- Camels are among the most recognizable animals on the planet, yet few realize that wild populations are at a high risk of extinction.

- Of the world’s two camel species, the Dromedary camel, characterized by a single hump, has already gone extinct in the wild. The second species, the two-humped Bactrian camel, was on a similar trajectory until very recently, but still less than 1,000 of the world’s 1.4 million Bactrians are wild.

- John Hare, founder and director of the Wild Camel Protection Foundation, argues that it does. Hare says the world will be a poorer place if wild Bactrian camels are allowed to follow their cousins into the sunset.

Update: John Hare died January 28, 2022 at the age of 87.

An interview with John Hare of the Wild Camel Protection Foundation

Camels are among the most recognizable animals on the planet, yet few realize that wild populations are at a high risk of extinction.

Of the world’s two camel species, the Dromedary camel, characterized by a single hump, became extinct in the wild 2,000 years ago. The second species, the two-humped Bactrian camel, was on a similar trajectory until very recently, but still less than 1,000 of the world’s 1.4 million Bactrians are wild.

The abundance of domesticated Bactrian camels relative to wild camels doesn’t address the question of whether it matters if another species of camels goes extinct. John Hare, founder and director of the Wild Camel Protection Foundation, argues that it does. Hare says the world will be a poorer place if wild Bactrian camels are allowed to follow their cousins into the sunset. He notes that wild and domesticated Bactrian camels are thought to have diverged some 700,000 years ago and have a 3.5 base genetic difference, more than twice the separation between humans and chimpanzees, suggesting that they may even be independent species.

Wild Bactrian camel. Photo by John Hare. |

Wild camels are exceedingly rare today for a variety of reasons, most significantly because of man’s ambition to convert them into beasts of burden. A few populations managed to avoid the fate of their brethren by living in one of the world’s harshest environments: the Gobi desert of China and Mongolia, an area lacking in fresh water and buffeted by fierce sandstorms and a temperature range of -40 to 56°C (-40 to 133°F). But while wild camels have thrived under these conditions, along with surviving with more than 40 open-air nuclear tests conducted at Lop Nur in the Gobi by the Chinese military, over half of which were more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, the greatest threat to them today comes from hunters hungering for their meat.

Hare, working with local partners and the Chinese government, is fighting to ensure these camels will outlast this final threat by establishing one of the world’s largest nature reserves and encouraging local populations to embrace wild camels as a source of pride, rather than a source of protein.

Hare says these efforts could yield benefits beyond saving the rarest camel.

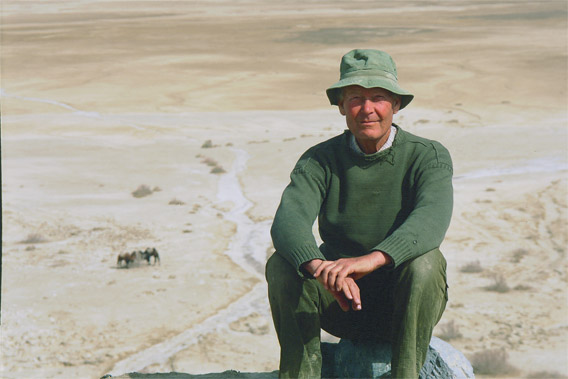

John Hare. |

He commented: “The greatest contribution as a result of conserving the wild Bactrian camel comes in the form of answers to the following: How did they survive 43 atmospheric nuclear tests? Is there any linkage between salt water and an ability to withstand radiation? The answers to these two questions could be highly beneficial to mankind.”

Hare notes that differences between wild and domesticated Bactrian camels are unsurprising given they are thought to have diverged some 700,000 years ago.

In an August 2009 interview with mongabay.com, Hare discussed his efforts to protect the planet’s last remaining wild camels.

Note: If you are interested in meeting the Wild Camel Protection Foundation, John Hare will be presenting at the Wildlife Conservation Network’s Expo in San Francisco on Saturday, October 3rd, 2009.

An interview with John Hare

Mongabay: What is your background and how did you get interested in working with the Bactrian camels?

