Researchers devise new comparison of mass extinction events

Researchers devise new comparison of mass extinction events

mongabay.com

September 2, 2008

|

|

Researchers have created a new way to compare historical mass extinction events.

The scoring system, presented in the early online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, works by multiplying the number of taxa — species, genera, and families — that went extinct by the inverse of the time it took to produce a measure dubbed “greatness”, which represents the magnitude of the event.

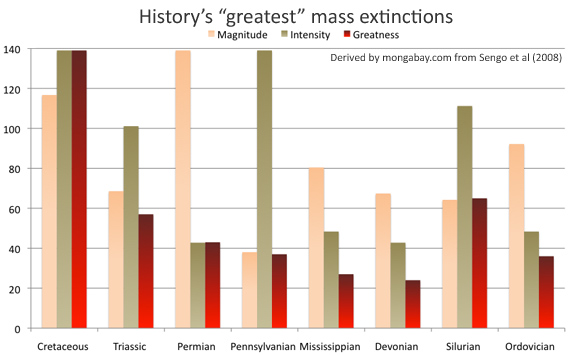

Using the system, Celâl Sengör and colleagues from Istanbul Teknik Üniversitesi of Turkey rank the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) event — when the dinosaurs were extinguished in a flash by an asteroid strike or mass oceanic poisoning by a spasm of volcanic activity — as the greatest mass extinction in history. The Permian, which featured a greater loss of species (90-95 percent of marine species and 70 percent of land species) but played out over a longer period to time some 250 million years ago, ranks third after the Silurian, which occurred around 440 million years ago. The Permian, Pennslyvanian, and Ordovician lag behind on their scale.

The “greatness” of an extinction is the product of its magnitude (i.e. biodiversity loss during the event) times the its intensity (the duration of the extinction event). Thus the red column is what researchers consider the most complete measure of extinction events.

The authors then attempt use the methodology to compare past mass extinctions to the current extinction event that scientists say is being driven by human activities, including habitat destruction, pollution, over-exploitation, introduction of alien species, and global warming. In the end they conclude that the present-day mass extinction — dubbed the Holocene extinction event — bears little resemblance toward any individual historical event, but shares characteristics of several and could someday prove to be the greatest event the planet has ever seen.

“The present extinction, which seems greater than any thus far, has elements of those of both the Cretaceous and Permian,” they write. “It represents a virtual Pangea formation by providing human-caused transfer of organisms world-wide simulating a world with no oceanic barriers, leading to increased competition without opening new niches and the introduction of a global annihilating agent, namely humans, that creates functional deserts for much of the rest of the biosphere (human dwellings) at a rate unknown in the history of the biosphere during the Phanerozoic. It is a Lyellian event accelerated and magnified to Cuvierian dimensions.”

“If unchecked, the present extinction threatens to be the greatest killer of all time,” the authors conclude.

A. M. Celâl Sengör, Saniye Atayman, and Sinan Özeren (2008). A scale of greatness and causal classification of mass extinctions: Implications for mechanisms. PNAS September 9, 2008 vol. 105 no. 36.

Global warming may cause biodiversity extinction

(3/21/2007) Extinction is a hotly debated, but poorly understood topic in science. The same goes for climate change. When scientists try to forecast the impact of global change on future biodiversity levels, the results are contentious, to say the least. While some argue that species have managed to survive worse climate change in the past and that current threats to biodiversity are overstated, many biologists say the impacts of climate change and resulting shifts in rainfall, temperature, sea levels, ecosystem composition, and food availability will have significant effects on global species richness.

|

Biodiversity extinction crisis looms says renowned biologist

(3/12/2007) While there is considerable debate over the scale at which biodiversity extinction is occurring, there is little doubt we are presently in an age where species loss is well above the established biological norm. Extinction has certainly occurred in the past, and in fact, it is the fate of all species, but today the rate appears to be at least 100 times the background rate of one species per million per year and may be headed towards a magnitude thousands of times greater. Few people know more about extinction than Dr. Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden. He is the author of hundreds of scientific papers and books, and has an encyclopedic list of achievements and accolades from a lifetime of biological research. These make him one of the world’s preeminent biodiversity experts. He is also extremely worried about the present biodiversity crisis, one that has been termed the sixth great extinction.

Extinction risk accelerated when interacting human threats interact

(2/7/2007) A new study warns that the simultaneous effect of habitat fragmentation, overexploitation, and climate warming could increase the risk of a species’ extinction.

|

Just how bad is the biodiversity extinction crisis?

(2/6/2007) In recent years, scientists have warned of a looming biodiversity extinction crisis, one that will rival or exceed the five historic mass extinctions that occurred millions of years ago. Unlike these past extinctions, which were variously the result of catastrophic climate change, extraterrestrial collisions, atmospheric poisoning, and hyperactive volcanism, the current extinction event is one of our own making, fueled mainly by habitat destruction and, to a lesser extent, over-exploitation of certain species. While few scientists doubt species extinction is occurring, the degree to which it will occur in the future has long been subject of debate in conservation literature. Looking solely at species loss resulting from tropical deforestation, some researchers have forecast extinction rates as high as 75 percent. Now a new paper, published in Biotropica, argues that the most dire of these projections may be overstated. Using models that show lower rates of forest loss based on slowing population growth and other factors, Joseph Wright from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama and Helene Muller-Landau from the University of Minnesota say that species loss may be more moderate than the commonly cited figures. While some scientists have criticized their work as “overly optimistic,” prominent biologists say that their research has ignited an important discussion and raises fundamental questions about future conservation priorities and research efforts. This could ultimately result in more effective strategies for conserving biological diversity, they say.