Saving the Ethiopian wolf in face of habitat loss, diseased dogs, and climate change, an interview with Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, founder of the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme.

Living on the roof of Africa, the Ethiopian wolf is one of the world’s rarest carnivores, if not the rarest! Trapped on a few mountain islands rising over 4,000 meters above sea level on either/both sides of the Great Rift Valley, this unique canid has so far survived millennia of human-animal interactions in one of Africa’s most densely populated rural lands. But the threat of climate change and a shifting agriculture frontier may require new conservation measures, according to Argentine-born Claudio Sillero, the world’s foremost expert on the Ethiopian wolf, who has spent two decades championing this rare species.

Claudio Sillero releasing a vaccinated and tagged wolf, Morebawa, Bale. ©Graham Hemson  Ethiopian Wolves. ©A.L. Harrington. |

“I first heard of Bale Mountains of southern Ethiopia in 1987, over dinner with friends in a farmhouse near Naivasha. The New York Zoological Society was looking for someone to study the Abyssinian wolf or Simien fox (as it was known then), a mysterious carnivore found only in a few Ethiopian mountains. That night I rushed to my carnivore books to learn more about this enigmatic animal and, less than ten days later, I was in a plane bound for Bale,” Claudio Sillero told Mongabay.com.

In 1995, Dr Sillero founded the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme (EWCP). The organization works with both the Ethiopian government and local communities to protect the wolf and other highland species.

“By and large the people that live in the Ethiopian highlands are relatively tolerant of wildlife, but their priority is one of survival, and unless their livelihoods can be brought into line with sustainable practices, the meadows and moors they need to graze their cattle, gather firewood and tend their crops will soon be all degraded to bare rock,” Sillero says, describing the difficult position that Ethiopian locals find themselves in. One of the biggest impacts the local population has on the wolves is their increasing tendency to raise domestic dogs.

“Domestic dogs not only compete for food, chase them, and transmit rabies and canine distemper to their wild cousins, but may even hybridize with them,” Sillero says calling domestic dogs the most “real and immediate threat to wolves”.

To address this concern, the EWCP has worked long and hard to eliminate potentially dangerous contact between dogs and wolves, including giving rabies vaccines to over 60,000 dogs. Conservationists are also working to ban dogs within the National Park.

Claudio Sillero |

However, another creeping threat proves far less tangible: climate change.

“With the Horn of Africa, and most of globe for that matter, steadily warming up since the end of the Pleistocene, the Afroalpine grasslands and moors home to the wolves continue to shrink, rendering their specialists’ success into an ecological trap,” Sillero says. He hopes that translocating wolves between populations—thereby preventing local extinctions and maintaining genetic diversity—may be able to save the species from extinction even in a warmer world. However, he says that he expects “local extinctions for some montane specialists”.

Still, Sillero sees optimism and hope as essential to a career in conservation. He says that we must resist “the notion that it is too late to stop the humankind’s juggernaut destroying our wonderful biosphere. Against the odds, we should continue to work and campaign for a change in the current trends of biodiversity loss, and secure a future, at least for some of this grandeur of life, not just for us, but for generations to come.”

In a November 2009 interview Mongabay spoke with Dr Claudio Sillero about the ecology of the Ethiopian wolf, its relationship with locals, and the myriad threats facing this rare canid.

AN INTERVIEW WITH CLAUDIO SILLERO

Mongabay: What is your background and how did you end up working in Africa?

Claudio Sillero |

Claudio Sillero:

I was born in a small town in the Argentine pampas, and grew up between the town, where I attended school, and my grand-father Emilio’s estancia. I learnt the farming craft from my granddad and the farm hands or “gauchos”, and spent long days riding, herding cattle and sheep and farming wheat. A keen naturalist, my early hunting interest slowly gave way to more conservationist feelings. With my brother I kept and bred all sorts of pets, including snakes, tortoises, starlings, rheas, armadillos and opossums. Summers were spent fishing, collecting lizards in the dunes of the nearby Atlantic shores, or in family trips camping, fly-fishing and trekking in the Patagonia and the Andes. I can’t pin it down to any specific event, other than watching many episodes of the 1960s TV series “Daktari,” but at some point in those early days I started hatching a plan that one day I would go to Africa to work with wildlife.

