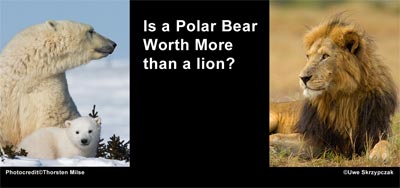

For most environmentalists and animal rights activists it is an almost blasphemous idea to compare the value of one species with that of another, especially when that value is measured in terms of marketing potential for climate change awareness.

In recent years, broad media coverage has turned the polar bear into a global symbol for the effects of climate change not only in the Arctic, but in the rest of the world too. In Germany particularly, the birth and highly publicized early life of the polar bear “Knut” at the Berlin City Zoo has intensified this symbolic effect. The fact that the Arctic ice is melting due to global warming is an established fact, and environmentalists the world over are lucky to have the polar bear and its disappearing habitat as a symbol for the global effects of pollution. All this publicity has, however, spread the exaggerated idea that polar bears are already on the verge of extinction.

|

Between 20,000 and 25,000 polar bears are known to live in the Arctic, and there are almost certainly several thousand more living in more remote areas. Polar bears are, in evolutionary terms, the youngest predators on Earth, and many scientists think that they are not good at adapting to climatic change. But polar bears have already survived a period of intense global warming in the Middle Ages, when Greenland was partially ice-free and served as Viking farmland. Evolution then helped the polar bear to reduce its body weight by about 20 percent in the course of just a few decades, leading me to doubt the theory that polar bears cannot adapt quickly enough to survive.

Polar bears are without doubt wonderful creatures whose existence is-like most other large animals on our planet-clearly threatened. But what is happening to their greatest rival for public attention and charitable money: the lion – king of the jungle?

We have all seen documentary films with clever edits that turn one lion into a whole pride, and Hollywood likes to show troops of hungry and dangerous-looking lions on the prowl. But in many parts of East Africa even the best movie tricks don’t help, as there simply aren’t any lions left to film.

Worldwide, there are only about 20,000 lions surviving in the wild.

In spite of conclusive evidence from the well-known lion specialist Craig Packer that shooting young male lions accelerates the demise of the species, many African countries still allow commercial hunting as a way of attracting badly needed hard currency.

Kenya used to have one of the largest wildlife populations in the world but, in spite of a general ban on hunting, the number of animals-including lions-has decreased by as much as 75 percent in recent years.

Photo by Uwe Skrzypczak |

Climatic change is already having catastrophic effects in many parts of East Africa. For decades now, the weather phenomenon known as El Niño has produced anti-cyclic wet and dry seasons that directly affect the migratory patterns of the great herds of African ungulates-the most important source of food for the region’s predators. Decreasing precipitation and years of drought have caused a full-blown catastrophe in Kenya. Increasingly arid farmland and large-scale cultivation of cut flowers and tropical fruit for export have led to lakes and entire river systems running dry. The indigenous people often don’t have sufficient knowledge to employ efficient crop rotation and often ruin their own land. Profit-hungry land owners exacerbate the problem with huge monoculture plantations. The region’s wildlife has increasingly little space to live, and is often forced to share its habitat with domesticated farm animals. There are now only about 2,000 lions left in the whole of Kenya, and every year 100 more disappear. If this trend continues, inbreeding will put an end to genetic variety in the lion population and it is estimated that within 15 years, the only lions in Kenya will be living in zoos.

Others say that the intact gene pools of neighboring Tanzania’s 3,000 lions and 2 million ungulates will help preserve the balance. These theories assume that lions and other wildlife will migrate from Tanzania back to Kenya, but unfortunately overlook the fact that large parts of the ecosystem of the northern Serengeti (the Mara) lie within Kenya.

The Mara River is the North Serengeti’s lifeline but has recently lost almost 40 percent of its water due to deforestation of the Mau forest in its upper reaches and excessive agricultural irrigation elsewhere. If the river’s water level sinks by more than half, the Mara ecosystem will simply collapse. For three months of the dry season, this area is a major source of food for the region’s ungulate herds during their migration to the Masai Mara.

If the Mara ecosystem should collapse, the resulting food shortfall would have a serious effect on the ecosystem of the entire Serengeti, with scientists estimating a short-term decrease in the ungulate population of between 75 and 90 percent.

This would-at least temporarily-upset the rules of natural population control which prevent predators from hunting their prey to extinction.

The Serengeti’s 10,000 lions, leopards, and hyenas would then decimate the remaining ungulate population, resulting in extinction for the predators themselves. Lions are territorial hunters and would therefore be the first to go.

Photo by Uwe Skrzypczak |

This threat scenario is more acute than the slow melting of the Arctic ice, and the Mara’s food supply has this year already reached the brink of collapse. Due to continuing drought in Kenya, the rain in the Tanzanian Masai Mara only came at the end of the dry season, leaving too little fresh grass to feed the migrating ungulate herds. Fortuantely, anticyclic rainfall in the Western Corridor and the north-eastern Serengeti provided the gnus, zebras and gazelles with enough to eat, and helped them to narrowly avoid massed starvation. The herds were able to graze for longer and to continue their migration safely, and the Masai Mara-an important tourist destination-just avoided becoming an enormous animal graveyard. The region’s predators were lucky this time and were able to eat their fill. But it is only a matter of time before they once again start to prey on Masai livestock.

The Masai have recently taken to using bait doused with Carbofuran (a highly toxic pesticide) to protect their stock from predators, and the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) recently reported 10 fresh lion deaths by poisoning.

If things are to change, the problems facing the Serengeti, the Masai Mara, and the rest of the East African environment have to gain significant public attention, and the lion has to become a symbol for the survival of the African environment the same way the polar bear symbolizes the plight of the Arctic.

East Africa is heavily dependent on income from safari tourism, and protection of the region’s wildlife contributes not only to active environmental protection, but also plays a significant role in the region’s aid programs.

You too can help by supporting groups like the WildlifeDirect, which provides direct funding to conservationists working in the field.

Uwe Skrzypczak is a wildlife photographer. If you are interested in helping him increase long-term awareness of the problems facing the Mara region, you can contact him at serengeti-wildlife.com