A chainsaw chugs into life and tears into the trunk of a tree as tall as a two-story house. Petrol and man work together as the chain sets its teeth into the wood and edges its way through. The tree creaks, leans, and falls with a great crash to a backdrop of whoops and cheers.

The sight and sound of tree felling is common in Indonesia, the country with the highest rate of deforestation in the world. The destruction of forests in this archipelago, draped like an emerald necklace across the equator, can be measured in hectares per minute. Today, though, is a good day for the conservationists.

The felled tree is an oil palm, or elaeis guineensis, the native of West Africa that has colonized millions of hectares of Southeast Asia’s formerly pristine forests. Its fruit is crushed, processed and bleached to form a flavorless, colorless oil. The invisible ingredient in everything from your chocolate to your shampoo.

Here in Aceh, as elsewhere in Indonesia, oil palm is known as green gold, reaping vast profits for companies based across Asia and the West. Which makes cutting down palms at the height of their productive life very unusual indeed.

Building where plantation workers lived. Photo by Tomasz Johnson Building where plantation workers lived. Photo by Tomasz Johnson

|

This 800 hectare plantation was planted illegally on the Leuser Ecosystem, one of the world’s most diverse and important wildlife habitats, home to the Sumatran rhino, tiger, elephant, and orang utans. If these species fail to survive here, they probably will not anywhere. Illegal plantations are in themselves nothing unusual – this one in Tamiang district, in the semi-autonomous province of Aceh, stood untouched for more than a decade. But in the Leuser Ecosystem the conservationists are fighting back.

“I’ve seen people accept it and say ‘okay, people have moved in and planted trees, let’s redraw the boundaries,'” said Mike Griffiths, a native New Zealander who co-founded the Leuser International Foundation (LIF). “But you’ve got to fight it, to fight the tide of destruction.”

When Griffiths first trekked through into the depths of Aceh’s forests three decades ago, he was struck by its beauty. Tall, hardwood dipterocarp trees reached to the sky, casting their green canopy over a breadth of flora and fauna to rival any on the planet.

“The lowland forests were absolutely stunningly beautiful,” he said. “It reminded me of a Gothic cathedral; tall pillars supporting this great canopy.”

The vast majority of Aceh’s inhabitants lived within 10 kilometers of the coast and the forest straddling the boundary of North Sumatra, stretching across the island’s interior, had evolved in the absence of man.

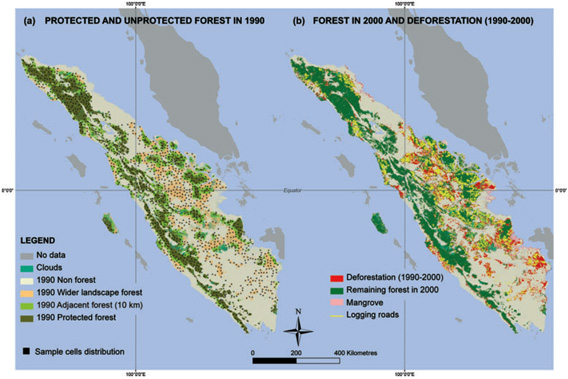

(a) Protected and unprotected forests in 1990 for the main island of Sumatra and the smaller island of Siberut, including adjacent unprotected land lying within 10 km of protected area (PA) boundaries and the wider unprotected landscape, and showing the spatial distribution of the 1264 sample cells (25 km2). (b) Remaining forests in 2000, deforestation and logging trails occurring during the period 1990–2000 (UTM projection, WGS84). Protected areas (PAs) protecting mangroves or created after 2000 are not shown. MAPS available at sumatranforest.org |

Then came the logging and the poaching, the settlements and the plantations. The virgin interior was stripped of most of its valuable timber, those grand dipterocarps. The government policy of transmigration moved poor communities from overpopulated islands to the sparsely inhabited, outlying regions like Aceh, bringing human interference to the ecosystem. And when demand for palm oil began to rise, the lowland forests offered the tempting combination of perfect growing conditions, cheap land and no population to make a fuss.

Griffiths, then an executive in the Acehnese oil industry, began documenting the wildlife of the forests in the early 1980s, setting up camera traps to capture a cast of mammals straight out of the Jungle Book. Over the next 20 years, consumed by a passion to preserve what he had found, he and a small but powerful coterie of like-minded Achenese politicians fought the forces of deforestation. Together, slowly and steadily, they built up a consensus of opinion within the Acehnese political establishment, community organizations and, vitally in the staunchly Muslim province, among religious leaders that the area that came to be known as the Leuser Ecosystem should be saved.