I had a last-minute change of mind and instead of becoming a vet I read Zoology at the University of La Plata, spiced with summer projects in remote parts of the country, watching foxes, otters and searching for the elusive jaguareté. My African plan came one step closer when in 1985 an application to study in Nairobi University was successful, and aged 24 I found myself in East Africa establishing a long cherished field project studying the impact of spotted hyaenas on endangered black rhinos in the mountain forests of the Aberdare National Park.

Mongabay: How did you get interested in Ethiopian wolves?

Claudio Sillero. Courtesy of EWCP. |

Claudio Sillero:

I first heard of Bale Mountains of southern Ethiopia over dinner with friends in a farmhouse near Naivasha. The New York Zoological Society was looking for someone to study the Abyssinian wolf or Simien fox (as it was known then), a mysterious carnivore found only in a few Ethiopian mountains. That night I rushed to my carnivore books to learn more about this enigmatic animal and, less than ten days later, I was in a plane bound for Bale. Four years studying the biology of Ethiopian wolves in the freezing heathlands of Bale (little did I know that I would end up so much higher and colder than in the African plains of my dreams…) resulted in masses of information, many publications, and recommendations to the Ethiopian government stressing the dire situation of the Ethiopian wolf, now officially recognized as rarest, and one of the most endangered carnivores in the world. Over 4,000 hours of detailed observations on the ecology and behavior of 130 individually recognized wolves led to a doctorate from the led to a doctorate from the WildCRU at the University of Oxford and sowed the seeds for the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme.

I founded the EWCP in 1995 to work closely with the Ethiopian authorities and the local community to protect the highlands unique wildlife. Our long-term view is only possible thanks to the continued support of our fiends at the Born Free Foundation and the Wildlife Conservation Network.

While my job at Oxford involves many other projects and responsibilities I continue to stick to my aspiration of securing the survival of Ethiopian wolves and other Afroalpine wildlife for many years to come.

Vaccination team, Morebawa in the Bale Mountains. ©Graham Hemson |

Mongabay: Why are Ethiopian wolves endangered and what are presently the greatest threats to them?

Claudio Sillero:

Whilst most members of the Canid family are versatile and opportunistic – the wily coyote a superlative example of these traits – Ethiopian wolves are highly specialized to life in the “roof of Africa”. Those qualities that made them successful in an expanding ecosystem during the Pleistocene (where their ancestors arrived in Africa from Eurasia), have ironically resulted in their current plight. Only a handful of mountain enclaves in the highlands of Ethiopia now harbor the right conditions, and ample rodent prey, to support viable populations of Ethiopian wolves. Less than 500 adult wolves survive in half a dozen mountain ranges, and most of these populations are tiny.

Pups and dominant female from Meggity pack. Courtesy of EWCP. |

With the Horn of Africa, and most of globe for that matter, steadily warming up since the end of the Pleistocene, the Afroalpine grasslands and moors home to the wolves continue to shrink, rendering their specialists’ success into an ecological trap. Changes in temperature and rainfall operate in a time scale that will influence population dynamics and even extinctions. But faster changes occurring within our lifespan, such as agriculture encroachment and soil erosion, are also bringing rare species to the brink.

Mongabay: How are other endemic species in the Ethiopian highlands faring?

Claudio Sillero:

Ethiopia is the cradle of humanity, and farming has been modifying its surface for millennia. Expanding populations and the need for arable land bring about an incessant pressure on natural habitats. Barley crops and potato fields are slowly encroaching the last relicts of Afroalpine diversity, and other highland endemics such as the stubborn walia ibex, the graceful mountain nyala, the svelte wattle crane, down to the gopher-like giant molerat, are all seeing their habitat shrink and bringing local extinction a step closer.

Mongabay: How do you encourage local people to protect a species that they may see as a pest or a threat to their livestock?

Vet officer explaining about the risk of rabies during a dog vaccination campaign. Courtesy of EWCP. |

Claudio Sillero:

By and large the people that live in the Ethiopian highlands are relatively tolerant of wildlife, but their priority is one of survival, and unless their livelihoods can be brought into line with sustainable practices, the meadows and moors they need to graze their cattle, gather firewood and tend their crops will soon be all degraded to bare rock. A long-term view to help these poor rural communities find a sustainable livelihood has to take into account the serious environmental cul-de-sac they find themselves in. Without bringing conservation into the model there’ll be no future for either.

