Playful giant river otters, massive anacondas, unafraid tapirs, and the world’s largest spider recorded in Guyana’s lost world.

An expedition deep into Guyana’s rainforest interior to find the endangered giant river otter—and collect their scat for genetic analysis—uncovered much more than even this endangered charismatic species.

“Visiting the Rewa Head felt like we were walking in the footsteps of Wallace and Bates, seeing South America with its natural density of wild animals as it would have appeared 150 years ago,” expedition member Robert Pickles said to Mongabay.com.

A PhD student with the University of Kent and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), Pickles is currently studying the genetics of the giant river otter in hopes to save this species from habitat loss. While the expedition, which also included tapir expert Niall McCann and local naturalist and tour operator Ashley Holland, found the necessary scat-samples that Pickles sought, they also took data on the biodiversity of one of the Guyana’s Shield’s most untouched regions hoping to draw attention to a little-known area threatened by big logging and oil companies.

Robert Pickles holding a red fire snake (Chironius scurrulus). Photo courtesy of Robert Pickles. |

In just six weeks the expedition recorded an astounding variety of life: 158 species of birds, 22 species of medium to large mammals, and half of Guyana’s known endangered species. “Including,” Pickles says, “all the felids with several captures of puma in the camera traps, the presence of the mighty Harpy and crested eagles, the extremely elusive bush dog, abundant tapir and then just below the Falls is an important breeding ground for the giant South American river turtle.”

Due to the difficulty of reaching Rewa Head, the ecosystem was been little touched by past or present hunters, leaving the animals largely unafraid of Pickles and other expedition members.

“It was quite remarkable the number of game species such as paca and currassow that could be seen and approached with ease. We also encountered four tapir during the expedition […] they were entirely nonchalant about our presence and would quite placidly paddle just next to the boat as we drifted downstream,” he says.

Most surprising, according to Pickles, was the number—and size—of the world’s largest snake found by the expedition in Rewa Head.

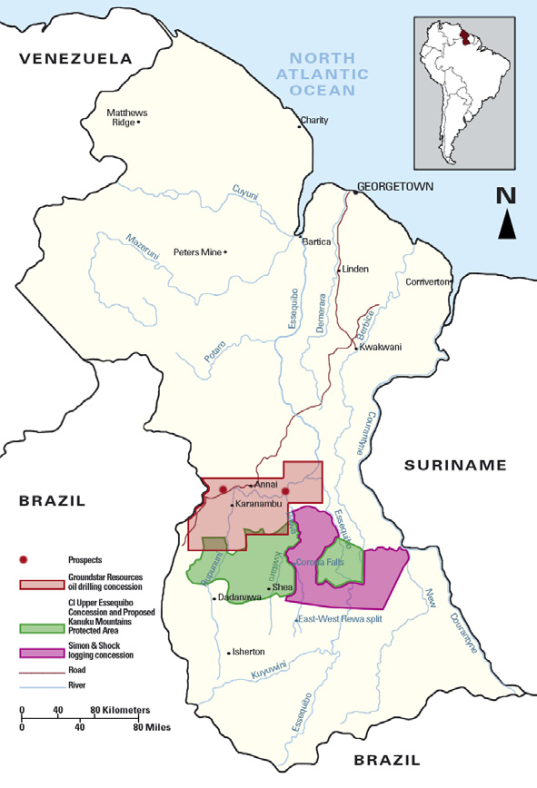

Location of the Rewa Head and extent surveyed by this expedition in red. Map courtesy of Robert Pickles. |

“I really have to say something about the anacondas up there though. We encountered 6 during our expedition, four of which were estimated as being over 16 feet. To verify our size estimates we caught a large snake basking on the river bank and measured her length with a rope. She turned out to be 18 feet 2 inches in length with a maximum girth of 27 inches. It was quite incredible to see so many very large snakes. Why do they get so large here whereas in the Venezuelan Llanos they rarely record them over 16 feet?” Pickles said, perhaps describing a future research project for an intrepid herpetologist.

This pristine wilderness—still free from the impacts of the modern world—may not remain so for long. Both a massive logging concession and an even larger oil drilling concession overlap the wilderness.

US-owned company, Simon and Shock International, currently has a license to extract timber from 400,000 hectares.

