China’s emissions growth 2-4 times greater than expected

China’s emissions growth 2-4 times greater than expected

mongabay.com

March 10, 2008

|

|

China’s carbon dioxide emissions are growing far faster than anticipated according to according to a new analysis by economists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of California, San Diego.

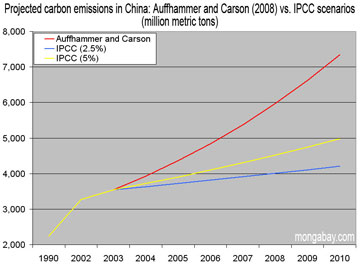

The study, published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, estimates China will see an 11 percent annual growth rate in CO2 emissions between 2004 and 2010, two to four times the 2.5 to 5 percent growth rate estimated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Under their most conservative forecast, Maximillian Auffhammer (UC Berkeley) and Richard Carson (UC San Diego) predict that by 2010 China will see an increase of 600 million metric tons of carbon emissions over the its 2000 levels.

“This growth from China alone would dramatically overshadow the 116 million metric tons of carbon emissions reductions pledged by all the developed countries in the Kyoto Protocol,” stated a release from UC San Diego. “Put another way, the projected annual increase in China alone over the next several years is greater than the current emissions produced by either Great Britain or Germany.”

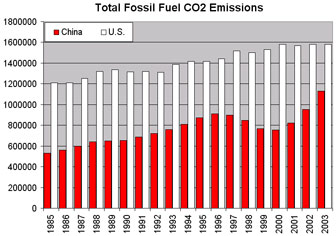

Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels for the U.S. and China, 1985-2003. Data from EIA. |

The researchers say the increase will challenge efforts to stabilize greenhouse gas emissions.

“It had been expected that the efficiency of China’s power generation would continue to improve as per capita income increased, slowing down the rate of CO2 emissions growth. What we’re finding instead is that the emissions growth rate is surpassing our worst expectations, and that means the goal of stabilizing atmospheric CO2 is going to be much, much harder to achieve,” said Auffhammer.

Why IPCC estimates were so far off the mark

Whereas other studies have used nationwide information about energy use in China dating from a decade ago, Auffhammer and Carson used emissions data from China’s 30 provincial entities.

“Everybody had been treating China as single country, but each of the country’s provinces is larger than many European countries, both in geographic size and population,” said Carson. “In addition, there is a wide range in economic development and wealth from one province to the next, as well as major differences in population growth, all of which has an effect on energy consumption that cannot be easily addressed in models based upon aggregate national data.”

“A notable shift occurred in China around the year 2000, around the time when hope for an agreement with the U.S. on the Kyoto Protocol began to diminish along with external pressure for China to reduce its emissions,” said Carson. “Energy use started to grow faster than income, and much of the energy that was used wasn’t efficient.”

|

The authors say that decentralization accelerated increase emissions by “shifting the responsibility for building new power plants to provincial officials who had less incentive and fewer resources to build cleaner, more efficient plants, which save money in the long run but are more expensive to construct.”

“Government officials turned away from energy efficiency as an objective to expanding power generation as quickly as they can, and as cheaply as they can,” said Carson. “Wealthier coastal provinces tended to build clean-burning power plants based upon the very best technology available, but many of the poorer interior provinces replicated inefficient 1950s Soviet technology.”

“The problem is that power plants, once built, are meant to last for 40 to 75 years,” said Carson. “These provincial officials have locked themselves into a long-run emissions trajectory that is much higher than people had anticipated. Our forecast incorporates the fact that much of China is now stuck with power plants that are dirty and inefficient.”