A recent PhD graduate of Ohio State University, Sarah Lehnen studies America’s birds with a particular focus on migrating shorebirds. Mongabay.com’s seventh in a series of interviews with ‘Young Scientists’.

Sarah Lehnen has worked with America’s rich birdlife for a decade: she has studied everything from songbirds inhabiting dwindling shrub land in Ohio to shorebirds stopping over in the Mississippi River alluvial valley, always with an eye towards conservation. Most recently she has been involved in testing migratory birds for avian flu.

It may come as a surprise, but American birds are in serious decline. In March of last year, US Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, announced that one-in-three American birds are endangered. Even once common birds are showing precipitous declines. Birds face a barrage of threats, which are only complicated—and heightened—for migratory birds.

Sarah Lehnen. |

“If you think of all the requirements that a bird has over the course of one year: appropriate breeding habitat, safe migratory routes, quality wintering habitat, damage to any one of these components can cause the population to go into decline,” Lehnen told mongabay.com.

But that’s not all, according to Lehnen: “in addition, there are a wide variety of causes of direct mortality to birds, from pesticides, the spread of free-roaming cats, and the proliferation of communication towers, buildings, and wind mills with which migrant birds collide. It’s a dangerous world out there these days for birds.”

Lehnen, who did her PhD work on migrating shorebirds, says that of the 53 shorebirds that breed in North America over half are in trouble according to the US Shorebird Conservation Plan. “It identifies 7 as ‘highly imperiled’ and 21 as ‘species of high concern,'” she explains.

But what makes the conservation of migrating shorebirds particularly difficult is that they don’t heed human-created international boundaries.

“One of the species I’ve worked with most, the pectoral sandpiper, breeds in the arctic of Canada and spends its non-breeding season in Argentina so there are a lot of jurisdictions crossed in a given year with a gauntlet of obstacles to overcome,” Lehnen says, who has studied the pectoral sandpiper in the Mississippi River alluvial valley.

Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melanotos) from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, a US federal subsidiary. |

According to Lehnen, conservation initiatives to truly need to involve the cooperation of each country the bird stops in. To complicate problems even more, every country has different issues to tackle in order to protect birds.

“In the U.S., approximately 50 percent of natural wetlands have been filled or drained and the U.S. continues to lose 24,000 acres (about 35 square miles) of natural wetlands per year. During fall migration, hunters in Barbados use semi-automatic weapons to hunt shorebirds as they move through, with as many as 30-45,000 shorebirds shot each year. In Argentina, solid waste dumped on beaches near Rio Grande and oil exploration using explosive charges in San Sebastian Bay threaten to destroy principal wintering habitat for shorebirds,” Lehnen says illustrating just how complex conserving migratory birds has become.

Due to this complexity, ornithologists at times have difficulty determining which issues are most important in order to aid a particular, or many, migrating bird species. Changes in migration patterns also make it difficult to know whether a population is, in fact, declining or simply holding steady.

“Fewer birds being observed at a migratory stopover site could be caused by a population decline of that species or by birds shortening the length of time they spend at that site, or by birds shifting to different sites,” Lehnen says.

Still, there is little doubt that migratory birds are in trouble and that international cooperation will be necessary to keep these birds in the air.

Pectoral Sandpiper with radio transmitter to track its migration. Photo courtesy of Sarah Lehnen. |

But it’s not just up to nations. Lehnen says that people can help locally by keeping cats indoors, creating a bird-friendly yard, and supporting legislation that aids birds and other wildlife.

“In my humble opinion, even with all the other problems we face as a nation and as a society, we have obligation to ensure that our children inherit as diverse and fascinating a world as we have now. Every species that we lose we lose forever,” Lehnen says.

In a January 2010 interview Mongabay spoke with Sarah Lehnen about the conservation issues facing migratory birds, the unique ecosystem of the Mississippi River alluvial valley, testing for H1N1, and her favorite bird.

INTERVIEW WITH SARAH LEHNEN

Mongabay: How did you become interested in birds? What is your background?

