Understanding the web of social groups involved in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is key to containing forest loss, argues a leading Amazon researcher writing in the journal Ecology and Society.

Philip Fearnside of the National Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA) reviews nine actors that have had significant roles in deforestation and reports differences in why they deforest, where they are active, and how they interact with each other. The actors range from the poor (landless migrants and state-sponsored colonists drawn by dreams of a better life) to the rich (well-capitalized farmers and large-scale ranchers); from the opportunistic (goldmining garimpeiros) to the desperate (landgrabbing grileiros); and from free-market capitalists (drug traffickers and sawmill operators/loggers) to those who have few alternatives (debt-bondage slaves). The groups are the product of migration, which, in the words of Fearnside, “involves not only the movement of people, but also the movement of investment.”

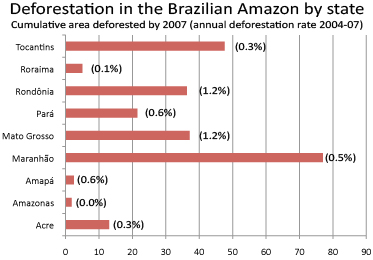

Deforestation by state in the Brazilian Amazon |

“The type of actor that is moving into an area of forest is of primary importance in determining the rate of spread of deforestation. Types of actors cover a full range in terms of wealth, legality, and the intensive or extensive nature of their activities.”

Poor migrants usually form the base of the chain, supplying the brawn to clear forest. Wealthier groups supply the capital.

“Landless migrants have significant roles in clearing the land they occupy and in motivating landholders to clear as a defense against invasion or expropriation,” writes Fearnside, alluding to the need of landowners to tear down forest as a means to establish land claims in a region where law enforcement and governance are in short supply.

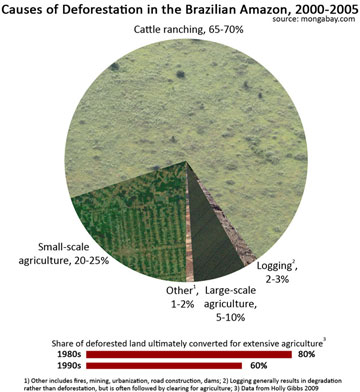

“Colonists in official settlements and other small farmers also are responsible for substantial amounts of clearing, but ranchers constitute the largest component of the region’s clearing,” Fearnside writes, adding that ranchers and agribusiness are “most responsive” to changes in commodity prices but receive “substantial subsidies.”

Poor migrants from the north

People from the northeast Brazil, a poor but populous and politically resourceful region, figure prominently in deforestation. Typically arriving in the Amazon as as colonists or debt slaves (usually unaccompanied males but sometimes entire families), these Brazilians become small-scale farmers, laborers on ranches, goldminers, and land invaders, and have substantial effects on the landscape.

“Migration from Maranhão has completely transformed the central portion of the state of Pará, centered on Marabá. This entire area is now degraded, including virtually every fragment of forest left in the deforested landscape,” writes Fearnside. “The steady arrival of up to 100 families a week in Marabá has supplied a virtually inexhaustible source of settlers and landless migrants to central Pará.”

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has typically occurred along roads, although illegal activities can result in unusual patterns of clearing. Fearnside writes: “Significant areas of deforestation can result from use of money from illegal activities elsewhere, for example in areas held by drug traffickers and money launderers in the Terra do Meio between the Xingu River and the BR-163 Highway in Pará. The Terra do Meio is an area the size of Switzerland that is largely outside of the control of the Brazilian government.” “The power of the underground economy to affect deforestation in the Terra do Meio was demonstrated most clearly in 2003 when a 6200-ha clearing appeared in the area in only 3 weeks’ time. The site, known as ‘the revolver’ because of the shape of the clearing, is far from any roads and is in an area that, because of its remoteness, has been calculated to have the lowest farm-gate values of beef cattle in Amazonia. The legitimate economy, therefore, cannot explain clearings of this kind.” Image courtesy of Google Earth |

Hardship leads some migrants to fill the ranks of organized groups such as the Movement of Landless Rural Workers (MST), who occupy land, sometimes illegally, or become outright criminals, invading legal forest reserves and Indian reservations at the behest of developers seeking to convert these lands to pasture or farmland. Land invaders are usually compensated for their services.

“Landgrabbers, or grileiros, are important in entering public land and beginning the process of deforestation and transfer of land to subsequent groups of actors,” writes Fearnside. “These include sawmill owners and loggers, who play an important role in generating funds for clearing by other groups, ranging from landless migrants to large ranchers. They also build endogenous roads, facilitating the entry of other actors.”

Affluent migrants from the south

Meanwhile capitalized farmers, notably large-scale agribusiness for soy production, are a powerful agent in land use change in southern Brazil, particularly Mato Grosso, Santarém, and eastern Rondônia. These farmers, who often originate in Brazil’s agricultural heartland in Southern Mato Grosso and Rio Grande do Sul, respond to commodity markets and serve as a political impetus for new infrastructure development that facilitates further agricultural expansion and deforestation. These investments (a sizable proportion of Brazil’s $320-billion plan to expand and improve roads, dams, and ports across the country will be spent in the Amazon) will spur further influx of migrants to the region, contributing to the cycle of deforestation.

“Future movements of actors will be influenced by major infrastructure plans,” writes Fearnside.

Containing deforestation

|

While continued deforestation may seem inevitable, Fearnside says that sound policies could avoid the worst outcomes. Implementing its land titling system and “stopping the practice of regularizing land claims” would help Brazil establish rule of law in the Amazon, enabling authorities to enforce environmental rules that protect forests as well as reducing the need for legitimate holders to clear their land to establish a claim on it. At the same time, discouraging migration by generating employment in “source” areas, “exercising restraint” in approving new roads, and reducing subsides — including low interest loans to deforesters — would alleviate pressure to deforest in the Amazon. Creating new protected areas and promoting economic alternatives to deforestation, including payments for environmental services and sustainable harvesting of forest products, could increase standards of living in the region without the need to clear additional forest.

“Most fundamental is continued progress in creating mechanisms to reward the environmental services of standing forest as an alternative foundation for the economy in rural Amazonia,” concludes Fearnside.

Fearnside, P. M. 2008. The roles and movements of actors in the deforestation of Brazilian Amazonia. Ecology and Society 13(1): 23. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss1/art23/