Just weeks after a bloody conflict between indigenous protesters and Peruvian police, Hunt Oil begins exploration in the Peruvian Amazon.

Barely six weeks after a dozen Amazon natives were gunned down by the Peruvian Army in the oil town of Bagua for protesting the cozy relationship between Big Oil and the government of President Alan Garcia, I find myself on the banks of the Mother of God River in Salvacion, Peru, wondering if all those folks died in vain.

Any day now, the bulldozers will be moving in as Texas-based Hunt Oil Company – with the full go-ahead of the Peruvian government — fires its first salvo in its assault against the million-acre pristine rainforest wilderness of the little-known and largely unexplored Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. By the time you read this, the choppers will probably already be here, womp-womping their way along the very edge of Manu National Park to supply the seismic survey crews whacking their way through the jungle and blowing off explosives to see what riches lie below the surface. The local natives that the “reserve” was created to protect, like so many before them, are getting ready to have their lives irrevocably altered, and are wondering how to react to this invasion.

In other words, it’s business as usual for the Planet Eaters in the Amazon jungle, as if Bagua never existed at all. I could write a book – indeed, I am writing a book – about the carnage going on down here in the heart of the Mother of God. Here is just a taste of what I’ve found so far in my first two months in Peru:

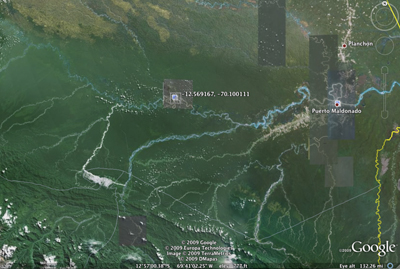

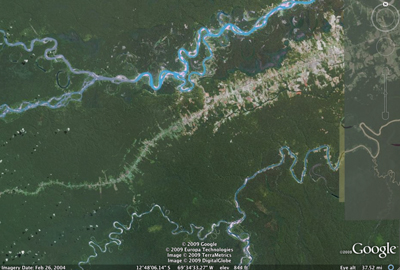

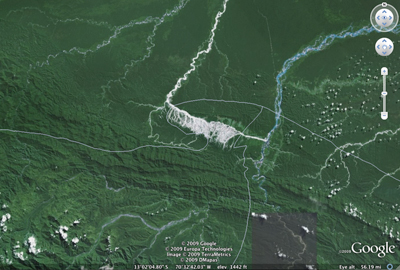

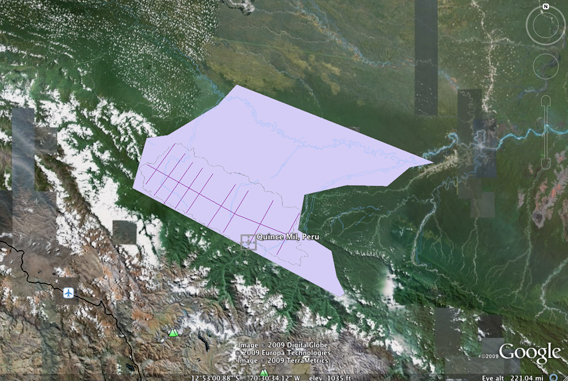

Madre de Dios, Peru. Deforestation from the Transcoeanic highway and gold mining activities on the Rio Huaypetue are clearly visible. Amarakaeri Communal Reserve is in this area. A shape file detailing the Block 76 should be available shortly |

If you carefully read all the reports from the massacre at Bagua, you will notice that those protesters (and other natives from all over the Peruvian Amazon, including those here in Amarakaeri) are saying that, by and large, modern-day Amazon natives are not categorically opposed to all oil and gas drilling (or logging, or mining, or ranching) on their ancestral lands – no matter how much the tree-hugging environmentalists in the U.S. with their “noble savage” fantasies don’t want to hear it.