Sarah Lehnen: Although my work has been almost exclusively with birds, I would say my interest is in wildlife in general. When I was growing up in Madison, Wisconsin my parents took me and my brother and sister hiking and camping frequently. Being exposed to the outdoors I developed a curiosity about the natural world. I was a wildlife/biology major as an undergraduate without a focus on a particular taxa until I took a course in ornithology and became interested in birds.

Mongabay: What drew you to working with birds in the United States in particular?

Sarah Lehnen: Mostly it was proximity. Also, the logistics and expense of international travel for research can be cumbersome. I would certainly be open to work on birds in other regions under the right circumstances though.

Mongabay: I have to ask, do you have a favorite bird species?

Audubon’s illustrations of yellow-breated chat. Top: with mating dance. Bottom: after mating dance was removed. 1829. |

Sarah Lehnen: I have a favorite but it tends to changes from day to day. One species that I find consistently endearing is the yellow-breasted chat, a species I worked with for my PhD research. Chats are a bit odd taxonomically; they are grouped with the warblers but have been suspected to being closer related to the tanagers, blackbirds, or mockingbirds. The latest bit I saw on them indicated they aren’t closely related to any of the above. My main draw toward them is their personality; chats are very feisty. The males perform an unusual mating display whereon they sing in flight with their legs dangling down. When Audubon illustrated this behavior, the editor removed one of the birds from the print because he thought it looked unrealistic!

Mongabay: How did your time at the University of Wisconsin—Stevens Point, prepare you to go on for a Masters and PhD?

Sarah Lehnen: The great thing about the wildlife program at Steven’s Point was their emphasis on field experience. The course work included a mandatory 6-week summer session where I worked with a team of other students on various projects, including conducting timber surveys, digging cores for soil samples, and trapping small mammals. Steven’s Point also had a very active student chapter of the wildlife society that had numerous ongoing projects. This balance of academics and hands-on experience made for a smooth segue into graduate school.

Mongabay: What advice would you give students interested in pursuing a career in biology and conservation?

Sarah Lehnen: Try to get an internship or volunteer at an institution whose work you admire. Ask a lot of questions, be persistent, and try to keep an open mind – opportunities don’t always present themselves in the forms we expect.

Mongabay: How important is field experience for applying to graduate school in biology? What advice would you give for students trying to find studies to participate in?

Sarah Lehnen: There are a glut of field positions offered in the summer, many of which are offered by graduate students. If you can’t find a paying position, some graduate students without the funds to hire workers will offer free board to volunteers. Field work can be tedious, repetitive, and unpleasant. I’ve met several people who liked the idea of field work better than the actual experience. My advice would just be to explore several options to find the best fit for your unique talents and interests.

SHOREBIRDS

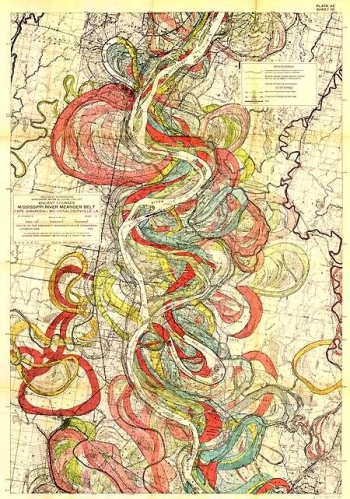

Mississippi River alluvial valley. Image by: Harold Fisk, 1944. Map of ancient courses of the Mississippi River, Cape Girardeau, MO – Donaldsonville, LA. |

Mongabay: You’re currently working in the lower Mississippi River alluvial valley. What is special about this ecosystem?

Sarah Lehnen: The Mississippi River Alluvial Valley represents the historic floodplain of the lower Mississippi River. The Mississippi River carved out the alluvial valley over many centuries as it meandered its way across the landscape. The area abounds with horseshoe-shaped lakes formed as the river changed its course. Here’s a map created by Fisk in 1944 of the historic pathways of the great Miss. As you can see, the path of the river has changed extensively over time.

