Cheap cattle loans may be driving surge in Amazon deforestation

Cheap ranch loans may be driving jump in Amazon deforestation

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

February 12, 2008

|

|

Surging deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon may be partly the result of new financial incentives given by state banks such as the Bank of Amazon (BASA), reports Agência de Noticias da Amazônia, a Brazilian newspaper, and the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO).

According to Agência de Noticias da Amazônia, small to large-size cattle ranchers in the state of Pará have received payments to expand cattle production in the state, which has resulted in deforestation. While federal law requires ranches to retain 80 percent of the forests on their land, BASA reportedly exempts loan applicants from providing proof of these legal forest reserves. Further, “BASA offers subsidized interest rates for cattle ranching activities ranging from 0.5% to 10.5%” — rates considered some of the lowest in the country, according to the ITTO.

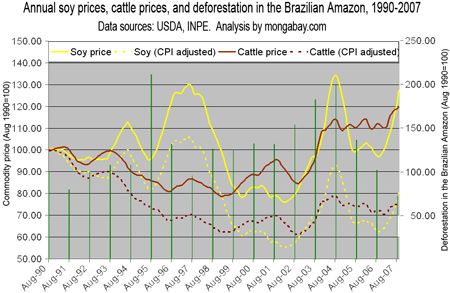

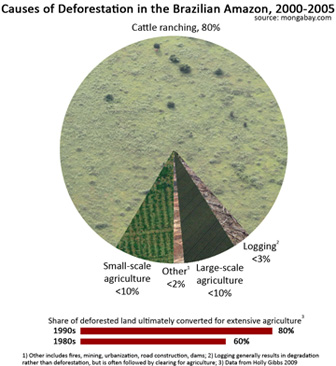

By some estimates, roughly two-thirds of historic rainforest destruction in the Brazilian Amazon results from clearing for cattle pasture, much of which was traditionally driven by land speculators seeking to benefit from appreciating real estate values. While land prices continues to rise, today the beef business is booming in the Amazon — 96 percent of Brazil’s cattle herd growth between December 2003 and December 2006 occurred in the legal Amazon. Additional impetus comes from high soy prices which are driving conversion of some pasture land for industrial soy farms, necessitating the need to clear more forest.

The recent surge in soy and cattle prices could be driving an increase in forest fires. Annual deforestation figures for the 2007-2008 year will not be released until August of 2008. |

In late 2007 with grain and cattle prices near record levels, Brazilian satellites detected a marked increase in the number of fires and deforestation in the states of Para and Mato Grosso — the heart of Brazil’s booming agricultural frontier. Both experienced a 50 percent or more increase in forest loss over the same period last year coupled with a large jump in burning: a 39-85 percent jump in the number of fires in Para during the July-September burning period and 100-127 percent rise in Mato Grosso, depending on the satellite. More broadly, the 50,729 fires recorded by the Terra satellite and 72,329 measured by the AQUA satellite across the Brazilian Amazon are the highest on record based on available data going back to 2003. In January 2008 the Brazilian government announced that deforestation for the 2007-2008 year world likely double over the previous period.

In response, Brazilian authorities announced a plan to crack down on illegal clearing for agriculture, including sending thousands of police into the region. Still with recent forest conversion increasingly linked with beef and soy prices, it seems likely that the law enforcement effort will face significant challenges.

Some believe industry-led efforts to improve sustainability of the beef industry may be the best hope for reining in Amazon forest loss. In March the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private equity lender of the World Bank, announced a $90 million loan to the Bertin Group for an “ecological” meat-packing facility in Marabá in Para. While some environmentalists criticized the deal, a leading expert on the Amazon said that it could play a key part in improving environmental compliance in the region.

Chart created by Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com. |

“There comes a point where we have to acknowledge that the region is undergoing an economic transformation and if we can find a powerful lever for commodifying how this transformation takes place — putting a premium on legal land-use practices, legal deforestation, the gradual elimination of the use of fire — we should take it. For me that trumps the negative consequences of setting up increased capacity in the region,” Dr. Daniel Nepstad, a scientist at the Woods Hole Research Institute, told mongabay.com.

In other words, I really do believe that there are many responsible cattle ranchers and soy farmers in the Amazon who are waiting for some sort of recognition through positive incentives. The incentive could be a very small mark up — literally a few cents per pound of beef sold — but it would send a signal to these ranchers that if they want to participate in the new beef economy, they better have their legal forest reserve in order or have compensated for it, maintain or be in the process of restoring their riparian zone forests, control erosion, and get their cows out of the streams and into artificial watering tanks. There is a whole range of positive things that can happen once cattle ranchers see that if they do things right they are rewarded. This means that as Brazil moves forward as the world’s leading exporter of beef — with tremendous potential to expand — we have a way to shape that expansion as it takes place to reduce the negative ecological impacts.”

Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon rainforest?

John Cain Carter believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter is a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago with his Brazilian wife, Kika, and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Aliança da Terra. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. While deforestation rates in the Amazon have accelerated, the problem is not a lack of laws, but rather a legal system where enforcement is so slow and so corrupt that it renders the laws effectively useless. On paper, cattle ranching in the Amazon may be the most restricted in the world, with landowners required to keep 80 percent of their land forested — a limitation no rancher in Texas faces. Carter wants to see farmers in Brazil benefit in following the law, by turning this restriction into a marketing advantage. However in order to do so, Amazon producers have to ensure that consumers ( i.e., buyers of commodities like McDonalds, Wal-Mart, and Cargill) can confidently say that agricultural products are produced legally and even more sustainably than stipulated by the law. The incentive for producers is market access: Aliança da Terra helps Brazilian farmers and ranchers get the best price for their products, but only if they follow the rules. While producers get higher prices for their goods, buyers like Burger King and Archer-Daniels Midland can say they are using legally and responsibly produced beef. Meanwhile more rainforest is left standing, ecosystem services preserved, and biodiversity conserved. Everybody wins.