Global warming solutions are hurting indigenous people, says U.N.

Global warming solutions are hurting indigenous people, says U.N.

mongabay.com

April 2, 2008

|

|

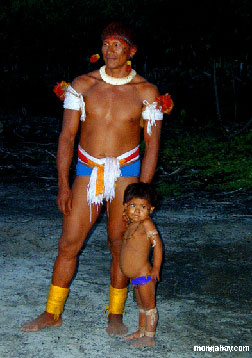

Large-scale solutions intended to help mitigate global warming are harming the very indigenous people who are likely to bear the brunt of climate change, warned the United Nations University (UNU) at a conference in Darwin, Australia.

Biofuel plantations, renewable energy projects like hydroelectric dams, and measures to protect forests as carbon sinks threaten to undermine rights of indigenous groups. Such initiatives boost the value of land and increase the likelihood that indigenous people will be displaced.

“Indigenous peoples regard themselves as the mercury in the world’s climate change barometer,” said UNU Director A.H. Zakri. “They have not benefited, in any significant manner, from climate change-related funding, whether for adaptation and mitigation, nor from emissions trading schemes. The mitigation measures for climate change are very much market-driven and the non-market measures have not been given much attention.”

|

Noting that there are at least 370 million indigenous people around the world living carbon neutral or carbon negative life styles, Zakri said that climate change presents these groups with rising sea levels; increased risk of diseases including cholera, malaria and dengue fever; higher incidence of drought and desertification; melting glaciers and thawing permafrost; greater food insecurity from coral bleaching and increasingly unpredictable growing seasons; increased likelihood of damage from invasive species; more extreme weather, including storms and hurricanes; and changes in the biodiversity on which they stake their livelihoods.

Controversy over carbon offsets for forest conservation

UNU highlighted controversy over the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)’s recent decision to include forestry as a way to offset greenhouse gas emissions. The mechanism, which has been hailed by scientists and environmentalists as a way to fund forest conservation while at the same time fighting climate change, was criticized in a paper by Estebancio Castro Diaz, a Kuna Indian from Panama who works for the Global Forest Coalition, a native peoples’ NGO.

“Despite recent developments in international law in relation to Indigenous Peoples rights, Indigenous Peoples still have limited or in some instances no participation in the decision-making processes of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),” wrote Diaz. “The UNFCCC instigated negotiations between Member Parties to explore ways and means to reduce emissions of deforestation and degradation in developing countries (REDD). These negotiations have taken place and continue to take place without any meaningful participation by Indigenous Peoples. Yet Indigenous Peoples rights and their experience in sustainable forest management mean that their participation in these fora is imperative, in the REDD discussions or any other discussions relating to environmental protection.”

|

Diaz said that without formal land rights, indigenous people may get left out of compensation schemes for environmental services provided by forests and other ecosystems. The U.N. estimates that the market for REDD alone could reach $100 billion.

Still some are hopeful that REDD could offer indigenous groups new ways to earn an income while allowing them to continue living in traditional ways should they so desire.

“The proposal to reduce emissions through deforestation and degradation (REDD), if done the right way, might be an opportunity to stop deforestation and reward indigenous peoples and other forest dwellers for conserving their forests,” wrote Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, an Igorot from the Philippines, and Aqqaluk Lynge, an Inuit from Greenland. “Indigenous agroforestry practices are generally sustainable, environmentally friendly, and carbon-neutral. When the Bank launched its Forest Carbon Partnership Facility in Bali, it received a lot of criticism from indigenous peoples, who had been excluded from the conceptualization process in spite of the fact that they are the main stakeholders where tropical and sub-tropical forests are concerned. To remedy this weakness, the World Bank will hold consultations with indigenous peoples from Asia, Latin America and Africa.”

Dr. Daniel Nepstad, a scientist at the Woods Hole Research Institute who works in the Amazon basin, said that indigenous groups must be fairly compensated for carbon offset initiatives to be successful. He cites the Xingu indigenous reserve in the heart of the agricultural frontier of the Brazilian Amazon as an example.

“Inside the Xingu indigenous reserve… Indians could really be seen as the guardians of the forest for keeping it standing against the economic interests. The state is supposed to take care of the reserve, but in fact the Indians do a perfect job in that region,” he told mongabay.com. “The Indians who live in the Xingu park need to be compensated. So that’s where REDD comes in.”

