Brazil prepares to launch attack on NGOs working in the Amazon

Brazil prepares to crackdown on foreign NGOs in the Amazon

mongabay.com

April 27, 2008

|

|

Brazil is planning a crackdown on foreign NGOs working in the Amazon rainforest, reports Reuters. Tourists may also be required to inform officials of their travel plans in the region under the newly proposed rule.

Claiming concerns over “sovereignty” and “biopiracy”, Justice Minister Tarso Genro told the media Wednesday that NGOs would have to get permissions from the Justice Ministry and register with the military if they wanted to operate in the region. Foreign visitors — including tourists according to Brazil’s National Justice Secretary Romeu Tuma — would be required to also get special permits for the Amazon.

The bill — on its way to the Brazilian Congress — would impose fines of 5,000 and 100,000 reais ($3,000 and $60,000) for visitors and organizations found to be working in the Amazon without official permission. Violators would also be subject to deportation.

|

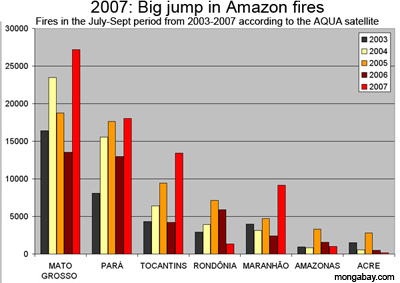

The news comes as Brazil faces increased criticism from NGOs over rising deforestation in the Amazon. Government figures are expected to show a doubling of deforestation to 7,000 square kilometers between August 2007 and the end of the year, according to environmental group Greenpeace. High commodity prices are fueling forest conversion.

Biopiracy claims an attempt to stifle criticism?

Brazil’s sensitivity over the Amazon and “biopiracy” are not new. In the late 1950s, following the internationalization of Antarctica, Brazil became concerned over its tenuous claim to the Amazon and began taking steps to assert control over the region. To establish a “presence” in the Amazon, and therefore the right to keep it as part of the national territory, the Brazilian government set up the Manaus Free Trade Zone — a sort of tariff-free manufacturing zone — and aggressively promoted settlement and development in the Amazon, resulting in widespread forest loss, especially in the 1970s and 1980s. Today Brazil frequently asserts its rights to develop the Amazon as it pleases. Congress has launched several investigations into alleged “biopiracy” by researchers in the Amazon but these have failed to turn up any evidence of wrong doing. Conspiracy theories aside, some researchers believe the investigations are merely a guise by development interests to stifle criticism and oppose conservation efforts in Earth’s biggest rainforest.

“Brazil has lost all kinds of money and intellectual importance because of its attempts to protect biodiversity from international interference,” Brazilian researcher Philip Fearnside of INPA told Nature, following a flap over the jailing of Dr. Marc Van Roosmalen, a prominent Brazilian primatologist and conservationist, last year. Van Roosmalen was later freed after international condemnation of the arrest and a call for strikes and civil disobedience by Brazilian scientists.

“Scientists worldwide consider Dr. van Roosmalen’s indictment and sentencing as an attack on the practice and profession of biological science in Brazil, and as an attack on individual scientists,” said a statement issued by the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC), a body of scientists, shortly after van Roosmalen’s incarceration. “At a time when ecological research is more critical than ever to enable the wise use and management of plants, animals and microbes in the world’s tropics, Dr. van Roosmalen’s indictment, trial, sentencing, incarceration and the associated media response is already discouraging biological research in Brazil, both by Brazilian scientists and by potential international collaborators. Dr. van Roosmalen’s situation is indicative of a trend of governmental repression of scientists in Brazil.”

|

“Van Roosmalen is a specific case, within a broader context that is very sad for the country,” Leandro Salles of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro was quoted as saying by Nature in the aftermath of the arrest. “Under the current laws, researchers are treated as potential criminals.”

Dr. Roberto Cavalcanti, a zoology professor at the University of Brasilia, told The Associated Press in 2005 that the “biopiracy concept ‘has been hijacked’ by opponents of measures to protect the rain forest against commercial overexploitation.”

Another scientist, who asked to remain anonymous, told mongabay.com: “If there has been serious biopiracy in Brazil ever, I would be curious to know about it.”

Even a member of an earlier congressional biopiracy committee has expressed skepticism over the efforts.

“Up to now, we haven’t found a single concrete case of biopiracy,” Congressman Jose Sarney Filho, a former environment minister, told The Associated Press in an interview in 2005. “There are cases of spiders being contrabanded to American laboratories and things like that, but no material proof that our flora or fauna has been converted into medicine without following the legislation.”

Some Brazilians cite the alleged theft of rubber seeds from Brazil in the 19th century as the crowning example of biopiracy from the country. Still, according to Wade Davis in his book One River, “all evidence” suggests that the exportation was sanctioned at the time by Brazilian authorities in Belèm.