“The company has stated its environmental principles and has listed a range of measures to mitigate degradation of the concession,” Pickles says. “But the unfortunate fact is that no matter how green your intentions are, it can be very difficult to prevent the creep of hunting into a forest once you’ve put a road in there.”

The oil-drilling concession, covering an astounding 78 million hectares, poses similar threats according to Pickles.

“Drilling has yet to begin though the company has been prospecting around the village of Rewa. The concern with this is that environmental safeguards are put in place and stringently adhered to. Oil extraction can be achieved with minimal environmental impact provided the company is diligent, but there is also concern as to whether the development of roads will lead to hunting encroachment above Corona Falls,” he says, adding that indigenous groups in the area see these future developments as a mixed blessing, providing possible jobs on the one hand but encroachment on their lands on the other.

Camera trap photos from the expedition caught a large number of species, including the tayra Eira Barbara from the weasel family (above) and the ocelot Leopardus pardalis (below). Photos by: Rob Pickles, Niall McCann, Ashley Holland. |

Pickles says that the situation facing Rewa Head provides a perfect example of why the REDD program (Reducing Emissions through Deforestation and Forest Degradation) should be employed even in countries where currently deforestation rates are relatively low and forest cover remains high.

“While it is obviously extremely important to tackle deforestation in the frontline countries where this threat is occurring, which is what REDD initially set out to do, it is equally as important that nations with large tracts of pristine forest and a less severe deforestation threat do not get marginalized, but receive due recompense for not taking the ‘economically rational’ path and fully exploiting those natural resources,” explains Pickles. “Guyana is in an incredibly fortunate position in that it still retains 76 percent of its forest cover which constitutes some of the most carbon-rich forests of South America. As such, and with a president keen to offer his nation’s forests as part of the world’s carbon sink, Guyana should be embraced by the international community.”

If the Guyana forests are not valued by the wider-world they will likely be lost, and Rewa Head, an ecosystem that time forgot, will vanish along with all of its richness.

Employing the concept of ‘shifting baselines’—where humans lose their knowledge of a healthy ecosystem through generations of degradation and destruction—Pickles says that Rewa Head, with its abundant wildlife and incredible biodiversity, has the capacity to teach us what all of the Amazon was once like, if only we make the effort to save it.

“We forget what ‘natural’ and ‘pristine’ really mean and now think of places like the Rewa Head as being exceptional,” Pickles explains. “Whereas in reality this would have been the state of much of tropical South America, but the degradation has been going on for so long now that we are in danger of forgetting what it is supposed to be like.”

In a November 2009 interview Mongabay spoke with Robert Pickles about his six-week expedition to Rewa Head in Guyana, including the status of the giant river otter in the area, the abundance and diversity of other species, the threat of development to Rewa Head, and the possibility of saving this pristine place.

INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT PICKLES

THE GIANT RIVER OTTER

Mongabay: What is your background?

Robert Pickles: I did my undergraduate degree in zoology at the University of Bristol before working for 5 months as an Research Assistant on the Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) Skeleton Coast Jackal Project. Following that I put together a PhD proposal for a genetic study on giant otters, did a pilot study, received National Environmental Research Council funding and began the PhD in October 2006.

The photo shows an “inquisitive adult male giant otter approaching the boat. While some individuals are remarkably fearless and will approach to within several yards of the boat, the mood of the group is determined by the breeding female. If she feels threatened the group will normally ‘periscope’ and disappear,” according to Biodiversity Report on Rewa Head. Photo by Rob Pickles. |

Mongabay: What led to your interest in the giant river otter?

Robert Pickles: Back in 2003 my friend Niall McCann came up with the idea of an expedition to locate remnant populations of giant otters in Bolivia. A team of four of us received funding from the Royal Geographic Society and worked with the Bolivian NGO FaunAgua, spending two months exploring the rivers and streams in the east of the country, recording several new populations.

When you first encounter a pack of giant otters mid-river it’s a spine-tingling experience. In my case we’d just been piranha fishing and were rounding a bend in the river when we suddenly came across a pair traveling towards us. They immediately dived, then reappeared craning their necks out of the water like periscopes, working themselves downwind of us then, catching our scent, they let out a cacophony of snorts and wail screams which reverberated off the gallery forest walls before disappearing leaving their impression etched in my brain.

