Ecuador’s Chocó, under siege, but hope remains:

An interview with UCLA conservationist Dr. Jordan Karubian

mongabay.com

October 9, 2008

|

|

The Chocó, a region of humid tropical forest in western Colombia and northwestern Ecuador, is one of the world's biodiversity hotspots with high levels of endemic species but large-scale habitat loss. The situation is particularly dire in Ecuador where more than 90 percent of the Chocó has been cleared for agriculture. But hope is not lost. A dedicated team of researchers is working with local communities to ensure that Chocó will be around for future generations.

The Center for Tropical Research (CTR), a research and conservation group based at UCLA's Institute of the Environment, runs a program that combines research, training, education and grassroots sustainable development to conserve and expand Ecuador's endangered Chocó forests. The project, headed by Dr. Jordan Karubian, is improving rural livelihoods, preserving biodiversity and helping slow the country's deforestation rate, which is one of the highest in Latin America.

In an October 2008 interview with mongabay.com, Karubian discussed the project and its implications for conservation in Ecuador. A 5-minute overview of the project is also available in English and Spanish

AN INTERVIEW WITH JORDAN KARUBIAN

Mongabay: What is the Chocó and why is it a global priority for conservation?

The Chocó extends from southern Panama to western Colombia and northwestern Ecuador. All photos courtesy of CTR |

Jordan Karubian: The Chocó Biogeographical Region spans 100,000 square kilometers of humid forest in western Colombia and northwestern Ecuador. It is one of Conservation International's original 17 'Conservation Hotspots' and is among the 5% top areas in the world in terms of biodiversity, endemism (when species which occur in only one habitat type – in this case, the Chocó — and nowhere else in the world) and threat. For example, the Chocó is home to over 60 endemic species of bird, the highest number in the Americas (and over 500 species of bird total), yet only 5-10% of Ecuador's original Chocó forest remains. Worryingly deforestation continues at a steady pace. In Ecuador, deforestation is driven mostly by an impoverished local populace that lacks alternatives and depends on exploitation of natural resources through activities such as slash-and-burn agriculture, timber extraction, and hunting. Without active conservation efforts remaining Chocó forests will be lost in the near future, with a huge loss to biodiversity and to the well being of local residents.

Mongabay: What is the Center for Tropical Research (CTR) and what is its role in the Chocó?

|

Jordan Karubian: The Center for Tropical Research (CTR) is a research and conservation group based at UCLA's Institute of the Environment. Our over-arching goal is to understand the biotic processes that underlie and maintain the diversity of life and to advance conservation efforts that protect these processes. A focal point for CTR's work is Latin America, especially the mega-diverse country of Ecuador. Since 2002, as Latin America Director I have led a program focused on these highly threatened forests. Our project combines research, training, education and grassroots sustainable development to successfully conserve endangered species, slow global warming, reforest key areas, and improve the well being of local residents in critical rain forest habitat. Our work has been supported by the National Science Foundation, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, National Geographic Society, and Wildlife Conservation Society and has won the prestigious “Local Conservation Hero Award” from the Disney Wildlife Conservation Fund.

|

More generally speaking, CTR consists of a large network of senior scientists, postdoctoral researchers, and graduate students from a variety of disciplines and is led by UCLA professor Dr. Thomas B. Smith. CTR conducts research on many critical topics such as the processes which generate diversity in rainforests; the relationship between ecology and disease; habitat connectivity and conservation of migratory birds; and rainforest restoration in human-dominated landscapes. It also provides important training opportunities for young scientists and decision-makers from many countries Latin America, Australasia and Africa.

Mongabay: Who are the individuals involved in CTR's Chocó Project?

Jordan Karubian: Besides myself, CTR has involves researchers who have developed strong relationships with local stakeholders.

Jordan Karubian holding an Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis), one of the more than 500 species of birds that live in the Chocó rainforests |

Project Coordinator Dr. Renata Duraes is a Brazilian biologist with extensive Neotropical experience to help guide our expansion. She has published over 20 peer reviewed scientific articles and has conducted research and conservation work in Ecuador for over five years. Dr. Karubian and Duraes work closely with UCLA professor and Center for Tropical Research Director Dr. Thomas Smith, a recognized leader in tropical conservation efforts who played a key role in initiating this project and has been critical to its success. We also collaborate directly with UCLA professors Dr. Victoria Sork and Dr. Gregory Grether, both of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. In Ecuador, we employ a full-time team of local residents, university students and professional biologists, educators and agricultural experts.

In Ecuador, our work is led by In-county Director Mr. Luis Carrasco, a former honors thesis student who has been directing our work since 2006. He is assisted by Director of Scientific Research, Mr. Patricio Mena, another former university student, Education Director Ms. Monica Gonzalez, and sustainable agriculture expert Mr. Vicente Azuelo. All are highly trained and together have over three dozen years of on-the-ground conserveration experience between them. We also work closely with five local residents to whom we provide full time employment as researchers and Environmental Ambassadors: Mr. Jorge Olivo, Mr. Domingo Cabrera, Mr. Fernando Castillo, Mrs. Rosa Jaramillo, and Ms. Jaqueline Cabrera.