One neat thing about the alluvial valley is that you can see it from space –the alluvial valley is much flatter and less forested than the surrounding regions and this change in landscape is pretty distinctive. Historically, the Mississippi River alluvial valley was a 24.7 million acre complex of forested wetlands interspersed with swamps, cypress-tupelo brakes, scrub-shrub wetlands, and emergent wetlands. This vast complex of wetlands provided a filtration system and provided habitat for numerous wildlife species. However, the landscape in the Mississippi River alluvial valley has changed dramatically during the last 200 years, with the most rapid changes occurring since the 1920s.

Today, only about 20 percent of the original forest remains in the MAV with the rest of the land converted to agricultural production. Although this isn’t good for wildlife dependent on forests it can be good for other species. Aquaculture (or fish farming), primarily for the production of catfish but also baitfish and crayfish, is a big industry in this region and these “working wetlands” provide habitat for numerous bird species including shorebirds. The highest number of shorebirds I’ve seen in any one location in the MAV has been on these farms with a couple of thousand shorebirds using one pond.

Mongabay: Many migrating shorebird species are in decline, but a study you did found that habitat in the Mississippi River valley was large enough to support their populations. Why do you think they are declining then?

Shorebirds congregating at a crayfish farm in Louisiana. Photo by: Sarah Lehnen. |

Sarah Lehnen: The U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan addresses the 53 shorebird species that breed in North America. Of these, it identifies 7 as “highly imperiled” and 21 as “species of high concern”. Most shorebird species that are found in the United States are migratory, travelling between their breeding areas in the arctic to their wintering grounds in Central and South American. The area where I worked in the lower Mississippi River Valley was historically (as in pre 1920s) forested. Shorebirds prefer open landscapes where they can see predators coming, so the Mississippi Alluvial Valley is actually better habitat for them now than it was historically. However, the Mississippi River Valley is only one part of their migratory route and shorebirds are still vulnerable to habitat loss along the remainder of their migratory pathways and on their breeding and wintering grounds.

Mongabay: How would changes in bird behavior make it look like the birds were declining when in fact their populations may be stable?

Sarah Lehnen: Because shorebirds are on the move most of the time, spending close to half their year on migration, it can be difficult to determine what is a true change in the number of birds versus a change in migratory behavior. For instance, fewer birds being observed at a migratory stopover site could be caused by a population decline of that species or by birds shortening the length of time they spend at that site, or by birds shifting to different sites.

Researchers have suggested that in British Columbia increased predation pressure caused by rebounding populations of peregrine falcons led to shifts in shorebird behavior. To reduce their chances of being eaten, shorebirds spent less time at stopover sites and avoided some of the larger coastal sites where they had typically congregated. However, the first thing researchers noticed was that fewer birds were being observed at some of the main sites. That said, many shorebird species are most likely in decline; this case merely illustrates the complexity of determining the root cause of a change in observed shorebird numbers. Habitat destruction, climate change, disease, increases in native and non-native predators, and changes in food supplies are thought to be responsible for the downward trends observed in shorebird populations throughout the world.

Mongabay: Does body size of birds affect how long they stay at stopover sites?

Pectoral Sandpiper caught in a researcher’s net. Photo by: Sarah Lehnen. |

Sarah Lehnen: There are many factors that affect how long a bird stays at a stopover site during migration. Weather can have a huge influence; a good tailwind can greatly reduce the energetic cost of flight so there is generally a lot of migratory activity during favorable wind conditions. The availability or perceived availability of habitat farther down the road can also influence decisions. Some birds have a “hopping” strategy where they stay at many sites for a brief period; other birds are “jumpers” where they stay at only a few sites but they stay at these sites for longer periods. Normally, birds load up on food during migration; in the bird world we regard a bird with a lot of fat as in being better condition to migrate than a lean bird. Because access to food during migration can be unpredictable, it pays to have a big gas tank, so to speak. Being heavier has a price in terms of speed and maneuverability though, so when predator numbers increase it may be better to stay lean.