As a rule, what modern-day Amazon natives are opposed to – and rightfully so – is a bunch of foreign Planet Eaters, in cahoots with their cronies in Lima, storming into the natives’ ancestral forest homes yet again to do what they please without consulting – or, more importantly, without financially rewarding – the folks who have lived there for 50,000 years. It’s just not the right thing to do. To be blunt but honest about it, what the natives are demanding – and rightfully so, after getting pushed out of the way and screwed over by the Planet Eaters for 500 years – is their rightful piece of the economic pie. What a concept! These guys actually want to get paid – and they’re not talking about some lousy beads and fish hooks, they’re talking about some good old American greenbacks. What gall, the greedy bastards!

I can already hear the howls of derision from the deluded tree-huggers reading these callous conclusions because – until I came down here to Peru and looked around with my own two eyes, and talked to a bunch of Amazon natives, and took the time to read the research and listen to the educated opinions of a lot of folks who know a elllot more about the subject than you and I will ever know – I was one of those deluded tree-huggers myself. After only two months in Peru – where I sit writing these words beside a waterfall on the banks of the Mother of God River in a ravaged rainforest cut down by the local natives themselves – I am still, more than ever, a tree-hugger… it’s just that I’m not quite so deluded as I was a couple of months ago.

Since the question on everyone’s lips is, obviously: “What do the natives who live inside the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve think about Hunt Oil’s plans to turn their ancestral home into an oilfield?,” that is the question I have spent the last six weeks asking people who know a lot more about the issue than I do, and have gotten a dozen different answers. I’m going to take the risk of oversimplifying this complicated issue by summarizing all these diverse opinions into one overview:

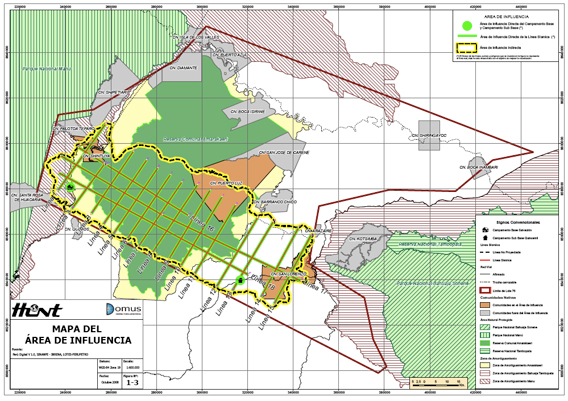

The biggest problem of all in gauging native resistance to Hunt Oil’s plans in Amarakaeri is that nobody knows for sure what the company wants to do here. Nobody even knows for sure whether they’re looking or oil, or gas, or both (Hunt is the major player in the ecological boondoggle know as the Camisea natural gas pipeline about 100 miles north of Amarakaeri). Hunt’s own laughable, predictable, fox-guarding-the-henhouse “environmental impact report” claims that, for now, they simply want to poke around in the woods to see if there’s anything of interest to them. Of course, this innocent-sounding “poking around in the woods” will involve – according to their own estimates – blazing some 300 miles of “seismic testing trails” through the trackless wilderness, detonating more than 12,000 explosive charges, and carving more than 100 helicopter landing pads out of the virgin rainforest. You don’t have to be Nostradamus to predict that, after spending that kind of dough, that of course they’re going to want to punch a couple of “test wells” into the ground to see if anything interesting bubbles up.

Deforestation from the Transcoeanic highway and gold mining activities on the Rio Huaypetue are clearly visible. |

The second biggest problem in gauging native resistance to Hunt Oil’s plans is that Amazon natives – like anyone else on the planet – have free will; ask the 2,000 or so natives in Amarakaeri what they think, and you’ll no doubt get 2,000 answers. Again, at the risk of oversimplification, here’s how I would characterize it:

The wild heart of Amarakaeri – Ground Zero where Hunt wants to go hunting – is ringed by eight “native communities,” comprised of three (not very communal) tribes. These eight villages, each represented by a “headman,” form a loose-knit association. Last time the association was polled (a few months before Bagua became the biggest story in the country and galvanized Amazon native opinion against Big Oil), the headmen were already unanimously opposed to any and all exploratory activity within their villages – the classic NIMBY (not-in-my-backyard) response..