Mongabay: Interaction with domestic dogs is an important vector for disease transmission for Ethiopian wolves. How are you convincing local people to reduce the number of dogs they keep? Will this have favorable impacts on other wild species as well?

Claudio Sillero:

Wherever man goes, their domestic animals follow. And while many highland wildlife species have been able to coexist with highland shepherds and their livestock, domestic dogs bring in an additional challenge for Ethiopian wolves. Dogs pose the most real and immediate threat to wolves. They not only compete for food, chase them, and transmit rabies and canine distemper to their wild cousins, but may even hybridize with them.

Ethiopian Wolf pups. Courtesy of EWCP. |

As such we have recognized that we cannot deliver in our goal to protect these rare carnivores unless we make dogs central to our strategy. We have been working with people in the Bale Mountains to address this conflict, and to date we have vaccinated in excess of 60,000 dogs to prevent rabies getting across to wolves. Our long-term view is that within the National Park there should be no domestic dogs, and we are working hard to deliver on that objective. But in the meantime our vaccination work brings us closer to the local communities and provides a channel of communication to transmit our environmental education message.

People still need dogs to protect their animals from hyenas, although our studies show that dogs are not very efficient at doing their job! There is more that we can do to improve the night protection for people’s livestock, thus reducing their dependence on guarding dogs and in time reducing the negative impact of dogs on wild carnivores.

Mongabay: Are they receptive to your efforts? More generally, how can conservationists work better with local populations to ensure that wildlife preservation doesn’t conflict with the needs of local communities?

Claudio Sillero:

It is a long-term game, and only through committed efforts and dedication the necessary trust and common ground between the needs of people and wildlife can be found.

Mongabay: Have there been any studies to gauge whether wolves and other species in the Ethiopian highlands will be adaptable to climate shifts?

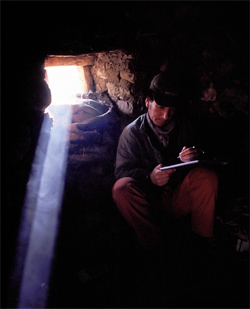

Field monitor from Dinsho, Bale. Courtesy of EWCP. |

Claudio Sillero:

We are currently working on this very question. Climate shifts in mountain ranges tend to impact on specialists, and there are few mitigation approaches available to protect small populations that get caught in this habitat vortex. So expect local extinctions for some montane specialists, although for wolves and other large mammal species the metapopulation management paradigm will become part of the solution, whereby isolated populations are treated as part of a single, “meta”, population by translocating animals between them and enabling recovery and genetic flux. Expect more of these interventions in decades to come.

Mongabay: How can people in places like the U.S. help conservation in the Ethiopian highlands?

Claudio Sillero:

Of course the chief need is funding! But in the long-term the most important impact will come from a major shift of attitude toward environmental conservation at government level. We live in a global world, and some of the decisions that will determine whether the highlands of Ethiopia, or any other shrinking hotspot for that matter, will persist, are determined by the willingness of the richer nations to promote conservation, sustainable development and an honest system to recognize and pay for ecosystem services. So please keep writing to your congressmen!! Promoting alternative livelihoods will also help, and trekking tourism is a concrete low-impact activity that may help us protect some of these Afroalpine enclaves.

Mongabay: Do you have any tips for aspiring field conservationists?

Courtesy of EWCP. |

Claudio Sillero:

My own journey from the Argentine wheat belt to Oxford via the roof of Africa, and a career in conservation encompassing projects in four continents, is a good example that dreams can come true. Often it is not so much careful planning that will get you there, but the conviction that we can all make a difference, in one way or other. Helping out with a local project, developing an interest in the outdoors, securing a good university degree, volunteering for established programs, will surely help you along the way. But foremost, in my view, is nurturing a closeness with nature, and resisting the notion that it is too late to stop the humankind’s juggernaut destroying our wonderful biosphere. Against the odds, we should continue to work and campaign for a change in the current trends of biodiversity loss, and secure a future, at least for some of this grandeur of life, not just for us, but for generations to come.

Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme