Why there is still hope for conservation in the Philippines: A new paper explores the positive environmental trends in a ‘lost-cause’ nation

The Philippines has often been an example for the worst-case-scenario in environmental degradation. Some scientists have even concluded that environmental efforts should put elsewhere, claiming the Philippines to be a lost cause. In his book Requiem for Nature John Terborgh writes the “overpopulated… Philippines are already beyond the point of no return.” However, a recent paper entitled “Hope for Threatened Tropical Biodiversity: Lessons from the Philippines” argues that there are enough positive environmental and conservation trends in the Philippines to have hope and continue working for a better tomorrow.

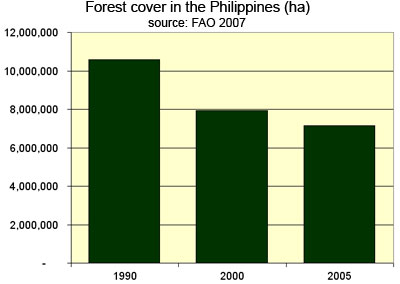

Environmental destruction in the Philippines began centuries ago. The Spanish colonizers harvested timber heavily and expanded European-style agriculture. The 20th century saw mass-scale logging that deforested three-fourths of the island’s forest (the paper’s authors believe that only 6-8% of primary forest remains). In addition, destructive fishing practices, like poisoning and dynamiting, has caused great harm to the rich coral reefs that surround the islands. The wide-spread environmental degradation has caused many endemic species to go extinct and others to become greatly endangered. According to the IUCN 21 percent of the Philippines vertebrates are threatened and over half of the known plant species. But as lead author of the paper, Dr. Mary Posa, told Mongabay.com, “It is easy to characterize the Philippines as a collection of bleak biodiversity statistics that is beyond redemption. What is often disregarded is that there are continuing conservation efforts despite the immense odds.”

The Philippines. Courtesy of Google Earth |

The paper focuses on success stories in endangered species conservation, the protection of threatened ecosystems, the rediscovery of many lost species, and a general change in attitude, leading to many new and vital environmental programs.

The authors present four examples of successful conservation initiatives for endangered species. The Philippine Cockatoo, considered critically endangered, has seen population growth since various programs have worked together incorporating strategies like education, protection of nests, captive breeding, and research. In 1997 a sanctuary was step up to protect a particular population of the species. The critically endangered Visayan Wrinkled Hornbill is another success story: with the help of The Philippine Endemic Species Conservation Project (PESCP) the bird raised 502 successful broods in 2006. The Philippine Crocodile, also considered critically endangered, has benefited from educational programs to change negative perceptions of the animal. Finally, the Philippine Eagle, the national bird and considered one of the world’s most endangered, has recently had good news. Research on the bird’s population has discovered that there may be more eagles than thought and recent conservation methods have increased protection of its threatened habitat.

Critically endangered species are not the only ones benefiting from a widening consciousness of environmentalism in the Philippines. A rise in scientific research on the islands has brought long-lost species back from extinction. The Cebu Flowerpecker, a bird native to Cebu Island had not been sighted since 1906, and was considered extinct until it was rediscovered in a limestone forest in 1992. Not recorded since 1964, three individuals of the Philippine Bare-backed Fruit Bat were netted in 2001, changing its status from extinct to critically endangered. The Philippine Parachute Gecko went unseen for over eighty years before rediscovery in 1993. The Philippine Forest Turtle was also considered extinct until Palawan Island revealed unknown populations. From such a pattern, the paper extracts this lesson: “the uncritical acceptance of a species’ extinction may lead researchers to give up on the species prematurely, and thus the assumption of its demise may become self-fulfilling” and, fortunately “certain endemic species are less extinction-prone than feared”. It also proves the importance of continued field research: currently, such research has found nearly a hundred new species of mammals and herpetofauna, which are only waiting for formal description.

