Biofuels are worsening global warming

Biofuels are worsening global warming

Rhett Butler, mongabay.com

February 7, 2008

|

|

Converting native ecosystems for production of biofuel feed stocks is worsening the greenhouse gas emissions they are intended to mitigate, reports a pair of studies published in the journal Science. The studies follow a series of reports that have linked ethanol and biodiesel production to increased carbon dioxide emissions, destruction of biodiverse forest and savanna habitats, and air and water pollution.

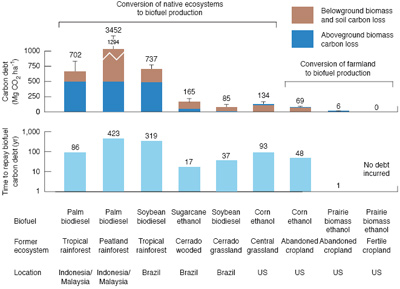

Analyzing the lifecycle emissions from biofuels, the first study found that carbon released by converting rainforests, peatlands, savannas, or grasslands often far outweighs the carbon savings from biofuels. Conversion of peatland rainforests for oil palm plantations for example, incurs a “carbon debt” of 423 years in Indonesia and Malaysia, while the carbon emission from clearing Amazon rainforest for soybeans takes 319 years of renewable soy biodiesel before the land can begin to lower greenhouse gas levels and mitigate global warming.

Chart modified from Science |

“This research examines the conversion of land for biofuels and asks the question ‘Is it worth it”‘,” said lead author Joe Fargione, a scientist for The Nature Conservancy. “The answer is no.”

“These natural areas store a lot of carbon, so converting them to croplands results in tons of carbon emitted into the atmosphere.” Fargione continued, “We analyzed all the benefits of using biofuels as alternatives to oil, but we found that the benefits fall far short of the carbon losses. It’s what we call ‘the carbon debt.’ If you’re trying to mitigate global warming, it simply does not make sense to convert land for biofuels production. All the biofuels we use now cause habitat destruction, either directly or indirectly. Global agriculture is already producing food for six billion people. Producing food-based biofuel, too, will require that still more land be converted to agriculture.”

U.S. ethanol worsens global warming

While a number of studies have shown that conversion of tropical ecosystems, including peat swamps in Southeast Asia and rainforests and grasslands in South America, for energy crops result in net emissions, the second study shows that when assessed at a global level, U.S. corn ethanol is also a major CO2 source — not a CO2 sink as usually claimed by the farm industry.

“Using a worldwide agricultural model to estimate emissions from land use change, we found that corn-based ethanol, instead of producing a 20% savings, nearly doubles greenhouse emissions over 30 years and increases greenhouse gasses for 167 years,” write the authors.

Their assessment is based on the additional land that needs to be converted abroad as a result of increased corn acreage planted for ethanol production in the United States.

Dying oil palms in Costa Rica |

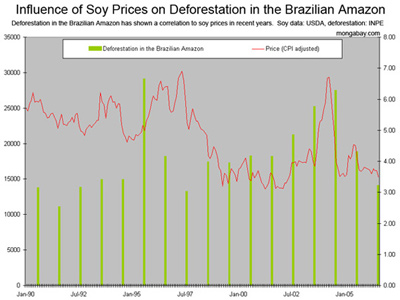

“To produce biofuels, farmers can directly plow up more forest or grassland, which releases to the atmosphere much of the carbon previously stored in plants and soils through decomposition or fire,” write the authors. “The loss of maturing forests and grasslands also forgoes ongoing carbon sequestration as plants grow each year, and this foregone sequestration is the equivalent of additional emissions. Alternatively, farmers can divert existing crops or croplands into biofuels, which causes similar emissions indirectly. The diversion triggers higher crop prices, and farmers around the world respond by clearing more forest and grassland to replace crops for feed and food. Studies have confirmed that higher soybean prices accelerate clearing of Brazilian rainforest.”

In particular, the authors — including researchers from Princeton University, Agricultural Conservation Economics, the Woods Hole Research Center, and Iowa State University — say that U.S. corn ethanol production is having a global effect. As U.S. corn exports declined sharply, production picks up in other countries where yields are lower, requiring conversion of more land for production, and driving global grain prices even higher.

Misplaced incentives

The researchers say the current system has misplaced incentives: farmers are rewarded for the amount of biofuel produced while the resulting carbon emissions are ignored.

“We don’t have proper incentives in place because landowners are rewarded for producing palm oil and other products but not rewarded for carbon management,” said University of Minnesota Applied Economics professor Stephen Polasky, a co-author of the study. “This creates incentives for excessive land clearing and can result in large increases in carbon emissions. Creating some sort of incentive for carbon sequestration, or penalty for carbon emissions, from land use is vital if we are serious about addressing this problem.”