Saving the highlands surrounding mount Leuser came early on; they lacked the grand hardwoods or soil to exploit. But the lowlands surrounding it needed to be protected in law too. It is in the lowlands that the elephants, tigers and rhinos prowl. Maintaining the integrity of the whole of their wide-ranging migration patterns was vital.

“The deeper into the forest you get the less interesting it gets; if we weren’t going to rescue this lowland forest there wouldn’t be anything,” said Griffiths, who is now employed by the Leuser Ecosystem Management Authority of the government of Aceh. “Transmigration was the golden child of [former Indonesian president] Suharto and we got him to close the settlements down. People said you could never do that. Shutting down roads? Never been done before, but we did it. When people saw that, they started to think we could save it.”

The Leuser Ecosystem is now protected by two acts of parliament and defined as a National Strategic Area, providing a strong mandate to convict people who make the wrong decisions. The animal population has gradually recovered. While there are no exact estimates of the numbers, Griffiths believes there are around 300 tigers, 100 rhinos and 600 elephants. But the wrong decisions are still being made and the process of enforcing the law can be a lengthy and diplomatic process.

Lack of coordination and political power struggles between the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Ministry of Forestry mean that roads are still carving their way through the forest. Satellite images show a thin, but distinctive, white line beginning to scythe the green expanse into two parts. The road project could prevent mammals, which will not cross it, from completing their migrations. But roads make money; from contracts, the timber by-product and the land they open up. So too does palm oil.

Winning the diplomatic battle to secure the removal of the 800 hectare plantation took six months, the man who won it Rudi HP. Now a conservation manager for the Leuser Ecosystem Management Authority, the sharp and deceptively tough Rudi grew up on the outskirts of the forests and witnessed first hand devastating floods that have repeatedly hit the district. Only two years ago floods washed away more than 2,000 homes, displacing thousands of people and leaving more without clean water supplies. Climate change and deforestation have been identified as greatly exacerbating the problem; forests prevent soil running, causing landslides, and hold more water than farms or plantations.

As we watched his team cut down the palms I asked Rudi why, as the plantation was illegal, he could not just rip it down straight away. He shot me a patient look. “It’s easier like this.”

Rudi. Photo by Tomasz Johnson. |

The plantation was set up by a businessman from Medan, the capital of North Sumatra, five hours hard driving away. He is involved in plantations elsewhere in Indonesia as well as the transport industry and is almost certainly politically connected. The process of legal enforcement is rooted in diplomacy and it took a lot of meetings to get to this point, though Rudi admitted, perhaps with understatement, that the plantation owner was still quite angry with him.

Rudi’s work is far from over. There are an estimated 15,000 hectares of palm oil in Tamiang province alone that need to be removed to reestablish a north to south corridor for the elephants.

“The first thing is to make people understand the important of conservation, to get that message across,” Rudi said. “There are people in this area that are keen on conservation, who do care about the forests here. My role is to mobilize their passion and their desire to help.

“In the next five years I’d like to see a total stop to all illegal logging of forests, conversion of forests, illegal settlements and all roads should be stopped and restored. The Leuser Ecosystem should be restored to its former beauty and integrity.

“I have the power to do it. But I also have a broad coalition of support, from communities, from civil society organizations and the police. It can be done.”

Rudi’s team worked their way through the mud and muggy heat on a hillside, felling oil palm after oil palm. At the bottom of the small valley stood two slightly dilapidated timber buildings, home to the 14 workers and a supervisor who tended to the palms.

Tanjung, a shy 42-year-old dressed in a pair of tatty shorts and a t-shirt, said he had come from his home near Medan to work on the plantation around ten months ago. His story was not uncommon. In the employ of the businessman who owned the plantation he had traveled around the palm oil heartlands of Indonesia, Kalimantan and Sumatra, working where he was needed. Along with the other workers living in the plantation he earned around £2 a day. Most of that was sent home to his family back in North Sumatra. Around half of all Indonesians survive on less than £1.20 a day and in Tanjung’s home village there was no work for him. He admitted that this was not a good job, but the only one he could get.

He shuffled nervously when asked what he thought about the destruction of the plantation.

“It’s not up to me whether I like it or not,” he said. “If that’s the law then it has to be done.”