Mongabay: What conservation efforts would you recommend to help these species?

Sarah Lehnen: Conservation of intercontinental migrants is difficult. One of the species I’ve worked with most, the pectoral sandpiper, breeds in the arctic of Canada and spends its non-breeding season in Argentina so there are a lot of jurisdictions crossed in a given year with a gauntlet of obstacles to overcome. In the U.S., approximately 50 percent of natural wetlands have been filled or drained and the U.S. continues to lose 24,000 acres (about 35 square miles) of natural wetlands per year. During fall migration, hunters in Barbados use semi-automatic weapons to hunt shorebirds as they move through, with as many as 30-45,000 shorebirds shot each year. In Argentina, solid waste dumped on beaches near Rio Grande and oil exploration using explosive charges in San Sebastian Bay threaten to destroy principal wintering habitat for shorebirds. What would benefit these species most is widespread international cooperation to insure protection of their habitat during all phases of their life histories.

Mongabay: Since the animals breed in the Arctic, how do you think climate change may be impacting them?

Sarah Lehnen: In some areas, they may respond by shifting their breeding areas farther north. There is also concern that coastal areas, which provide most of the habitat used by migrating shorebirds, will be inundated with water under a warming climate. Because of development and topography, it is unlikely that the amount of new habitat created will compensate for the amount of habitat lost.

Mongabay: How does studying migration patterns help with conservation efforts?

Top: The Red Knot (Calidris-canutus). Photo by: Jan van de Kam for PLoS ONE paper. Bottom: The Dunlin (Calidris alpina). |

Sarah Lehnen: For a species to have long-term population viability it needs to have the needs of all parts of its life history met. Species like Red Knots and Dunlin that concentrate in large numbers in a single area are especially vulnerable. Loss of a stopover area could mean the destruction of a whole flyway population of shorebirds. For example, the 30,000 Red Knots feeding on horseshoe crab eggs in Mispillion Harbor, Delaware Bay are highly vulnerable to human alteration of this resource, or even a catastrophic storm. The better knowledge we have on shorebird migratory patterns and needs, the more focused conservation efforts can be.

AVIAN FLU

Mongabay: Can you tell us about Avian Flu? How does it spread?

Sarah Lehnen: Wild birds are the natural reservoirs of influenza viruses that infect other vertebrates, including humans. During the last decade there have been an increasing number of human infections with influenza viruses that are typically associated with avian species. Of particular concern have been human infections from the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1. Although it is rare for an individual strain or subtype of avian influenza to infect more than one species, the lineages of H5N1 are unusual in the diversity of species they have infected worldwide. Infection of influenza in birds typically occurs following ingestion of the virus shed in feces. Virus-contaminated water likely serves as an important ‘‘vector’’ by facilitating fecal–oral transmission of avian influenza viruses in wild birds associated with water, which is why shorebirds and waterfowl are considered to be at high risk for transmitting the virus.

Mongabay: Why is the US government concerned about these species in this particular area?

Sarah Lehnen: Several migratory shorebirds with Alaskan and Siberian breeding grounds share habitat with Asian species during the breeding season before returning to their non-breeding habitats in North and South America. This contact raises concerns that these birds will serve as disease vectors to bring H5N1 to North America. However, the frequency of transmission of the avian influenza among wild avian species is still unclear. Some studies suggested that transmission rates are low among wild birds; others suggest that avian influenza can readily infect multiple bird species if the birds share the same breeding and/or feeding areas.

Mongabay: Have any of the species you tested come up positive for H5N1?

Sarah Lehnen: No, fortunately. H5N1 still has not been detected in North America although other subtypes of the influenza virus have been found in shorebirds and waterfowl.

THE FUTURE FOR BIRDS

Mongabay: Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, said in March of this year that one in three birds are endangered in the United States. The US has a long history of conservation, so how do you think the country has reached such a problematic place for birds?