This bold animal, highly territorial yet with an infinite capacity for play is a fascinating species. It split away from the rest of the otters very early on in the tribe’s evolution and is remarkable for its sociality, with a high level of alloparental [parental care provided by a non-parent] care being shown by offspring from the previous year as well as unrelated immigrants to the pack.

Mongabay: What is the focus of your current study on the giant river otter?

“Territorial display by a group of giant otters above Corona Falls. Termed ‘periscoping’ the behaviour is accompanied by a cacophony of wails and snorts often backed up by a mock charge. For the biologist, periscoping allows pictures to be taken of the unique throat patterns allowing identification of individuals,” according to Biodiversity Report on Rewa Head. Photo by Niall McCann. |

Robert Pickles: For an endangered species, we really don’t know a huge amount about the giant otter. My research is in genetics and involves looking into the way the populations are structured throughout the range, where gene flow occurs and where populations have diverged through isolation. It aims to locate seats of genetic diversity and determine what effect the pelt hunting of the last century has had on that diversity. Understanding this, the phylogeography, will put us in a much better position for making informed decisions as to where best to allocate resources for conservation.

Mongabay: What are the threats to the giant river otter?

Robert Pickles: Currently the greatest threat to the giant otter is habitat degradation. As Amazonia gets opened up, so river traffic, pollution and conflict with fishermen all work against the recovery of the species.

Then of course there is climate change. A case in point might well become the otters of the Pantanal. Predictions are that this region will receive much less rainfall in the coming decades which will lead to a reduction in available habitat as well as prey for the giant otter. If you couple this with the Hidrovia plans then things get even worse. Hidrovia is the idea of making the Rio Paraguay navigable from Bolivia down to the Atlantic to allow cattle ranchers access to a lucrative market during the dry season. To this end plans are afoot to dredge, dynamite and straighten the river to allow the passage of ocean going tankers. It’s been predicted that this will lead to an overall drop in the depth of the Paraguay, which could in turn lead to up to a 25 percent decrease in the area of the Pantanal wetlands. When this combines with climate change, the two threats will act synergistically to cause terrific degradation to the wetlands.

EXPEDITION TO REWA HEAD IN GUYANA

Mongabay: What led to the decision to do an expedition to the Rewa Head area of Guyana?

Giant anteater Mymecophaga tridactyla on camera trap photo in Rewa Head. The giant anteater is classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Rob Pickles, Niall McCann, Ashley Holland. |

Robert Pickles: The idea for a biodiversity survey of the Rewa Head really spun off my need for giant otter genetic samples from across the species’ range. This region was recommended as one where I could be guaranteed of collecting samples, but it wasn’t until I had begun planning the trip with Niall and Ashley Holland that we realized that there was a lot more we could do up there in six weeks than just collect spraints [i.e. otter dung]. Hearing stories about the wealth of wildlife that could be found above the falls made us decide to take some equipment out and conduct some basic survey work simply to document what was there.

Mongabay: How are giant river otters faring in Rewa Head?

Robert Pickles: The Rewa Head is cut off from the Lower Rewa by waterfalls. Corona Falls have acted as a portcullis so that few have bothered making the arduous haul above, and once you do get above Corona there is a further string of cataracts and falls that require portaging. Consequently the old fur hunters never made it that far, leaving an enclave from which the giant otter has subsequently expanded. The population there is healthy; we recorded at a density of one pack every 13 miles, with a total population estimate of 35 animals. Although we didn’t spend time searching the Lower Rewa for otters, we did come across 4 groups and it seems likely that the population is recovering here.

Mongabay: What other species did the expedition uncover?

Niall McCann, Ash Holland, and the team measuring an anaconda Eunectes murinus from Rewa Head. Total length was determined as 18 feet 2 inches. Photo by Robert Pickles. |

Robert Pickles: Altogether we recorded 158 species of bird including 8 different raptors and 22 species of medium to large mammals. I really have to say something about the anacondas up there though. We encountered 6 during our expedition, four of which were estimated as being over 16 feet. To verify our size estimates we caught a large snake basking on the river bank and measured her length with a rope. She turned out to be 18 feet 2 inches in length with a maximum girth of 27 inches. It was quite incredible to see so many very large snakes. Why do they get so large here whereas in the Venezuelan Llanos they rarely record them over 16 feet?

Mongabay: Other than the giant river otters, what other endangered species are in the region?