“A response to the protestors out in front of the World Bank in Bali… is look at the indigenous groups in the Amazon. They very much want REDD. They want to be at the table and negotiate REDD to make sure that they are not cut off from their forest resources.”

Renewable energy and biofuels

|

Participants in the UNU meeting said that booming interest in renewable energy has further marginalized indigenous populations. In Indonesia and Malaysia, forest people have been displaced by the rapid expansion of oil palm plantations, while groups in other parts of the world have lost land to dams, nuclear waste sites, and soy farms. Tauli-Corpuz and Aqqaluk Lynge added that the surging market for biofuels have driven up prices for food, making it more difficult for some indigenous populations to feed themselves.

Effcts of climate change on indigenous people

UNU included an overview a brief overview of the effects of climate change on indigenous people on a regional basis:

-

Africa

There are 2.5 million kilometers of dunes in southern Africa covered in vegetation and used for grazing. However the rise in temperatures and the expected dune expansion, along with increased wind speeds, will result in the region losing most of its vegetation cover and become less viable for indigenous peoples living in the region.

As their traditional resource base diminishes, traditional practices of cattle and goat farming will disappear. There are already areas where indigenous peoples are forced to live around government-drilled bores for water and depend on government support for their survival. Deteriorating food security is a major issue for indigenous peoples residing in these drylands.

Asia

In Asia’s tropical rainforests, a haven for biodiversity, as well as indigenous peoples’ cultural diversity, temperatures are expected to rise 2 to 8 degrees Celsius, rainfall may decrease, prompting crop failures and forest fires.

People in low-lying areas of Bangladesh could be displaced by a one-meter rise in sea levels. Such a rise could also threaten the coastal zones of Japan and China. The impact will mean that salt water could intrude on inland rivers, threatening some fresh water supplies.

In the Himalayas high altitude regions, glacial melts affect hundreds of millions of rural dwellers who depend on the seasonal flow of water. There might be more water short term but less long term as glaciers and snow cover shrink.

The poor, many of whom are indigenous peoples, are highly vulnerable to climate change in urban areas because of their limited access to profitable livelihood opportunities and will be exposed to more flood and other climate-related risks in areas where they are forced to live.

Central and South America and the Caribbean

This very diverse region ranges from the Chilean deserts to the tropical rainforests of Brazil and Ecuador, to the high altitudes of the Peruvian Andes.

As elsewhere, indigenous peoples’ use of biodiversity is central to environmental management and livelihoods. In the Andes, alpine warming and deforestation threaten access to plants and crops for food, medicine, grazing animals and hunting.

Earth’s warming surface is forcing indigenous peoples in this region to farm at higher altitudes to grow their staple crops, which adds to deforestation. Not only does this affect water sources and leads to soil erosion, it also has a cultural impact. The uprooting of Andean indigenous people to higher lands puts their cultural survival at risk.

In Ecuador, unexpected frosts and long droughts affect all farming activities. The older generation says they no longer know when to sow because rain does not come as expected. Migration offers one way out but represents a cultural threat.

In the Amazon, the effects of climate change will include deforestation and forest fragmentation and, as a result, more carbon released into the atmosphere, exacerbating climate change. The droughts of 2005 resulted in western Amazon fires, which are likely to recur as rainforest is replaced by savannas, severely affecting the livelihoods of the region’s indigenous peoples.

Coastal Caribbean communities are often the center of government activities, ports and international airports. Rapid and unplanned movements of rural and outer island indigenous residents to the major centers is underway, putting pressure on urban resources, creating social and economic stresses, and increasing vulnerability to hazardous weather conditions such as cyclones and diseases.

The relationship between climate change and water security will be a major issue in the Caribbean, where many countries are dependant on rainfall and groundwater.

Arctic

The polar regions are now experiencing some of Earth’s most rapid and severe climate change. Indigenous peoples, their culture and the whole ecosystem that they interact with is very much dependent on the cold and the extreme physical conditions of the Arctic region.

Indigenous peoples depend on polar bears, walrus, seals and caribou, herding reindeer, fishing and gathering not only for food and to support the local economy, but also as the basis for their cultural and social identity. Among concerns facing indigenous peoples: availability of traditional food sources, growing difficulty with weather prediction and travel safety in changing ice and weather conditions.

According to indigenous peoples, sea ice is less stable, unusual weather patterns are occurring, vegetation cover is changing, and particular animals are no longer found in traditional hunting areas. Local landscapes, seascapes and icescapes are becoming unfamiliar.