Male brown-headed cowbird. Photo by: Jan Malik. |

Sarah Lehnen: If you think of all the requirements that a bird has over the course of one year: appropriate breeding habitat, safe migratory routes, quality wintering habitat, damage to any one of these components can cause the population to go into decline. Habitat changes and loss can result in reduced reproductive success.

For example, the Brown-headed Cowbird is a nest parasite; rather than raise its own young it lays its eggs in the nests of other species. The cowbird used to be restricted to open short-grass prairies of the Midwestern United States but fragmentation of forest habitat led the cowbird to expand its range to the west and east, giving it exposure to species that had never evolved any defense to its parasitic habits. These newly parasitized species of birds put increasing effort into raising the cowbird young at the expense of their own offspring.

In addition, there are a wide variety of causes of direct mortality to birds, from pesticides, the spread of free-roaming cats, and the proliferation of communication towers, buildings, and wind mills with which migrant birds collide. In addition to all the problems they encounter in the United States, these birds face another suite of problems once they cross over political boundaries on their migration routes. It’s a dangerous world out there these days for birds. In my humble opinion, even with all the other problems we face as a nation and as a society, we have obligation to ensure that our children inherit as diverse and fascinating a world as we have now. Every species that we lose we lose forever.

Mongabay: How can people help birds in their region?

Sarah Lehnen: A few simple things can help birds a great deal. If you have a pet cat, keep it indoors. Indoor cats live twice as long on average as outdoor cats and scientists estimate that domestic cats kill millions of birds each year. Make your backyard wildlife friendly by planting native trees and shrubs and discouraging neighborhood cats. Also, please support legislation that benefits birds and other wildlife. The American Bird Conservancy (abcbirds.org) has information about current legislation relevant to birds. Some simple things, like switching from steady-burning to strobe lights on communication towers, could save millions of birds without compromising aviation safety but the Federal Communications Commission won’t change its regulations until enough attention is drawn to the issue.

Mongabay: What’s next for you?

Sarah Lehnen: The future is unwritten. I have many ideas but I try to remain open to new opportunities as well.

A wide variety of shore birds at crayfish farm in Louisiana. Photo by: Sarah Lehnen.

Close-up of one of Lehnen’s favorite birds: the yellow-breasted chat. Photo by: Sarah Lehnen.

Related articles

Vlad the Impaler of the bird world now at Bronx Zoo: skewers prey on thorns and barbed wire

(09/15/2009) The loggerhead shrike, also known as the ‘butcher bird’, employs a feeding strategy that would have been right at home in 15th Century Transylvania. Like the infamous Vlad the Impaler (the brutal prince which Bram Stoker based Dracula off), the loggerhead shrike is truly skilled at impaling. Using its hooked beak to break the spines of insects, lizards, rodents, and even other birds it then impales them on thorns or barbed wire to hold them while it disembodies them. Now, the Wildlife Conservation Society’s (WCS) Bronx Zoo has brought the loggerhead shrike into its collection, but the shrike is there to illustrate more than its unique feeding practices.

Priorities in global bird conservation ‘misplaced’

(08/10/2009) Bird conservation is misplacing its priorities by focusing on non-threatened bird species in developed countries, rather than threatened species from tropical nations, report researchers writing in Tropical Conservation Science.

Birdwatching contributes $36 billion annually to U.S. economy

(07/15/2009) One fifth of Americans are birdwatchers, according to a report released today by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

New glass could reduce one billion annual bird deaths from U.S. window collisions

(07/13/2009) The deaths of billions of birds annually due to collision with window glass can be reduced through simple measures including dimming lights in buildings at night, landscaping changes, and using window coverings that make glass more visible to birds, reports a bird expert writing in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. Conducting experiment with different types of firm on plastics and glass, Daniel Klem Jr., an ornithologist at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, found coverings that create visual “noise” can dramatically reduce bird-window collisions without drastically increasing costs or impeding visibility for humans relative to conventional glass. The most effective covering was a new exterior film with evenly spaced ultraviolet (UV)-reflecting and UV-absorbing patterns, which can be seen by birds but not humans.