Of course, if you look at Hunt’s own maps, you will notice that their exploration zone doesn’t even touch five of the eight communities; even the remaining three villages (which have already suffered extensive environmental damage, much of it inflicted by the natives themselves) are on the outer periphery of Hunt’s obvious “real” bulls-eye: the rich bio-diversity hotspot of the “communal” part of the communal reserve (though the engineers need the seismic data from the three villages to get a clearer picture of the potential oil pools under that target). As much as Hunt “needs” that seismic data, they could “compromise” with the natives by “pulling out” of the three villages, and it would barely affect their bottom line. Obviously, it will be easier for Hunt to buy off the natives’ acquiescence – whether through job offers, financial infusions into local schools and clinics, or outright offers of cold hard cash – than it would be to stir up the potential hornets’ nests of the communities themselves by bullying their way in. That is, in fact, my crystal-ball prediction of exactly how the game will play out, too.

Sadly, I’m left with the doom-n-gloomy conclusion that – if Hunt has the brains to show any restraint and class when dealing with the locals – they’re going to “win,” and the tree-huggers won’t be able to count on the local natives to back them up (especially in the “back woods” of the reserve, which is really what this fight is all about), despite centuries of evidence that the Planet Eaters’ intentions in the Amazon have historically been anything but benign. The lure of the almighty American dollar – and the plastic baubles it can buy folks who feel like they’ve been short-changed in the plastic-bauble department for way too long – will simply be too great of a temptation for them to resist. It’ll be a few temporary jobs instead of beads, but it’s just the latest version of the “man” moving in, pushing the Indians out of the way, wreaking havoc in the forest and in the culture, then abandoning them to deal with the mess when they’ve gotten what they came for. Will we ever learn?

View Larger Map. Oil exploration will shortly commence in this area. A shape file detailing the Block 76 should be available shortly.

One of the few “official sources” of written information I’ve been able to dig up is the approved 2006 edition of the “Amarakaeri Communal Reserve Master Plan” (which expires in 2012). To this day, I am not clear on exactly who the author is of this schizophrenic report. Opening the report, the first thing attracting my attention were the various maps of the reserve, particularly the “cultural history” map: sitting right there in the middle of Hunt Oil’s hopeful oil field for all the world to see, like a plump jackrabbit in a field of hungry coyotes, was a little mark that looked strangely like the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, DC. Looking up the symbol on the key, I read the words “Restos Arqueologicos indentificado por la CN Boca Ishirihue”—in other words, there appeared to be some largely unknown and unexplored Inca ruins in the middle of the very jungle where Hunt wants to blow off 12,000 explosives. Hmmm, I thought to myself, my little tree-hugging brain clicking away… I wonder if there could be anything to this.

Besides pricking my latent Indiana Jones nerve, the (easily discovered) news of these ruins aroused my suspicions because, just the day before, I had read the 67-page executive summary of Hunt’s “environmental impact report” (prepared by a Peruvian outfit called Domus Environmental Consultants and published in December, 2008). There, plainly stated on page 37, were the words:

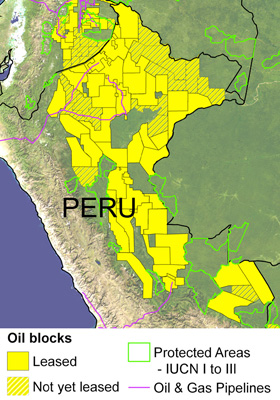

Oil and gas blocks in the western Amazon. Solid yellow indicates blocks already leased out to companies. Hashed yellow indicates proposed blocks or blocks still in the negotiation phase. Protected areas shown are those considered strictly protected by the IUCN (categories I to III). Image modified from Finer M, Jenkins CN, Pimm SL, Keane B, Ross C, 2008 Oil and Gas Projects in the Western Amazon: Threats to Wilderness, Biodiversity, and Indigenous Peoples. PLoS ONE 3(8): e2932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002932 |

“During the field evaluation, no evidence was found of archeological remains in the areas destined as Base and Sub-base Camps. On the other hand, it has not been possible to execute the archeological research along the 18 proposed lines. Nevertheless, in the revised areas, no archeological remains were identified; therefore, there is a favorable opinion for the execution of the works of the 2D seismic prospecting of Block 76, while installing a permanent archeological monitoring plan during the execution of the proposed works. The paperwork for the authorization to obtain the certificate of the “non-existence of archeological remains” is on its way.” (I’ve been unable to determine if Hunt was ever granted this “certificate” stating that no archaeological sites exist in Amarakaeri or whether they’re still waiting for it.)

