|

|

The UN Summit on Climate Change isn’t for three months, yet the political temperature has been rising steadily over the summer. This heat is focused on the three big players at the summit: China, India, and the United States with a special temperature reserved for the last.

These three juggernauts are vital to the summit, because it is expected that any of these countries could single-handily ruin negotiations and derail the summit. If the summit ends in indecision or with a watered-down agreement, expect that it will because of one or more of these three countries. Historically, these are the three major holdouts when it comes to tackling climate change, and whether one likes it or not they hold the key to the world’s future.

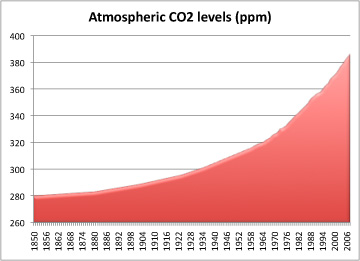

Atmospheric levels of CO2 in parts per million (ppm) from 1850-2006. |

Of course, the biggest of the three is also the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the world: the United States. It has received its share of heat recently from the rest of the world. Yesterday, the EU called on the United States to “deliver” on its promise to cut greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. The statement was made by Sweden’s Environment Minister Andreas Carlgren, who added that “it’s the real substance of credibility that will be judged.” Sweden currently holds the revolving presidency of the EU.

The remarks were largely addressed at senators in U.S. who will soon be looking at the climate bill that passed the House. If the current debate over health care is any indication, the fight in the Senate could turn ugly quick and it is not improbable that the bill could find itself floundering. If this were to happen, however, it could be disastrous for the summit in December: it would mean the Obama Administration would have to walk into meetings with its tail between its legs, since the administration would have nothing whatsoever to prove its sincerety.

To do what little it can to prevent this from happening, the EU is sending a delegation to lawmakers in Washington this month to explain their stance on climate change—and probably poke and prod the lethargic senators of the U.S. The difficulty is that senators don’t have to worry about international relations, while the Obama Administration does.

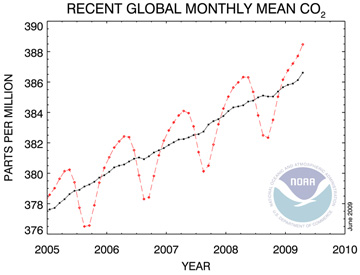

Monthly atmospheric CO2 records from sites in the SIO air sampling network 2005-June 2009 . |

On Sunday the EU announced that it had succeeded in bringing down its collective emissions for a fourth year in a row (although 2008’s drop in emissions was largely due to the global recession). The EU’s emissions are now 6.2 percent below 1990 levels, whereas the United States’ emissions have actually risen 15.9 percent above its 1990 levels. One would think this would give some leverage to the EU’s delegation (and perhaps some advice on how to lower emissions), but one also wonders if the United States is really ready to listen.

But pressure is building from more than just the EU. India has recently made some cryptic, but perhaps telling statements, about its stance—or rather the flexibility of its stance—on climate change. Jairam Ramesh, the Environment Minister in India, recently met with China’s top climate change negotiator in Beijing. At the meeting Ramesh told reporters that the developed world should call his nation’s “bluff” on climate change. He said that if wealthy nations, such as the United States, called for a 40 percent reduction in emissions by 2020 from 1990 levels it would force India’s hand.

“That’s a game changer,” Ramesh told reporters. “It would be very difficult for me, as an Indian minister, not to respond if developed countries accept this proposal. The fat would be in the fire, our bluff would be called.”

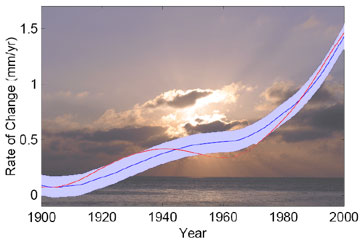

Changes in sea levels 1900-2000. |

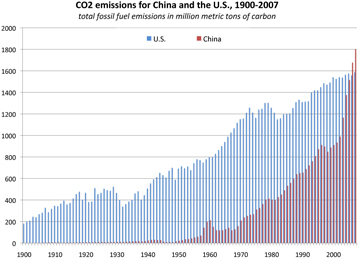

So far, the bill passed in the United States’ House has set a target of cutting emissions by 17 percent by 2020—leaving India room to wiggle with its own targets and not by any means putting the ‘fat in the fire’. Both India and China have stated for years, if not decades, that they believe the developed world, especially the United States, should make deeper cuts than developing nations, i.e. themselves. They also argue, rightly, that their emissions are still far below the United States’ per capita.

Next comes the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases since 2006, China, with some intriguing—one might say hopeful—recent developments. Despite being seen as throwing a wrench into previous climate change negotiations, China appears recently to have had at least a slight (and maybe a big) change of heart.

Last week Chinese legislatures announced that their country will “strive to control greenhouse gas emissions” and consider new laws to combat climate change. Such rhetoric is unprecedented. The legislators made it clear however that any new agreement not put up trade barriers, but this is an issue that can be worked around if the will is there.