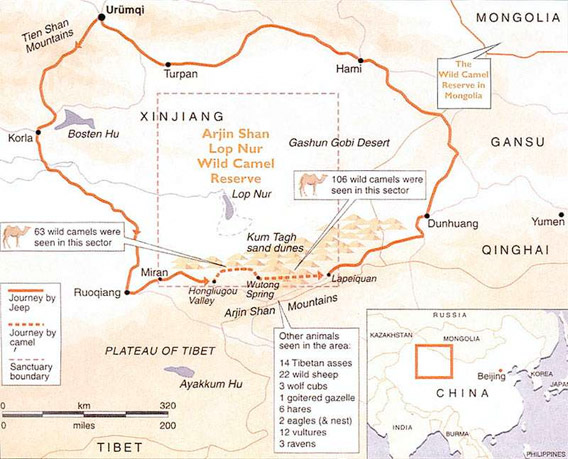

John Hare: I worked for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in Nairobi on conservation issues and prior to that had worked in Africa. The work in Africa included working with Dromedrary camels. While at UNEP I had a chance meeting with a Russian professor which led to my inclusion on the joint Russian-Mongolian Expedition to the Gobi Desert. I was the wild camel man on that expedition. I was so interested in the Gobi and the wild camel that I left UNEP and set up the Wild Camel Protection Foundation, a UK registered charity. We helped the Chinese establish one of the biggest nature reserves in the world in China’s former nuclear test area (155,000 square kilometers) where the wild Bactrian camel survives. It is the eighth most endangered large mammal on the planet and is critically endangered. In China it survives on salt water with a higher salt content than sea water. It also survived over 43 atmospheric nuclear tests, over half of which were more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. DNA tests confirm that the wild Bactrian separated from the domestic Bactrian camel 200,000 years ago. It has a genetic base difference with the domestic Bactrian of 3 percent. We have a 5 percent difference with a chimpanzee.

|

Mongabay: What is the biggest threat to camels?

John Hare: Man in the form of illegal miners looking for gold and iron ore who enter the reserve illegally and shoot the wild Bactrian camel for food or lay land mines to blow it up to eat. The reserve staff are constantly occupied in trying to stop these activities. Wolves are also a threat but they cannot enter the desert’s interior because of the lack of fresh water.

Mongabay: Why is wolf predation a threat to the species? Have wolf populations changed or is the population so low that natural predators now put it at risk?

John Hare: The reason for the increase in the wolf population is because the Chinese government has banned herdsmen from carrying guns to protect their flocks. There has been a notable increase and while on an expedition with domestic camels in the area (I always travel with camels and not vehicles), our domestic camels in 2006 were attacked at night by three wolves.

Mongabay: Is there a threat of inter-breeding with domestic camels?

John Hare: In some areas to the south of the Reserve, but as domestic camels are rapidly decreasing, the threat gets less every year. Not that I like to see the drop in domestic Bactrian camel numbers in any way, but ‘progress’ is forcing them out.

Mongabay: Is the Chinese government supportive of your efforts?

John Hare: The Chinese government is very supportive of our efforts and the reserve has recently been upgraded to a National Reserve with the same status as the Panda Reserve.

Mongabay: Could conservation of wild Bactrian camels benefit domestic camels? Are there other benefits to Bactrian camel conservation?

John Hare: The greatest contribution as a result of conserving the wild Bactrian camel comes in the form of answers to the following: How did they survive 43 atmospheric nuclear tests? Is there any linkage between salt water and an ability to withstand radiation? The answers to these two questions could be highly beneficial to mankind.

Mongabay: Wild Bactrian camels can apparently drink salt water, while domestic Bactrian camels will not. Are scientists looking into this behavior/adaption?

Camel expedition members in the field. |

John Hare: I have tried repeatedly to get scientists to look into this remarkable factor of salt water assimilation. I know I can get the Chinese Government to allow a scientist to go in to investigate and indeed I am in touch with a scientist who is anxious to undertake such an investigation. Unfortunately, lack of funding has always been the overriding problem.

Mongabay: Do you conservation efforts involve working with local communities?

John Hare: We have initiated a massive awareness-raising program in schools and villages surrounding the reserve. A booklet about the wild camel which I wrote is used in Chinese schools and has been translated into Mongolian, Chinese and Kazakh. It is called ‘The King of the Gobi’ and we are in urgent need of funds to reprint the booklet.

Mongabay: What are the biggest challenges of working in the field?

John Hare: The huge distances – the reserve is nearly as big as Texas – and the extremely hostile climate which varies from -40 Celsius (-40°F) in winter to 56 Celsius (133°F) in summer.

Mongabay: Is there any potential for tourism to support Bactrian camel?

John Hare: Tourism potential is limited – to the east of the reserve is a military area – and the Chinese are wary of tourists in this area. No-one can enter the reserve without special permission.

Mongabay: How can people in places like the U.S. help your efforts?

John Hare: By joining the Wild camel Protection Foundation and thereby gaining information and updates on a regular basis. By donating much-needed funds to help with our research and awareness-raising.

Mongabay: Do you have any tips for aspiring field conservationists?

John Hare: Don’t take ‘no’ for an answer, but quietly battle on. Be patient when dealing with government officials. Be resolute when conditions are extremely hostile! Above all BE PATIENT.

Wild Camel Protection Foundation

If you are interested in meeting the Wild Camel Protection Foundation, John Hare will be presenting at the Wildlife Conservation Network’s Expo in San Francisco on Saturday, October 3rd, 2009