On the national level, we have close collaborations with Dr. David Romo and Dr. Kelly Swing from Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Dr. Carlos Ceron from Universidad Central, and Dr. Luis Albuja of the Instituto de Ciencias Biologicas de la Escuela Politecnica Nacional. We also work closely with Mr. Abel Olaya of the Ecuadorian Ministry of the Environment and Dr. Ivan Murillo, Director of the Jatun Sacha Foundation. These are all leading researchers and conservation practioners in Ecuador.

Mongabay: How did the Chocó Project start?

Dr. Jordan Karubian |

Jordan Karubian: After finishing my Ph.D. at the University of Chicago I went to UCLA as a post-doctoral fellow to develop scientific research with conservation implications in Latin America. I started doing this in a traditional, academic-minded way, but very soon realized the extent of the disconnect between the scientific community and the local reality. I soon moved to Ecuador, where I lived for four years, working closely with local residents to start a conservation and research project that was deeply in touch with the realities of the area. This project is now in its 6th year and has as mission to combine top-level, multidisciplinary scientific research with on-the-ground training, education, and sustainable development to achieve lasting conservation.

Mongabay: How well protected are the conservation areas in the Ecuadorean Chocó?

Jordan Karubian: Most of the protected areas in Ecuador are in the Amazon, the Andes, and the Galapagos Islands. Despite being over 90% deforested already, the Chocó region currently has only four major protected areas. As is common many parts of Latin America and the developing world in general, many of these areas are protected only on paper due to a lack of resources needed to implement regulations.

Mongabay: What are some of the noteworthy inhabitants of these forests?

A male of the Long-wattled Umbrellabird (Cephalopterus penduliger), a species that only occurs in the Chocó |

Jordan Karubian: The Chocó is one of the top global biodiversity hotspots, and a large proportion of the species inhabiting the Chocó are endemic, meaning that they are found nowhere else in the world. A major objective of our project is to develop scientific research on endemic and endangered Chocó species like the Long-wattled Umbrellabird (Cephalopterus penduliger). This large bird got its name because of its head feathers, which resemble an Elvis Presley hair-do that can be opened like an umbrella surrounding the bird's head in all directions. The second half of the name comes from another strange characteristic, the long wattle that hangs from the neck of the bird. This is a fleshy appendage covered in feathers that looks like a long, black tie and it is used for males during their exotic sexual courtship. These birds are endangered due to habitat loss, and their extinction would not only mean the loss of a very interesting-looking animal, but also a disruption for the forest dynamics. This is because Umbrellabirds are one of the few birds large enough to disperse big seeds that are typical of mature forests. Some other endemic Chocó species that are the focus of our research are the Banded Ground-Cuckoo (Neomorphus radiolosus) and the Brown Wood-rail (Aramides wolfi).

Mongabay: What does your research tell you about the overall health/status of the ecosystem?

Jordan Karubian: We conduct scientific research on three main fronts:

Some examples of animals that inhabit the Chocó |

Patterns of biodiversity in the Chocó: we investigate patterns of diversity of birds, reptiles, amphibians, insects and plants in relation to habitat types, in order to assess the effect different land use practices have on these organisms. Our results indicate, e.g., that forest that has been logged selectively for large trees harbors, after regeneration, a fauna that is very similar to that found in primary forest. Forest that was cleared, on the other hand, regenerates to a different climax stage and harbors different communities of animals.

Biology and basic life requirements of endemic bird species: our studies describe the basic biology of several bird species that are endemic to the Chocó and endangered of extinction, such as the Long-wattled Umbrellabird, the Ground Cuckoo, and the Brown Wood-rail. These birds were virtually unknown prior to our studies, and we have described the first nest known to science for each of these species and their basic biology, home range size, and habitat requirements. These are essential information for any future plans that aim to protect these species. For example, our studies show that some of these species avoid secondary forest (Banded Ground-Cuckoo), some can cross pastures but need mature forest to establish territories (the Long-wattled Umbrellabird), while others seem to be more resistant to forest alteration (Brown Wood-rail). All of them, however, are extremely dependent on forest habitats and will be definitely extirpated if deforestation continues at the current pace.

|

Investigating key ecosystem processes such as seed dispersal: by following animals with radio-transmitters and using molecular techniques to find out from which tree a seed came from, we are investigating the role some of the frugivorous species that are endemic to the Chocó have in dispersing seeds and thus maintaining the forest. We found out that the Long-wattled Umbrellabird is a key disperser for some large-seeded tree species that are typical of the mature forest. Long-wattled Umbrellabirds are extremely dependent on mature forest for their survivorship, but they can also fly long distances, often across open pastures, and likely have an important role for forest regeneration.

Mongabay: Who lives in the Chocó? Are there indigenous groups or is most of the population made of migrants from other parts of the country?

