches public relations push to counter environmental complaints

(11/02/2009) A report released by World Growth International in late September claimed that environmentalists are waging a “morally indefensible” campaign against palm oil. The report accurately highlighted the high productivity of oil palm — the world’s highest-yielding commercial oilseed — and noted that the crop has created jobs and driven rural development in Malaysia and Indonesia. Critically, World Growth also downplayed chief concerns about the rapid expansion of oil palm cultivation across southeast Asia, notably worries that palm oil production is contributing to deforestation, putting endangered wildlife like the orangutan at risk, and adversely affecting climate. To make its case, the report made some questionable claims, asserting that oil palm plantations sequester more carbon than natural forests and that deforestation is driven by poverty rather than industrial activities.

European companies not supporting ‘greener’ palm oil

(10/29/2009) Most European consumers of palm oil are failing to buy eco-certified palm oil, undermining efforts to encourage producers to reduce their impact on the environment, reports WWF.

Palm oil both a leading threat to orangutans and a key source of jobs in Sumatra

(09/24/2009) Of the world’s two species of orangutan, a great ape that shares 96 percent of man’s genetic makeup, the Sumatran orangutan is considerably more endangered than its cousin in Borneo. Today there are believed to be fewer than 7,000 Sumatran orangutans in the wild, a consequence of the wildlife trade, hunting, and accelerating destruction of their native forest habitat by loggers, small-scale farmers, and agribusiness. Gunung Leuser National Park in North Sumatra is one of the last strongholds for the species, serving as a refuge among paper pulp concessions and rubber and oil palm plantations. While orangutans are relatively well protected in areas around tourist centers, they are affected by poorly regulated interactions with tourists, which have increased the risk of disease and resulted in high mortality rates among infants near tourist centers like Bukit Lawang. Further, orangutans that range outside the park or live in remote areas or on its margins face conflicts with developers, including loggers, who may or may not know about the existence of the park, and plantation workers, who may kill any orangutans they encounter in the fields. Working to improve the fate of orangutans that find their way into plantations and unprotected community areas is the Orangutan Information Center (OIC), a local NGO that collaborates with the Sumatran Orangutan Society (SOS).