You do not need to be Einstein to figure out that one of two things is true about this discrepancy: either Hunt/Domus knew damn well about these ruins and was hoping that nobody like me would come along to “discover” them in about 30 seconds of perusing a three-year-old public document; or Hunt/Domus, in its “exhaustive” search of impacts from its project, failed to turn them up. Giving them the benefit of the doubt that it was the second, it begs the question of what else they missed in a million acres of pristine rainforest if they’re too blind to see a set of ruins drawn in on a map of the reserve they’re studying so thoroughly.

It’s all a moot point now, anyway, because I’m 100 percent sure that Hunt knows about these ruins today, on the eve of destruction, because I’ve seen them drawn in right there on Hunt’s big wall map in their office in Salvacion. They’re right there near the intersection of Seismic Line 18 and 8, where sticks of dynamite will be blown off every 60 feet in the next few weeks. So, if Hunt has received their “certificate of the non-existence of archaeological ruins,” I would say that’s clearly a bogus document. (If anybody reading this knows any archaeologists who would be interested in this information, please forward it along to them and have them contact me for more information.)

Hunt Oil’s exploration zone (High resolution PDF).  Hunt Oil’s exploration zone (KML for Google Earth).

|

Next I turned to the short – and I mean short – discussion of potential hydrocarbon development in the reserve, and read this classic display of bureaucratic gobbledygook and doublespeak:

“During the elaboration process of the Master Plan for the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve, it was determined that hydrocarbon activity is currently not a threat to the natural protected area, as it is currently not practiced [Planet Eaters and tree-huggers alike can’t argue with that logic]; nevertheless, if this activity was carried out in the area without respecting the current legal basis, this would signify a threat [italics mine] to the objectives of creation of the Communal Reserve and its buffer zone.”

From there, the report goes on to document a long list of reasons why history has shown that projects such as the one Hunt is proposing aren’t a defensible use of environmentally sensitive areas such as Amarakaeri. To quote the report further:

“The experiences in the system of natural areas protected by the State and the experiences of native and farming communities located in those areas, related to hydrocarbon activities, are not very encouraging. We have for example a first case with Block 8 located in the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve, where a series of unfriendly environmental impacts occurred due to bad practices, like for example the sinking of a ship where no less than 6000 barrels of crude were spilled into the waters of the Maranon river, badly affecting the health of the Achuar ethnic group in the area and hundreds of acres of floodplain forest, where highly sensitive and biologically rich habitats were affected. A second case occurred in the buffer zone of the Titicaca National Reserve, where…there is a great environmental impact due to chemical contamination with formation waters, crude petrol, minerals and other toxic substances coming from inappropriately sealed oil exploration wells, that spill directly into Lake Titicaca… Due to these previous negative experiences and due to the very nature of hydrocarbon activity, this one seems to be a potential threat [italics mine] to the objectives of the creation of this natural protected area, its buffer zone and the local people…”

Then, suddenly, the “report” takes a turn toward the truly bizarre and starts smelling strongly of greased palm:

Courtesy of La Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri |

“On the other hand, hydrocarbon activity could be identified as an opportunity for an appropriate management of the Amarakaeri Communal Reserve. This is proven in cases like the one of Peru LNG (where Hunt Oil holds a 50 percent stake) and its work in Block 56 which contributed to the gathering, systemizing and publishing of primary biological information in the Machiguenga Communal Reserve [of course, the cursed Camisea Pipeline this is referring to also contributed to serious and widespread destruction of the area, though this little detail is conveniently ignored by the report’s enigmatic author].