Influence of soybean prices (CPI-adjusted) on deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. All figures in hectares (2.47 acres). |

Still the authors say that some biofuels do not contribute carbon emissions to the atmosphere because they do not require clearing of native vegetation. These include fuels produced from agricultural waste, weedy grasses, and woody biomass grown on lands unsuitable for conventional crops.

“Biofuels made on perennial crops grown on degraded land that is no longer useful for growing food crops may actually help us fight global warming,” said University of Minnesota researcher Jason Hill, a co-author. “One example is ethanol made from diverse mixtures of native prairie plants. Minnesota is well poised in this respect.”

The researches recommend that the full environmental impact of biofuel production be evaluated when making decisions on energy sources.

“In finding solutions to climate change, we must ensure that the cure is not worse than the disease,” noted Jimmie Powell, who leads the energy team at The Nature Conservancy. “We cannot afford to ignore the consequences of converting land for biofuels. Doing so means we might unintentionally promote fuel alternatives that are worse than fossil fuels they are designed to replace. These findings should be incorporated into carbon emissions policy going forward.”

“We will need to implement many approaches simultaneously to solve climate change. There is no silver bullet, but there are many silver BBs,” said Fargione. “Some biofuels may be one silver BB, but only if produced without requiring additional land to be converted from native habitats to agriculture.”

References

- Fargione, J. el al (2008). Land Clearing and the Biofuel Carbon Debt. Science, Feb 8, 2008.

- Searchinger, T. el al (2008). Use of U.S. Croplands For Biofuels Increases Greenhouse Gasses Through Emissions From Land Use Change. Science, Feb 8, 2008.

Earlier articles

Amazon deforestation jumps in the second half of 2007

(1/24/2008)

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon rose sharply in the second half of 2007 as a result of surging prices for beef and grain, said a top Brazilian environmental official.

|

|

Amazon deforestation surging due to oil, soy prices

(1/17/2008)

A Brazilian scientist has confirmed that forest clearing in the Amazon rainforest has surged in recent months, according to Reuters.

U.S. biofuels policy drives deforestation in Indonesia, the Amazon

(1/17/2008)

U.S. incentives for biofuel production are promoting deforestation in southeast Asia and the Amazon by driving up crop prices and displacing energy feedstock production, say researchers.

Switchgrass a better biofuel source than corn

(1/7/2008) Switchgrass yields more than 540 percent more energy than the energy needed to produce and convert it to ethanol, making the grassy weed a far superior source for biofuels than corn ethanol, reports a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Leading biofuels wreak environmental havoc

(1/3/2008) Biofuels made from world’s dominant energy crops — including corn, soy, and oil palm — may have worse environment impacts than conventional fossil fuels, reports a study published in the journal Science.

Palm oil is a net source of CO2 emissions when produced on peatlands

(12/17/2007) Researchers have confirmed that converting peat forests for oil palm plantations results in a large net release of carbon dioxide, indicating industry claims that palm oil helps fight climate change are unfounded, at least when plantations are established in peatlands.

U.S. corn subsidies drive Amazon destruction

(12/13/2007) U.S. corn subsidies for ethanol production are contributing to deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, reports a tropical forest scientist writing in this week’s issue of the journal Science.

Kyoto pact ignores CO2 emissions from biofuels

(12/5/2007) The Kyoto climate pact, as it currently stands, ignores millions of tons of carbon dioxide emissions from the drainage of peatsoils for palm oil production in Indonesia and Malaysia, warnned Wetlands International, an international NGO, in a report released at the UN climate meeting in Bali.

Tropical forests face huge threat from industrial agriculture

(12/5/2007) With forest conversion for large-scale agriculture rapidly emerging as a leading driver of tropical deforestation, a new report from the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) suggests the trend is likely to continue with Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Peru, and Colombia containing 75 percent of the world’s forested land that is highly suitable for industrial agriculture expansion. Nevertheless the study identifies forests that may be best suited (low population density, unsuitable climate and soils) for “Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation” (REDD) initiatives which compensate countries for preserving forest lands in exchange for carbon credits.

Cooking oil, palm oil biodiesel can reduce emissions relative to diesel

(11/28/2007) A lifecycle analysis of biodiesel by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) shows that using palm oil derived from existing plantations can be an effective biofuel feedstock for reducing greenhouse gas emissions relative to conventional diesel fuel. However, palm oil sourced from rainforest and peatlands generating emissions 8 to 21 times greater than those from diesel.

Is the oil-palm industry using global warming to mislead the public?

(11/23/2007) Members of the Indonesian Palm Oil Commission are distributing materials that misrepresent the carbon balance of oil-palm plantations, according to accounts from people who have seen presentations by commission members. These officials are apparently arguing that oil-palm plantations store and sequester many times the amount of CO2 as natural forests, and therefore that converting forests for plantations is the best way to fight climate change. In making such claims, these Indonesian representatives evidently are ignoring data that show the opposite, putting the credibility of the oil-palm industry at risk, and undermining efforts to slow deforestation and rein in greenhouse gas emissions.