|

|

Pesticides used by farmers in California’s Central Valley could be killing frogs in the Sierra mountains, report researchers.

Don Sparling of Southern Illinois University Carbondale found that minute quantities of endosulfan — the active ingredient in many pesticides — was enough kill frogs.

“At 0.8 parts per billion, we lose all of them,” Sparling said. 8 parts per billion is the equivalent of a dozen salt grains dissolved in 500 gallons of water.

“We always thought there was an association between pesticides and declining amphibian populations, and we’re building up a body of evidence to show this is the case.”

Sparling and colleagues found that endosulfan are making their way, likely via wind currents, into critical frog habitat, triggering die-offs among Pacific tree frogs and foothill yellow-legged frogs, which are native to meadows in California’s Sierra Mountains.

Pacific tree frog. Photo by Nancy Butler |

“The Central Valley is an extremely intense agriculture area, with everything from grapes to peaches, to nuts and tomatoes grown there,” Sparling explained. “Along with that, you have literally hundreds of thousands of pounds of active-ingredient pesticides, this is before it’s diluted, applied each year in this area.”

“These pesticides are applied by airplanes and we found that the wind would blow some of it up into the mountains, for instance. In other cases, these chemicals would volatize after being applied, turning into a gaseous state, which could also be picked up and spread into the mountains by wind.”

Sparling said that timing of pesticide application is also a factor.

Pesticides applied in late winter and early spring would end up in snow, which when melted would release the chemicals into the streams just as frogs begin to breed.

“As soon as ice is out of those streams, frogs start breeding,” Sparling said. “The newly hatched frog larvae are at their most vulnerable right at this time, when the chemicals are getting into the water.”

In addition to direct killing of frogs, Sparling says chemicals may have sub-lethal effects, triggering deformities that reduce survival rates.

“The sub-lethal effects of chemicals are probably even more important than outright killing,” he said. “It’s more insidious.”

Sparling says that the foothill yellow-legged frog is especially vulnerable to endosulfans and related chemicals, which are currently being evaluated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Europe and Australia have already banned use of the chemical as a pesticide.

“To produce crops to provide for the world we have to use pesticides, and I’m not anti-pesticide,” he said. “But it’s important for us as scientists, agriculturalists and environmental protectors to make sure we continue developing pesticides that are as protective as possible of non-target animals as can be, both in the chemicals we use and application methods.”

Sparling adds that monitoring of frog health can benefit people by alerting about potential environmental dangers.

“Frogs are like the canary in the coal mine. They serve as early alarms for the environment,” Sparling said. “They also provide a large and important link between the aquatic and terrestrial environments. If amphibians go, a huge link will be gone.”

Click to enlarge |

The link between pesticides and declining amphibian populations in mountainous areas has been suggested elsewhere. In January 2007 a study led by Frank Wania of the University of Toronto found that pesticides used in lowland areas in Central America are carried by air currents to higher elevations where they are they precipitated out as rain when the air cools. The chemicals — especially the insecticide endosulfan and fungicide chlorothalonil — then accumulate in the montane ecosystems, which have experienced particularly severe declines in amphibian populations over the past thirty years. Meanwhile other research has linked Atrazine, one of the most widely used pesticides in the United States, to dying salamanders.

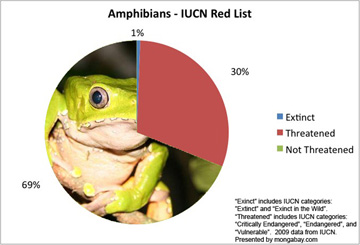

Amphibians face a barrage of threats beyond the effects of pesticide use including other forms of pollution, the introduction of alien species, habitat destruction, overcomsuption by humans, an outbreak of a deadly fungal disease, and climate change. According to the Global Amphibian Assessment, a comprehensive survey of the world’s 6,000 known species of frogs, toads, salamanders, newts and caecilians, about one-third of amphibians are classified as threatened with extinction.