Robert Pickles: Altogether we recorded the presence of 50 percent of Guyana’s threatened species including all the felids with several captures of puma in the camera traps, the presence of the mighty Harpy and crested eagles, the extremely elusive bush dog, abundant tapir and then just below the Falls is an important breeding ground for the giant South American river turtle.

Mongabay: What methods were used to find these animals?

Robert Pickles: We used a combination of camera traps, mist nets and drift spot counts to get an idea of the biodiversity of the region. We set up pairs of camera traps every 5 miles going upstream from Corona Falls which we left for up to 22 days, we then conducted dawn to dusk mist netting in different habitat types in the forest around camp as well as surveying the length of the river in a series of drift spot counts.

We used fairly basic techniques, but the beauty of our little study was in its ad hoc nature. Although our biodiversity surveying came as an offshoot of going up there to collect genetic samples from the giant otters, the fact is that we could come back with a glimpse, however imperfect that may be, of a rich biological diversity and the enormous potential of the area for future scientific studies working with endangered and normally elusive study species.

Mongabay: Did animals show fear of humans?

Camera trap photos from the expedition caught a puma Puma concolor (above) and a jaguarundi Puma yagouaroundi (below) on film. The puma photo captured a male following a female (tail just visible on far right). Photos by: Rob Pickles, Niall McCann, Ashley Holland. |

Robert Pickles: It was quite remarkable the number of game species such as paca and currassow that could be seen and approached with ease. We also encountered four tapir during the expedition. Unlike below the falls where they are very sensitive to human presence and will disappear long before you catch sight of them, because they had never been hunted up in the Rewa Head, they were entirely nonchalant about our presence and would quite placidly paddle just next to the boat as we drifted downstream.

Mongabay: What was the most surprising find on the expedition?

Robert Pickles: The thing which struck us most was the amount of wildlife we recorded in a short period of time and the ease with which that occurred despite the sub-optimal surveying conditions. Visiting the Rewa Head felt like we were walking in the footsteps of Wallace and Bates, seeing South America with its natural density of wild animals as it would have appeared 150 years ago. With the phenomenon of shifting baselines we forget what ‘natural’ and ‘pristine’ really mean and now think of places like the Rewa Head as being exceptional, whereas in reality this would have been the state of much of tropical South America, but the degradation has been going on for so long now that we are in danger of forgetting what it is supposed to be like.

THREATS TO THE REGION

Mongabay: What are the current threats to Rewa Head?

Traveling in Rewa Head: portaging the boats over a cataract upstream of Bamboo Falls. Photo by Ashley Holland. |

Robert Pickles: The starkest reminder that the area has no legal protection which we saw when traveling up to the Rewa Head was the presence of gold claim boards, dotted along the banks of the Lower Rewa, one even fixed up above a giant otter holt. These small-scale mining operations are extremely damaging in terms of erosion of the river bottom and banks, mercury pollution and the associated hunting which comes with it. To the Guyanese government’s great credit however, after becoming aware of the claims in the area and through local intervention, the claims were revoked.

Currently there is an oil drilling concession leased by Canadian firm Groundstar Resources Ltd which is spread across 780,000km2 of the Rupununi Basin including the Lower Rewa. Drilling has yet to begin though the company has been prospecting around the village of Rewa. The concern with this is that environmental safeguards are put in place and stringently adhered to. Oil extraction can be achieved with minimal environmental impact provided the company is diligent, but there is also concern as to whether the development of roads will lead to hunting encroachment above Corona Falls.

Then there is the question mark over logging. The entirety of the Rewa Head lies within a logging concession which will be worked in the following years.

Mongabay: Can you tell us about the company SSI and what role it’s playing in the future of Rewa Head?

Robert Pickles: Simon and Shock International is a US based logging firm which has recently signed a deal with the Guyanese government to allow it to extract timber from 400,000 hectares of forest. They are a selective logging firm and are only going after a few key species in that concession, namely greenheart and purpleheart. The company has stated its environmental principles and has listed a range of measures to mitigate degradation of the concession. But the unfortunate fact is that no matter how green your intentions are, it can be very difficult to prevent the creep of hunting into a forest once you’ve put a road in there.

Mongabay: How could REDD prevent incursions from logging and oil companies?