Forest cover in the Philippines |

Fragile ecosystems have also gained increased protection over the past decades, attempting a balance between human-needs and conservation requirements. More than 600 small marine protected areas (MPAs) have been established in the Philippines and are run by local communities. Such areas have shown increases in fish and allow resident fishermen to apply their trade sustainably. Beyond the oceans, parks such as Mount Kitanglad Range Natural Park have provided an excellent example of indigenous tribes managing park systems to the benefit of all. With their management the park has seen a decrease in violations, forest fires, and an increase in tree-planting. Forest rehabilitation has occurred across the Philippines recently: forest area in plantation-form increased 5% in the 1990s.

Conservation and environmentalism has become a hot topic in the Philippines as the populace has experienced first hand the ramification of devastated ecosystems. According to the paper, soil fertility has decreased while pollution has increased due to mining; fisheries have become increasingly less productive while flooding and landslides occur annually due to erosion from deforestation. At the same time the Philippines have seen a rise in scientists, conservationists, and most importantly local programs to protect and rehabilitate the environment. For example, The Wildlife Conservation Society of the Philippines has seen steady growth in membership and new groups are emerging all the time to tackle diverse and local issues: “The Philippine environmental movement gets much of its momentum from committed people who belong to civil society groups. In most cases, these groups are small nonprofit organizations that tackle the multifarious facets of biodiversity conservation.”

The Cloud rat, a species endemic to the Philippines. Photo by Julie Larsen Maher of WCS. |

Despite the signs of progress, the paper stresses that “immense challenges and obstacles remain”. While there are many environmental laws in place, the government needs to do a better job of ensuring enforcement. According to the paper they also need to address with greater urgency issues like pollution, climate change, poverty, and overpopulation. Community-based activism “must provide tangible benefits and be financially stable”. Parks need greater protection on the ground, since many still suffer from illegal logging. As well, to truly protect biodiversity the nation needs more reserves. In light of these positive developments and continuing challenges, global environmental programs should not turn their backs on the Philippines, according to the paper’s authors, but provide greater support for local and long-term programs.

Despite its reputation as environmentally degraded and overpopulated, the Philippines is hardly with hope. Dr. Posa, who is an instructor at the Institute of

Biology at the University of the Philippines stated that she believed the paper would draw more attention “to the positive developments and little-known success stories that we can learn from and build upon. To dismiss the country as a lost cause for conservation would merely create a self-fulfilling prophecy that dooms biodiversity where there are still opportunities for effective action.” The authors of the paper admit that “the Philippine environmental movement was born out of necessity. Greater environmental advocacy and changes in policy have coincided with the near destruction of essential habitats and ecosystems.”

If the vision of the Philippines is based solely on its number of endangered species and its total forest loss, the picture is bleak indeed. But saving species, rebuilding forests, and, in general, regenerating a ravished environment takes a long time, so hope should not be measured solely by statistical negatives, but also by changed minds, on-the-ground success stories, and the devotion of a large number of individuals and organizations who work everyday to bring the Philippines back from the edge of environmental ruin.

Some fascinating additional statistics from the paper “Hope for Threatened Tropical Biodiversity: Lessons from the Philippines”:

- Only 5 percent of the Philippines coral reefs retain 75-100 percent of live coral cover.

- Forest rate is still on the decline by 1.9 percent annually.

- Of 1100 terrestrial vertebrates known in the Philippines almost half are endemic.

- 45-60 percent of vascular plants are endemic.

- In 1988, 43 species of birds were considered threatened; in 1994, 86 species were listed; in 2006, 69 species were listed as threatened or worse.

- In 2006 a survey of 156 marine protected areas in the Philippines showed that almost half were under good to excellent management.

- In 1993 approximately 70 individuals attended the annual symposium of the Wildlife Conservation Society of the Philippines, approximately 170 attended in 2006.

- Publications on biodiversity and conservation in the Philippines have more than doubled in two decades.

- In 1998, 13 critically endangered Philippine crocodiles were reported killed in San Mariano, only 3 were reported killed in 2003.

- In 1998-1999 just over 20 Philippine cockatoos were observed, in 2005 approximately a hundred were observed.

Photo take Feb 4, 2008 by Julie Larsen Maher / WCS. |

Mary Rose C. Posa, Arvin C. Diemos, Navjot S. Sodhi, and Thomas M. Brooks (2008). Hope for Threatened Tropical Biodiversity: Lessons from the Philippines. Vol. 58 No. 3, BioScience.