Future cities will be more like ecosystems that enrich society and the environment

Future cities will be more like ecosystems that enrich society and the environment

Tina Butler, mongabay.com

May 30, 2008

|

|

As The World Science Festival continues in New York this week, specialists in vastly diverse fields across scientific disciplines are coming together to talk about ideas, problems and solutions. From Astronomy to Bioacoustics, the dialogues about challenges and opportunities are rich and inspiring. At the front of this year’s festival rests the issue of sustainability and how scientists, specialists and society will address the imminent environmental and economic trials we are sure to face in a rapidly changing and uncertain world.

One such dialogue is taking place in the event, Future Cities: Sustainable Solutions, Radical Designs, where creative minds on the bleeding edge will push the boundaries and definitions of what the modern city can be—from vertical farms housed in high rises to stackable cars that fit together like airport luggage carts—and how future urbanites may live, work, travel and eat.

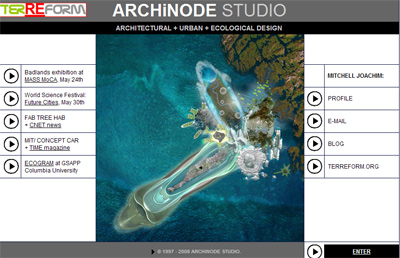

At the center of this conversation is Dr. Mitchell Joachim, an innovating architect and urban designer with a radical new vision for the urban sphere. Dr. Joachim is engaged in a number of organizations and projects that all seek to further an integration of ecological design principles into the human space. He won Time Magazine’s Best Invention of the Year in 2007 for his collaboration with the Smart Cities Group for the Compacted Car and is a partner in the nonprofit design organization Terreform as well as the mind behind the Fab Tree Hab project.

|

Dr. Joachim has a doctorate in architecture from MIT and master’s degrees from Harvard and Columbia in urban design and architecture. After working as an architect at Gehry Partners and Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, he is currently teaching at Columbia and Washington University in St. Louis.

Dr. Joachim took time earlier this week to discuss some of the challenges of increasing urbanization, population pressures and making the case for sustainability, as well as some of his upcoming projects.

Mongabay: What is the biggest problem facing cities today—the rapid influx of inhabitants, inefficiencies in existing infrastructure, lack of financial resources for improvements or some other issue?

Dr. Mitchell Joachim: In other words—what is key to keeping cities sustainable?

The key to being sustainable is by not being sustainable! For example- would you want your marriage/relationship to be “sustainable’? No, people desire to be evolving, growing, living, learning, etc., not just getting along for the next year. “Sustainability” as a term is not provocative enough for cities. At the urban scale we need to think about integrated and positive ecological solutions—solutions that fit holistically within the metabolism of urbanity. Imagine cars in our future city; how can they positively contribute to the local ecology? What kind of a car cleans the air and accounts for 50 years of industrial pollution? Today we mostly concentrate on cars in the city that are efficiency-based models. These do less damage than previous cars, but still continue to exacerbate the energy crisis. Neutral models are not much better. Neutral or zero emission vehicles do no further damage, but don’t alter the current condition positively. A positive ecological mobility system is the most provocative design goal for future cities. This means vehicles that are powered by renewable sources, add to the energy grid, possess intelligence, and scrub the atmosphere. Such as fuel cell vehicles with green hydrogen reformation.

see more on this theory called transology and eoctransology

People wonder if sustainability is affordable… our Fab Tree Hab project addresses this issue:

In departing from the modern sense of home construction, compilation of a budget for this living home prototype inherently opens the debate surrounding decision-making and green architecture. It is widely acknowledged that life-cycle costing methods would provide more favor to conscientious home designs by including energy cost savings and, more abstractly, accounting for reduction or elimination of externality costs. However, this falls short of recognizing the compound and continuous value of sustainable housing as an interweave of systems, and it still places too much value on benefits received today as opposed to tomorrow or hundred years from now. By rejecting the tendency towards immediacy, and, likewise, first cost dependency, a true representation of sustainable value can be achieved by explicitly recognizing the adaptive, renewal, cooperative, evolutionary, and longevity characteristics of the home. Our design explores the concepts in that debate by including all five traits.

Mongabay: With the urbanizing trend and mounting population pressures, what is the best strategy for integrating nature into the urban environment while meeting inhabitants’ housing, business and transportation needs?

Dr. Mitchell Joachim: We’re often told that today’s cities are “greener” than, say, suburbs in developed countries. This is the Sprawl vs Sprung debate: is it better to spring up tall densely compacted towers or spread out across virgin land? Most of this argument is too complex to discuss in a short answer. However, the transportation factor is a major consideration. US transport uses 29% of our total energy needs– this figure is expected to double in forty years. Public transit systems serving millions do greatly reduce the overall energy demand on cities. It is safe to say tooling around in cars in suburbia is wasteful. Can we do more? Yes: re-think mobility, especially form a life cycle perspective; design vehicles that “fit the city” instead of cities accommodating vehicles. Smart cars designed to move in flocks or herds, called “gentle congestion” is one such solution.

Mongabay: What kind of resistance might one of these projects face and from whom?

Dr. Mitchell Joachim: What is the cost of inaction? To what extent can cities be allowed to evolve organically, as opposed to needing the hand of planners? In the future, we won’t be around to discuss the cost of inaction. Planners, urban designers and architects don’t shape cities. They never really have. For instance, in the field of Urban Design, you can author the “design” elements but you can’t create the “urban” condition. Urbanity happens, with or without good planning and design. No single constituency is responsible for the making of our cities. The best hope for a practicing city designer is to evoke a riff or sensibility, not a script tomorrow.

Mongabay: What is your next project?

Dr. Mitchell Joachim: A full scale 3d print model of Manhattan made from materials found in Fresh Kills landfill. We calculate there is enough waste material to make five such prototypes.