Updated Red-List: 192 birds are Critically-Endangered

(05/14/2009) In this year’s updated IUCN Red List on birds, six species were down-listed from Critically Endangered to Endangered, but eight species were up-listed to Critically Endangered, leading to the highest number of Critically Endangered birds ever on the list. In all 1,227 bird species (12 percent) are currently considered threatened with global extinction.

Bird migrations lengthen due to global warming, threatening species

(04/15/2009) Global warming is likely to increase the length of bird migrations, some of which already extend thousands of miles. The increased distance could imperil certain species, as it would require more energy reserves than may be available. The new study, published in the Journal of Biogeography, studied the migration patterns of European Sylvia warblers from Africa to breeding grounds in Europe every spring. They discovered that climate change would likely push the breeding ranges of birds north, causing migrations to lengthen, in some cases by a total of 250 miles.

One third of US birds endangered

(03/19/2009) Ken Salazar, the nation’s new Secretary of the Interior, today released the first comprehensive report on bird populations in the United States. The findings are not encouraging: nearly one third of United States’ 800 bird species are endangered with even once common species showing precipitous declines. Habitat loss and invasive species are blamed as the largest contributors to bird declines.

Fit with tiny backpacks, songbirds reveal speed of migration at 311 miles a day

(02/12/2009) Using extra tiny geo-locator backpacks, researchers have tracked songbirds’ seasonal migrations for the first time, according to research published in Science . The researchers discovered that these beloved birds fly faster and further than anyone ever imagined. The data taken from the geo-locators surprised everyone. Stutchbury and her team discovered that during their migrations between Pennsylvania and South America songbirds flew more than 311 miles a day, three times higher than previous estimates.

Global warming drives birds north

(02/11/2009) Nearly 60 percent of the 305 species found in North America in winter have shifted their ranges northward by an average of 35 miles, according to an assessment by the Audubon Society.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service program restores bird habitat on farms and ranches

(10/28/2008) Matt Filsinger is driving his white pickup headed northeast from Sterling to look at two of his projects. This self-described introvert speaks enthusiastically about his job. “Ducks, ducks, ducks – that’s what I love!” says Filsinger, grinning broadly. Filsinger is a wildlife biologist with the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He works with private landowners to set aside land and create attractive habitat for imperiled species. Specifically, he designs wetlands to attract waterfowl. Partners for Fish and Wildlife is a successful program that has been around since 1987. Landowners, including farmers and ranchers, form partnerships with the program because they reap a variety of benefits from it. Nonprofit organizations such as Ducks Unlimited, Audubon and the Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory are also partners. Collaboration between the federal government and private landowners is essential to preserving habitat and species, as 73 percent of the country’s land is privately owned, and most wildlife lives on that land.

Migratory waterbird populations in decline in Europe

(09/15/2008) 41 percent of 522 migratory waterbird populations on the routes across Africa and Eurasia show decreasing trends, reports a new study released at the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement meeting in Antananarivo, Madagascar.

Birds face higher risk of extinction than conventionally thought

(07/14/2008) Birds may face higher risk of extinction than conventionally thought, says a bird ecology and conservation expert from Stanford University. Dr. Cagan H. Sekercioglu, a senior research scientist at Stanford and head of the world’s largest tropical bird radio tracking project, estimates that 15 percent of world’s 10,000 bird species will go extinct or be committed to extinction by 2100 if necessary conservation measures are not taken. While birds are one of the least threatened of any major group of organisms, Sekercioglu believes that worst-case climate change, habitat loss, and other factors could conspire to double this proportion by the end of the century. As dire as this sounds, Sekercioglu says that many threatened birds are rarer than we think and nearly 80 percent of land birds predicted to go extinct from climate change are not currently considered threatened with extinction, suggesting that species loss may be far worse than previously imagined. At particular risk are marine species and specialists in mountain habitats.