Crimson Topaz hummingbird Topaza pella in Rewa Head. In total nine species of hummingbird were recorded in the area. Photo by Ashley Holland. |

Robert Pickles: The idea is to alter the value of each commodity to make it financially worthwhile to keep the forests intact. Whereas currently the value for a carbon credit is low compared with oil or timber, though effective implementation of the REDD scheme, Guyana would hopefully see more direct financial gain from keeping the forests standing and unaltered than it would from extractive industries.

Mongabay: How do the Amerindians in Rewa Head view these threats?

Robert Pickles: Well, I think they see the logging and drilling as a mixed blessing. On the one hand jobs will undoubtedly be provided, bringing wealth to the local communities which cannot be denied. Access roads will also make it easier for them to get to Lethem and neighboring communities. On the other hand, villagers are unhappy about the borders of the logging concessions what they see as encroachment on their lands and are now challenging the lease.

There is an awareness of the importance of protecting the non-commercial livelihoods and the resources which the forests and river provide, but it’s coupled with a need to make money. The ecotourism industry in Guyana is still small potatoes and although it slowly seems to be increasing, with tourist lodges in Rewa, Surama and Yupukari, it is not yet at a stage where it can support many people full time.

Mongabay: Why is Guyana-with largely intact rainforests-important to climate change negotiations?

Robert Pickles: While it is obviously extremely important to tackle deforestation in the frontline countries where this threat is occurring, which is what REDD initially set out to do, it is equally as important that nations with large tracts of pristine forest and a less severe deforestation threat do not get marginalized, but receive due recompense for not taking the ‘economically rational’ path and fully exploiting those natural resources. Guyana is in an incredibly fortunate position in that it still retains 76 percent of its forest cover which constitutes some of the most carbon-rich forests of South America. As such, and with a president keen to offer his nation’s forests as part of the world’s carbon sink, Guyana should be embraced by the international community.

Mongabay: What are some current proposals for protecting Rewa Head?

Robert Pickles: The first step towards protecting that area is to get it on peoples’ radars. Interest from the scientific community has begun to be shown in the area from Panthera and Operation Wallacea which is sounding promising. The Amerindian villages are ideally situated for permanent scientific research stations to be built and many already have the infrastructure in place to support this. The Amerindians themselves are invaluable guides and making use of these skills in exploring the ecology of the Guianan Shield could be ideal.

If the Conservation International model of leasing logging concessions and holding them in preservation can be extended, then the Rewa Head might make an excellent candidate due to its naturally protected situation, biological richness and potential for scientific exploration.

Anaconda found in Rewa Head. Photo by Ashley Holland.

The jaguar Panthera onca is classified as Near Threatened: a previous six-week expedition to Rewa Head observed ten jaguars. Photo by: Ashley Holland and Gordon Duncan.

World’s largest spider, the goliath bird-eating spider Theraphosa blondii, from Guyana’s interior. Photo by: Gordon Duncan.

According to biodiversity report: “In the dry season huge sandy beaches are exposed in the Lower Rewa, providing a nesting ground for giant South American river turtles (Podocnemis expansa). The superabundance of eggs laid in these sand banks is a boon which many forest species time their breeding cycle to coincide with.” Photo by Ashley Holland.

Brazilian tapir Tapirus terrestrisi photographed 10ft from the expedition boat. The Brazilian tapir is classified as Vulnerable. Photo by: Robert Pickles.

Schneider’s dwarf caiman Paleosuchus trigonatus. Photo by: Niall McCann.

“Hand-axe sharpening grooves and geometric designs below Corona Falls on the River Rewa testify to the fact that there were once indigenous people inhabiting this area,” according to Biodiversity report. Photo by: Rob Pickles.

Logging and oil concession in Rewa Head. Map courtesy of Mike Robert Pickles.

Related articles

Norway to give Guyana up to $250M for rainforest conservation

(11/09/2009) Norway will provide up to $250 million to Guyana as part of the South American country’s effort to avoid emissions from deforestation.