Oil palm plantation and forest in North Sumatra |

Most of the workers and the supervisor had already left by the time we arrived. After the painstaking process of negotiating the removal of the palms it had come as no surprise. Tanjung expressed hope that he would be looked after by his employer, probably moved to a plantation elsewhere, and he said he would wait until he was told what to do.

Migration from overpopulated parts of Indonesia to the less populated, outer-lying islands is ingrained in the demography of modern Indonesia. Suharto’s transmigration policy led to millions of poor, landless people from Java, the Madurese islands and Bali moved as far and wide as Kalimantan, in the Indonesian portion of Borneo, and the tribal heartlands of Papua. The palm oil industry tapped into the same paradigm. Migrants without access to land and used to working for wages in rice fields or plantations provide the ideal itinerant labor force for palm oil companies.

Transmigration fanned the flames of ethnic tension, with migrants and indigenous communities competing for the same scarce resources in some areas, tensions that flared up into horrific outbreaks of violence in Kalimantan. In Tamiang the majority of the palm oil owners and employees are people from other areas, though Rudi said the district has been thankfully without problems.

“The people of Tamiang don’t want to work in other people’s plantations,” he said. “They’d prefer to open up their own small plantations and work for themselves rather than someone else. So of course a lot of labor comes from outside.

”The Tamiang don’t have a problem with people coming in. There are no social rifts or problems. But what they see is all the good, productive land has been taken over by outsiders which means there is less and less land for Tamiang people. Some day the people of Tamiang will say what about us? What about our futures?”

Nonetheless the cheap and ready supply of labor is good for business. Along with easy access to land and the unrivaled productivity of the oil palm, it contributes to the profitability of industry. Oil palm plantations boasts higher yields per hectare than any other oil producing crop, providing a competitive edge over soy or rape seed oils. The ubiquity of processed fats in the modern food industry, and the rise of fat consumption in the burgeoning middle classes of China and South Asia, have sent demand soaring.

Sumatran orangutan in North Sumatra |

That demand has helped drive deforestation in Indonesia to such high levels. Aceh alone loses around 20,000 hectares of forest each year. In Indonesia the figure jumps to 1.87 million hectares a year, largely in Sumatra and Kalimantan. The release of the carbon stored in those forests has driven palm oil to the forefront of the climate change agenda. Deforestation contributes almost a fifth of annual carbon emissions, more than the fossil fuel burned in all of the planes, trains and automobiles in the world. Put simply, climate change will not be solved without halting the destruction of forests.

As we had driven along the dirt track into the illegal plantation, jostled as the four-wheel drive van was thrown around, the scale of palm oil expansion in Aceh was striking. For mile upon mile we passed, either side of the road, row upon row of oil palms. Planted in regimented lines, the fronds struck out like spiders legs and the bunches of red fruit nestled at their base. Beneath the tall trunks lay little but a low carpet of scrub and ferns, a translucent veil of green set over the desolation.

A study by the Zoological Society of London found that very few mammal species will enter plantations, particularly endangered species like the Sumatran tiger. The study recognized that converting land to palm oil plantations has major detrimental effects on most land mammals, making it all the more important that forest enclaves like the Leuser Ecosystem remain intact if the species, their numbers dwindling, are to survive.

But palm oil is now vital to the economies of Aceh and Indonesia. More palm oil is produced in the archipelago than in any other country in the world, though it is pipped in the export stakes by neighboring Malaysia. The advent of biofuel produced from palm oil has also increased demand. And while environmental concerns have tempered attitudes to it in Europe, when prices of crude palm oil are low enough to make it an economic alternative to fossil fuels it is bound to find a market elsewhere. The green gold continues to generate huge revenues for business and government and, where it has been managed conscientiously, has brought much needed infrastructure to poor communities. The balance between economics and conservation, however, has not yet been struck.

In Leuser the struggle continues and Griffiths is confident that after all the battles he has fought these forests can bid farewell to the green gold. The fallen palms will lie where they are until they decompose, their nutrients nourishing the recovering forest with a poetic sense of justice. Griffiths says that to get the “grand forest” he first encountered back will take at least 250 years, as the progeny of those ancient hardwood trees grow tall.

“You don’t do these things overnight,” he said. “We’ve been fighting for 20 years. We knew exactly where we were going and we’re still not there yet.

“It will take time, but in five to ten years we’ll have the greatest conservation area in Southeast Asia.”

tomaszjohnson -at- hotmail.com