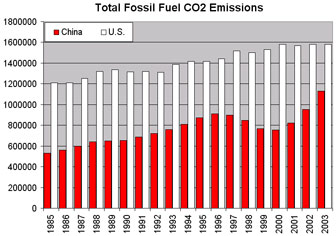

CO2 emission China and the United States from 1900-2007. |

Only a week before this, a report by Chinese scientists recommended that the nation begin drawing down emissions after 2030. Although not binding, the announcement was noteworthy as it was the first mention from China of a target year for capping its runaway emissions.

In the past China has largely sat on its haunches when it came to climate change, but the news coming out of China recently appears to signal that they are willing to really negotiate.

As always it appears the focus returns to the United States, who has continually argued that it’s not fair for the U.S. to have to lower emissions if China, India, and other developing nations don’t have to do the same. While there is a point to this argument, it would be appear more sincere if the United States had actually been attempting to lower emissions over the past decade. As it is, the country’s continuous fallback on ‘developing nations aren’t doing enough’ looks like a stalling technique of the worst kind. The United States is the largest—by far—contributor of greenhouse gases: in the past 150 years the nation has produced a staggering 29 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Still the military and economic powerhouse has yet to recognize its moral duty to make some significant changes quick.

Total fossil fuels CO2 emissions between China and the U.S. from 1985-2003. |

Many eyes are on the Obama Administration. It has promised such changes both to people at home and to nations abroad. Thus far, however, Obama has yet to take-up the leadership role many hoped he would on the issue. He has yet to make a major speech on the issue, and when he does talk about climate change it’s with little vigor, especially when he’s in the states. The administration also relinquished any control over the bill that wait in the Senate. Without direction, the bill has become the product of endless haggling, lobbying, and petty selfishness, and it is doubtful that the Senate will improve matters. Many environmentalists believe the bill is pathetic, yet still want to see it passed because it would in the very least send a message to the world that for the first time the United States government is taking climate change seriously.

There is in fact little question that the rest of the world is taking it seriously. Pope Benedict XVI, who has been talking about climate change for years, just installed solar panels on his house in Germany-after doing so at his larger house in Rome, the Vatican. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, who has called climate change ‘the greatest collective challenge we face’, just returned from a trip to the Arctic to drum up support for the upcoming summit. Last month, ten African nations met to unify their stance on climate change and demand aid from wealthy nations, arguing that African nations are suffering greatly from climate change thought they contributed little to the problem. And this weekend, the president of the Maldives—the world’s most endangered country from climate change since one meter rise in sea levels could swamp the entire country—in an emotional speech told the world not to accept a “suicide pact” when it comes to climate change.

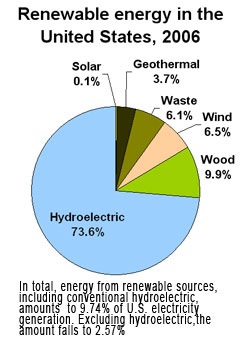

In 2006 renewable energy sources amounted to 9.74 percent of the U.S.’s electricty. |

“The world has an opportunity to come together and prevent the looming environmental catastrophe,” President Mohamed Nasheed said. “This opportunity as we all know is called Copenhagen, and let’s be very frank about this: Copenhagen can be one of two things. It can be an historic event where the world unites against carbon pollution in a collective spirit of cooperation and collaboration, or Copenhagen can be a suicide pact. The choice is that stark.”

Nasheed for one put his money where his mouth is. In his speech he announced that his country would become carbon neutral in a decade. That’s one target no one else has the guts to mention. Of course, when the water is rising, it’s a lot easier to see the need to start collecting buckets.

Like the water surrounding the Maldives, the political heat is rising. Developing nations across the world—facing droughts, water shortages, food crisis—have been pleading for a tough-as-nails agreement. Europe has extended its hand—once again—as an arbiter in the discussions. India has, in fact, shown its hand by asking others to call its “bluff” and push for a strong goal. China, dropping hints of a target, has made statements that make it appear the naiton is finally ready to negotiate—seriously.

But the question remains: does the United States in fact feel this heat? And even if it does, one still wonders: does it care?

Related articles

Maldives president tells world: ‘please, don’t be stupid’ on climate change

(09/01/2009) “Please, don’t be stupid,” Mohamed Nasheed told the world regarding the need to act decisively against climate change. To underlie his message, Nasheed announced that his country will become carbon neutral in ten years.

Greenhouse gas emissions drop in the EU for the fourth year in a row

(08/31/2009) In 2008 greenhouse gas emissions in the EU fell 1.3 percent, the European Environment Agency (EEA) said today. This figure measures only the emissions in the 15 EU countries that have commitments to reduce emissions, however when all 27 members of the EU are included, greenhouse gas emissions actually fell further: 1.5 percent.

China moves forward on global warming: top scientists recommend emissions peak in 2030

(08/17/2009) In a move that many have seen as a step forward for China in terms of its willingness to combat climate change, the nation’s top climatologists have released a report recommending that China begin drawing down greenhouse gas emissions after 2030. The report comes just four months before a widely anticipated global meeting to set up a new international framework to combat climate change in Copenhagen, Denmark.