Fatal San Diego Shark Attack a Rare Event

Fatal San Diego Shark Attack a Rare Event

mongabay.com

April 25, 2008

|

|

Friday morning a 66-year-old swimmer was attacked and killed by a shark off Solana Beach in San Diego county. It was the first fatal shark attack in San Diego since 1994.

According to the San Diego Union-Tribune, Friday’s shark attack took place about 150 yards offshore in Fletcher Cove, a popular swimming area. The victim, David Martin of Solana Beach, a member of the Triathlon Club of San Diego, a father of four, and a retired veterinarian, was swimming with a group of about 10 other swimmers in water 20 to 30 feet deep. The swimmers were wearing wetsuits.

Witnesses told lifeguards that a “big gray shark” attacked Martin, biting both his legs. The shark is believed to be a great white, the third largest species of shark and generally considered the most dangerous to humans.

Richard H. Rosenblatt, a professor emeritus of marine biology at Scripps Institution of Oceanography who examined Martin’s body, told the San Diego Union-Tribune he believed the shark measured 12- and 17-feet-long. Adolescent males are said to be the most likely to attack, mistaking humans for seals, their natural prey.

Witness accounts of the attack describe “typical… white shark feeding behavior,” Rosenblatt was quoted as saying. “They normally feed on seals and attack from below and … bite, then pull away and wait for the seal or other marine mammal to bleed to death.”

|

Shark attacks in perspective

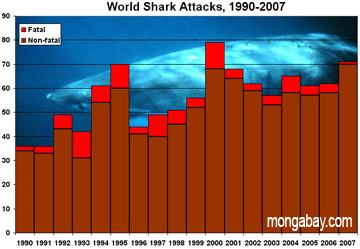

While the attack has received widespread media attention, fatal shark attacks are increasingly rare relative to the number of people participating in ocean activities. In 2007 human deaths from shark attacks hit a 20-year low, according to statistics released by the University of Florida.

The single death of a swimmer in the South Pacific in 2007 represented the fewest casualties from shark attacks since 1987, when no one was killed by sharks.

“It’s quite spectacular that for the hundreds of millions of people worldwide spending hundreds of millions of hours in the water in activities that are often very provocative to sharks, such as surfing, there is only one incident resulting in a fatality,” said George Burgess, director of the International Shark Attack File housed at UF’s Florida Museum of Natural History. “The danger of a shark attack stays in the forefront of our psyches because of it being drilled into our brain for the last 30 years by the popular media, movies, books and television, but in reality the chances of dying from one are infinitesimal.”

“Falling coconuts kill 150 people worldwide each year,” he added.

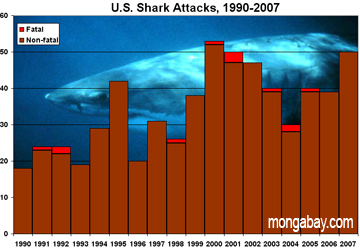

Generally roughly half of the world’s attacks occur in U.S. waters. 2007 saw 50 of the world’s 71 shark attacks occur in the United States.

Despite lower numbers of fatal attacks overall attacks have been rising over the past 4 years.

“One would expect there to be more shark attacks each year than the previous year simply because there are more people entering the water,” Burgess said. “For baby boomers and earlier generations, going to the beach was basically an exercise in working on your suntan where a swim often meant a quick dunking. Today people are engaged in surfing, diving, boogie boarding and other aquatic activities that put them much closer to sharks.”

Due to warm waters and the popularity of ocean activities, Florida led the world in shark attacks again in 2007 with 32. Hawaii was second with seven.

Fifty-six percent of the 2007 victims were surfers and wind surfers; followed by swimmers and waders, 38 percent; and divers and snorkelers, 6 percent.

Burgess said that advances in medical treatment, greater attention to beach safety practices and increased public awareness about the danger of shark attacks are likely reasons that fatalities from shark attacks continue to fall. At 7.6 percent, the shark attack fatality rate for the 21st century has been lower than the 12.3 percent recorded for the 1990s.

Overfishing has also diminished the abundance of larger shark species that are more likely to inflict life-threatening bites to humans.