“Actions like these… show that currently hydrocarbon industry… can be developed, given that the established laws and rules be respected, given that the management is carried out under the current international standards, and that in the exploration and exploitation phases the latest technologies and personnel highly specialized in hydrocarbon activity be employed, and above all that there be the environmental commitment on the companies’ side in order to avoid or minimize the environmental impacts inside the natural protected area and its buffer zone.” This laundry list of pie-in-the-sky, quicksand-firm “givens” is, of course, the grist of tree-huggers’ nightmares.

The bottom line of this suspicious “official” sell-out of this fragile million acres of pristine rainforest to Big Oil is this: “the National Institute for Natural Resources [essentially, the Peruvian version of the U.S. Forest Service] will be respectful of the contract between the government and the company inside the protected area.”

It just can’t get any clearer than that.

Related articles

Peru revokes decrees that sparked Amazon Indian uprising

(06/19/2009) Peru’s Congress revoked two controversial land laws that sparked violent conflicts between indigenous protesters and police in the country’s Amazon region. The move temporarily defuses a two-week crisis, with protesters agreeing to stand down by removing blockades from roads and rivers. Congress voted 82-14 Thursday to overturn legislative decrees 1090 and 1064, which would have facilitated foreign development of Amazon land. Indigenous groups said the decrees threatened millions of hectares of Amazon rainforest and undermined their traditional land use rights.

Peru suspends decree that triggered bloody conflict between Indians and police

(06/11/2009) Peruvian lawmakers yesterday suspended a controversial decree that contributed to a bloody conflict between police and indigenous protesters in the country’s Amazon region, reports the AFP.

(06/06/2009) More than 70% of the Peruvian Amazon has been allocated for oil and gas extraction, and the current government of Alan Garcia has been pushing for more. Unfortunately, as usual, these policies are promoted by and only benefit a handful of people, but negatively impact the lives of many. However, Garcia’s government did not foresee the potential consequences of their actions.

Peruvian police kill 10 Indians in battle over Amazon oil drilling

(06/06/2009) At least 30 are dead following a clash between police and Indians protesting oil development in Peru’s Amazon region.

Tribes in Peru to get $0.68/acre for protecting Amazon forest

(06/03/2009) Indigenous communities in Peru will be paid 5 soles ($1.70) per hectare ($0.68/acre) of preserved forest under a new conservation plan proposed by Peru’s Ministry of Environment, reports the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) in its bi-monthly update.

Peru may take military action against Indians protesting Amazon energy development

(05/19/2009) Indigenous protesters have stepped up demonstrations over the Peruvian government’s moves to support energy development in the Amazon rainforest, reports Reuters.

Peru’s uncontacted Amazon tribes under attack

(10/22/2008) Illegal logging in the Peruvian Amazon is driving uncontacted tribes into Brazil where they are in conflict over food and resources with other uncontacted groups, according to a Reuters interview with a leading expert on indigenous tribes.

Indian protesters win land rights battle against Peru’s President Garcia

(08/31/2008) Peru’s Congress rejected two decrees by President Alan García that made it easier for foreign developers to buy Amazon rainforest land. The repeal came just two days after lawmakers struck a deal with indigenous rights groups whose protests over the law had shut down oil and gas operations. The groups were worried that the laws weakened their land rights in favor of loggers, miners, and drillers.

In Peru, a showdown between the president and tribes over mining and drilling in the Amazon

(08/21/2008) In Peru indigenous rights groups and congressional leaders are pairing up against President Alan Garcia to revoke a controversial land law passed last week, reports Reuters.

Oil development could destroy the most biodiverse part of the Amazon

(08/12/2008) 688,000 square kilometers (170 million acres) of the western Amazon is under concession for oil and gas development, according to a new study published in the August 13 edition of the open-access journal PLoS ONE. The results suggest the region, which is considered by scientists to be the most biodiverse on the planet and is home to some of the world’s last uncontacted indigenous groups, is at great risk of environmental degradation.