Peoples across the Arctic region report changes in the timing, length and character of the seasons, including more rain in autumn and winter and more extreme heat in summer. In several Alaskan villages, entire indigenous communities may have to relocate due to thawing permafrost and large waves slamming against the west and northern shores. Coastal indigenous communities are severely threatened by storm-related erosion due to melting sea ice. Up to 80% of Alaskan communities, comprised mainly of indigenous peoples, are vulnerable to either coastal or river erosion.

In Nunavut, elders can longer predict the weather using their traditional knowledge. Many important summer hunting grounds cannot be reached. Drying and smoking foods is more difficult due to summer heat undermining the storage of traditional foods for the winter.

In Finland, Norway and Sweden, rain and mild winter weather often prevents reindeer from accessing lichen, a vital food source, forcing many herders to feed their reindeer with fodder, which is expensive and not economically viable long term. For Saami communities, reindeers are vital to their culture, subsistence and economy.

Central and Eastern Europe, Russian Federation, Central Asia and Trans-Caucasia

Survival of indigenous peoples, who depend on fishing, hunting and agriculture, also depends on the success of their fragile environment and its resources. As bears and other wild game disappear, people in local villages will suffer particular hardships. Worse, unique indigenous cultures, traditions and languages will face major challenges maintaining their diversity.

Indigenous peoples have noticed the arrival of new plant species that thrive in rivers and lakes, including the small flowered duckweed which has made survival difficult for fish. New bird species have also arrived and birds now stay longer than before.

Changes in reindeer migration and foraging patterns, sparked by fluctuating weather patterns, cause problems also in this region, whose indigenous people have witnessed unpredictable and unstable weather and shorter winters.

North America

About 1.2 million North American tribal members live on or near reservations, and many pursue lifestyles with a mix of traditional subsistence activities and wage labour. Many reservation economies and budgets of indigenous governments depend heavily on agriculture, forest products and tourism.

Global warming is predicted to cause less snowfall and more droughts in many parts of North America, which will have a significant impact on indigenous peoples. Water resources and water quality may decrease while extended heat waves will increase evaporation and deplete underground water resources. There may be impacts on health, plant cover, wildlife populations, tribal water rights and individual agricultural operations, and a reduction of tribal services due to decrease in income from land leases.

Natural disasters such as blizzards, ice storms, floods, electric power outages, transportation problems, fuel depletion and food supply shortages will isolate indigenous communities.

Higher temperatures will result in the loss of native grass and medicinal plants, as well as erosion that allows the invasion of non-native plants. The zones of semi-arid and desert shrubs, cactus, and sagebrush will move northward. Finally, fire frequency could also increase with more fuel and lightning strikes, degrading the land and reducing regional bio-diversity.

Pacific

Most of the Pacific region comprises small island states affected by rising sea levels. Environmental changes are prominent on islands where volcanoes build and erode; coral atolls submerge and reappear and the islands’ biodiversity is in flux. The region has suffered extensively from human disasters such as nuclear testing, pollution, hazardous chemicals and wastes like Persistent Organic Pollutants, and solid waste management and disposal.

High tides flood causeways linking villages. This has been particularly noticeable in Kiribati and a number of other small Pacific island nations that could be submerged in this century.

Migration will become a major issue. For example, the people of Papua New Guinea’s Bougainville atoll island of Cartaret have asked to be moved to higher ground on the mainland. The people of Sikaiana Atoll in the Solomon Islands have been migrating primarily to Honiara, the capital. There has been internal migration from the outer islands of Tuvalu to the capital Funafuti. Almost half of Tuvalu’s population now resides on the Funafuti atoll, with negative environmental consequences, including increased demand on local resources.

Warmer temperatures have led to the bleaching of the Pacific Island ‘s main source of survival — the coral reefs. The algae that help feed coral is loosened and, because the algae give them colour, the starved corals look pale. Continued bleaching ultimately kills corals. Coral reefs are an important shelter for organisms and the reduction of reef-building corals is likely to have a major impact on biodiversity. Tropical fishery yields are on the decline worldwide and it is now clear that the conditions may become critical for the local fish population.

Agriculture in the Pacific region, especially in small island states, is becoming increasingly vulnerable due to heat stress on plants and saltwater incursions. Hence, food security is of great concern to the region.