Jordan Karubian: Both. The Ecuadorian Chocó is home of tens of thousands of people from a rich cultural heritage, including people of indigenous, African and mestizo descent. In the area where our work is centred, the Mache-Chindul reserve, most residents are recent colonists (less than 20 years) coming from other parts of the country that have been altered to a point that they cannot sustain large rural human settlements any longer, but we also work closely with Chachi and Afro-Ecuadorian communities.

Mongabay: Local outreach and education seem to be an important part of your efforts to promote conservation. Can you elaborate on these programs?

An education program is leaded by Monica Gonzalez (in pink shirt) and reaches >1000 children and adults each year |

Jordan Karubian: We strongly believe that any conservation plan that aims to be long-lasting needs to include and involve local people. Based on this premise, our project seeks to engage local residents on both scientific and social levels. We train and employ local community members and university-level students as field biologists and environmental ambassadors. These individuals not only gather biological data that support our scientific research in the area, but also make regular presentations both in scientific meetings and at community gatherings to propagate our conservationist message. We also train and offer research opportunities to a number of biology students from both Ecuador and abroad. In addition, we hold a education program that is now in its fourth year and reaches >1000 children, adults and teachers in 15 communities. Finally, we are working to establish viable alternatives to deforestation. Our efforts right now are concentrated in the production of sustainable cacao, the raw material for chocolate. Our long term goal is a management plan for the area that is formulated by, agreed upon, and implemented by the local population.

Mongabay: You hire locals as research assistants. Do these Ecuadorians have opportunities to pursue higher education? Does their training give them opportunities to become wildlife guides and earn other sources of income?

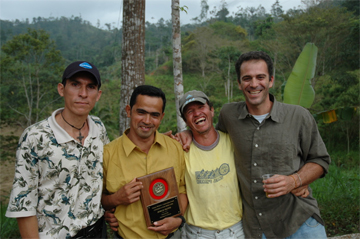

Jorge Olivo (second from left) was awarded the Disney Conservation Fund’s Conservation Hero Award in 2004 |

Jordan Karubian: The local residents that are trained and hired as field biologists in our project usually have the equivalent to an elementary school degree. Education is very limited in this area in general, and individuals with higher education is a rarity. We make our wages competitive, thus providing a direct economic incentive to these individuals to be environmentally-friendly. In recognition to his performance within our project, Mr. Jorge Olivo was awarded the Disney Wildlife Conservation Fund's “Local Conservation Hero Award” for 2006. All of our field biologists have by now presented the fruit of their efforts in the form of presentations at scientific meetings, which are attended by professionals of all Ecuador and abroad. Motivated by his participation in our project, Mr. Fernando Castillo, who is in his late 20s and had stopped his education when he graduated in high school, has recently decided to pursue a college degree in Biology. He has taken an entrance examination and has applied for a scholarship.

Mongabay: Is there potential for ecotourism to help contribute to local economic activity?

Jordan Karubian: Definitely. After all, this is a luscious rain forest full of fascinating animals and plants. There is much potential, and we are seeking to promote as much responsible tourism as possible.

Mongabay: Is there much potential for reforestation?

Outreach to local schools and communities is a central part of the project |

Jordan Karubian: Yes. The value of regenerating forests should not be underestimated. Given the right conditions, tropical forests regenerate relatively fast. In fact, reforestation is a main focus at Bilsa Biological Reserve, where much of our work is based. Bilsa is a 3,500-ha private reserve owned and operated by Fundación Jatun Sacha and located within the larger Mache-Chindul Reserve (~120,000 ha) in the Esmeraldas Province of Ecuador. In addition, we fostered the formation of a environmental network formed by local community members, and this group identified reforestation of watersheds as one of the top priorities in the area. Responding to this, the focus of this year's education program is forest regeneration and reforestation. We also received a grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services that will be partly directed to reforestation activities.

Mongabay: What is your outlook for the Ecuadorean Chocó over the next 20 years or so?

Slash-and-burn agriculture and pasture opening are main drivers of deforestation in the region |

Jordan Karubian: The situation in the Ecuadorian Chocó is critical, but we are optimistic. Our work has been highly successful to date, and we are now in the position to make a significant impact on the way things play out in this area. We have established models for successful research, education, training and development that can be exported to other sites in the region and further afield. We have established strategic alliances with Ecuadorian universities, the Ministry of the Environment, and key non-governmental organizations. And, most importantly, we have won the goodwill and trust of local residents: most local residents want to conserve but need our help to pursue viable alternatives to deforestation. There is tremendous potential, need and local desire to expand our project.

Mongabay: How can people in the U.S. help?

Jordan Karubian: Our project is funded 100% by grants and donations, and funding is a constant struggle to keep it up and running. Thus, the obvious way to help is to make a donation. Even a small amount can go a long ways in this impoverished area. If you would like to make a tax-deductible donation, please visit us online and be sure to note that the donation is for the Ecuador project

Mongabay: How would interested students apply to join the program?

Jordan Karubian: Just contact us – and non-students are welcome to apply as well!!!

- Project 5 min video (english)

- Project 5 min video (spanish)

- Project homepage

- Karubian homepage

- Institute of the Environment homepage

- Center for Tropical Research homepage