Roads are enablers of rainforest destruction

(09/24/2009) Chainsaws, bulldozers, and fires are tools of rainforest destruction, but roads are enablers. Roads link resources to markets, enabling loggers, farmers, ranchers, miners, and land speculators to convert remote forests into economic opportunities. But the ecological cost is high: 95 percent of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon occurs within 50-kilometers of a road; in Africa, where logging roads are rapidly expanding across the Congo basin, the bulk of bushmeat hunting occurs near roads. In Laos and Sumatra, roads are opening last remnants of intact forests to logging, poaching, and plantation development. But roads also cause subtler impacts, fragmenting habitats, altering microclimates, creating highways for invasive species, blocking movement of wildlife, and claiming animals as roadkill. A new paper, published in Trends in Evolution and Ecology, reviews these and other impacts of roads on rainforests. Its conclusions don’t bode well for the future of forests.

REDD readiness plans for Panama, Guyana approved but rejected for Indonesia

(07/02/2009) The World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) has approved REDD readiness plans (R-Plans) for Panama and Guyana, and rejected a plan for Indonesia, reports the U.N. and the Bank Information Center, an advocacy group.

Norway to pay Guyana to save its rainforests

(02/05/2009) Norway will provide financial support for Guyana’s ambitious plan to conserve its rainforests, reports the Guyana Chronicle. Meeting in Oslo, Norway on Tuesday, Guyana President Bharrat Jagdeo and Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg signed a Memorandum of Understanding agreeing to establish a partnership to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD). The leaders will push for the incorporation of a REDD mechanism that includes low deforestation countries like Guyana in a post-2012 climate change agreement.

14 countries win REDD funding to protect tropical forests

(07/24/2008) Fourteen countries have been selected by the World Bank to receive funds for conserving their tropical forests under an innovative carbon finance scheme.

600 species of mushrooms discovered in Guyana

(07/21/2008) In six plots of Guyanese rainforest, measuring only a hundred square meters each, scientists have discovered an astounding 1200 species of macrofungi, commonly known as mushrooms. Even more surprising: they believe over 600 of these are new to science — that’s equivalent to a new species every square meter.

Implementing a butterfly farm: Iwokrama reserve’s latest sustainable initiative

(07/20/2008) Iwokrama, which lies in the heart of Guyana’s rainforest, is known worldwide for its innovative approach to preserving tropical rainforests and creating livelihoods for local communities. Their focus has been to create programs that utilize the forest sustainably, allowing for a mutual benefit between the people and the forest itself. Currently, Iwokrama has a number of initiatives under its umbrella, including eco-tourism, sustainable forestry, on-going research projects, and training programs. Amid these bustling projects, a new one has emerged: butterfly farming.

Geology, climate links make Guiana Shield region particularly sensitive to change

(06/14/2008) Soil and climate patterns in the Guiana Shield make the region particularly sensitive to environmental change, said a scientist speaking at a biology conference in Paramaribo, Suriname.

Private equity firm buys rights to ecosystem services of Guyana rainforest

(03/27/2008) A private equity firm has purchased the rights to environmental services generated by 371,000 hectare rainforest reserve in Guyana. Terms of the deal were not disclosed, but the agreement is precedent-setting in that a financial firm is betting that the services generated by a living rainforest — including rainfall generation, climate regulation, biodiversity maintenance and water storage — will eventually see compensation in international markets.

Guyana grants 1 million acres of Amazon rainforest to U.S. logging firm

(01/09/2008) Guyana has awarded a 988,4000-acre logging concession to a U.S. forestry company, reports the Associated Press.

Guyana’s forests offered as massive carbon offset

(11/26/2007) Guyana has offered up the entirity of its remaining forest cover as a giant carbon offset, reports The Independent.

Low deforestation countries to see least benefit from carbon trading

(08/13/2007) Countries that have done the best job protecting their tropical forests stand to gain the least from proposed incentives to combat global warming through carbon offsets, warns a new study published in Tuesday in the journal Public Library of Science Biology (PLoS). The authors say that “high forest cover with low rates of deforestation” (HFLD) nations “could become the most vulnerable targets for deforestation if the Kyoto Protocol and upcoming negotiations on carbon trading fail to include intact standing forest.”

Gold mining in Guyana damages environment, threatens Amerindians

(03/06/2007) Informal gold mining is causing environmental harm and human rights abuses in Guyana says a new report from the International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) of Harvard Law School’s Human Rights Program. Wildcat gold mining has been a serious problem in the Guiana shield countries of Brazil, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. Rising gold prices in recent years have only worsened the problem, as illegal miners have flooded the region clearing forest, polluting rivers, and making threats against indigenous people.