U.S. corn subsidies drive Amazon destruction

U.S. corn subsidies drive Amazon destruction

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

December 13, 2007

|

|

U.S. corn subsidies for ethanol production are contributing to deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, reports a tropical forest scientist writing in this week’s issue of the journal Science.

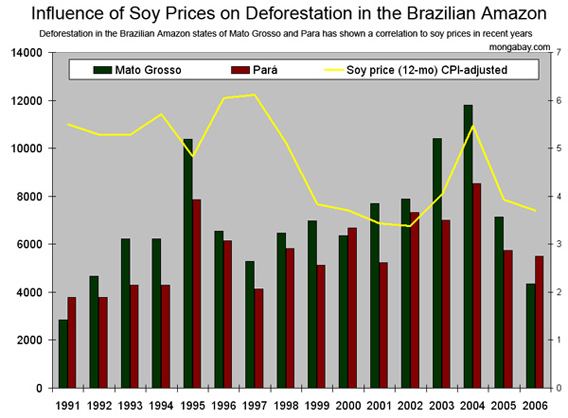

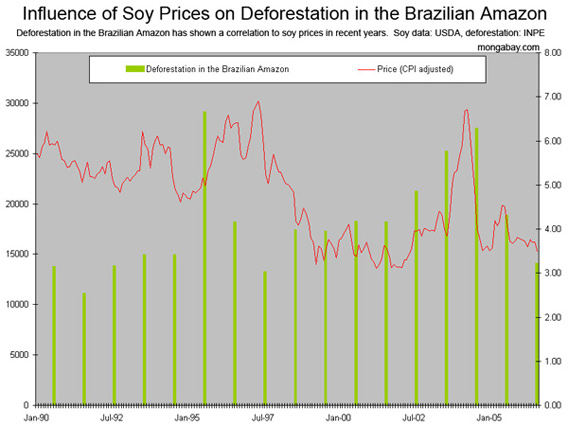

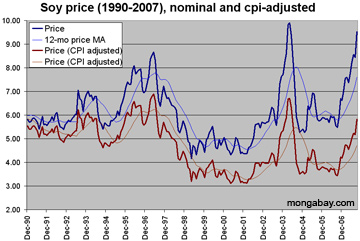

Dr. William Laurance, of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, says that a recent spike in Amazonian forest fires may be linked to U.S. subsidies that promote American corn production for ethanol over soy production. The shift from soy to corn has led to a near doubling in soy prices during the past 14 months. High prices are, in turn, driving conversion of rainforest and savanna in Brazil for soy expansion.

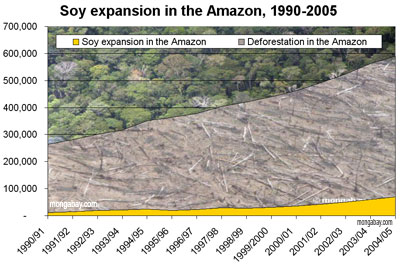

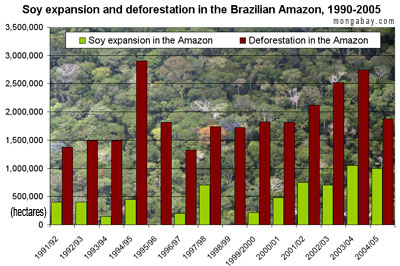

Annual deforestation rates and annual soy expansion for states in the Brazilian Amazon 1990-2005. Note that the 1995-1996 and 1998-1999 years were negative and do not show up on the chart. Graphs based on Brazilian government data.

|

“American taxpayers are spending $11 billion a year to subsidize corn producers—and this is having some surprising global consequences,” said Laurance. “Amazon fires and forest destruction have spiked over the last several months, especially in the main soy-producing states in Brazil. Just about everyone there attributes this to rising soy and beef prices.”

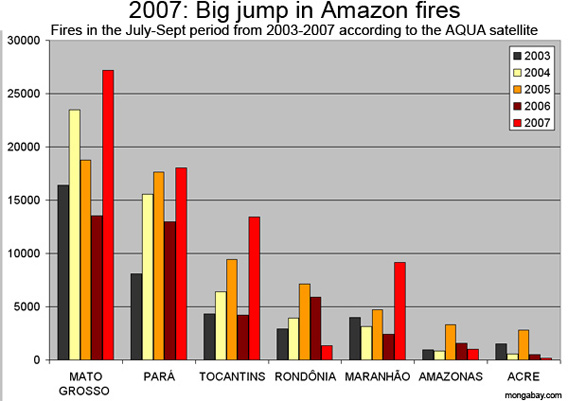

Brazilian satellite data show a marked increase in the number of fires and deforestation in the region. The states of Para and Mato Grosso — the heart of Brazil’s booming agricultural frontier — both experienced a 50 percent or more increase in forest loss over the same period last year coupled with a large jump in burning: a 39-85 percent jump in the number of fires in Para during the July-September burning period and 100-127 percent rise in Mato Grosso, depending on the satellite. More broadly, the 50,729 fires recorded by the Terra satellite and 72,329 measured by the AQUA satellite across the Brazilian Amazon are the highest on record based on available data going back to 2003 (the NMODIS-01D satellite suggests 2005 burning was higher but still shows a 54 percent jump since last year). Reports from the ground indicate that burning is indeed very bad this year.

|

“I have never seen fires this bad,” John Cain Carter, a rancher who runs the NGO Aliança da Terra, told mongabay.com. “The fires are even worse than in 1998´s El Niño event… A huge area of the Xingu National Park was on fire, truly sickening as it is a sign of things to come.”

Laurance says that high soy prices affect the Amazon both directly and indirectly.

“Some forests are directly cleared for soy farms. Farmers also purchase large expanses of cattle pasture for soy production, effectively pushing the ranchers further into the Amazonian frontier or onto lands unsuitable for soy production,” Laurance explained.

Soybean cultivation in the Brazilian Amazon has expanded at a rate of 14.1 percent per year since 1990—16.8 percent annually since 2000—and now covers more than eight million hectares.

“In addition,” continued Laurance, “higher soy costs tend to raise beef prices because soy-based livestock feeds become more expensive, creating an indirect incentive for forest conversion to pasture. Finally, the powerful Brazilian soy lobby has been a driving force behind initiatives to expand Amazonian highway networks, which greatly increase access to forests for ranchers, farmers, loggers, and land speculators.”

Satellite imagery from NASA supports Laurance. Data released this summer indicates that much of the recent burning is concentrated around two major Amazon roads: Trans-Amazon highway in the state of Amazonas, and the unpaved portion of the BR-163 Highway in the state of Pará.

Laurance says that while it is too early to conclusively show the impact of U.S. corn subsidies, “we’re seeing that these predictions—first made last summer by the Woods Hole Research Center’s Daniel Nepstad and colleagues—are being borne out. The evidence of a corn connection to the Amazon is circumstantial, but it’s about as close as you ever get to a smoking gun.”

“Biofuel from corn doesn’t seem very beneficial when you consider its full environmental costs,” said Laurance. “Corn-based ethanol is supposed to reduce greenhouse gases, but it’s unlikely to do so if it promotes tropical deforestation—one the main drivers of harmful climate change.”

The U.S. corn harvest will be 335 million tons this year, up 25 percent since last year. About 85 million tons of this will be converted into ethanol, up from 15 million tons in 2000. The World bank estimates that the amount of corn needed to fill the gas tank of an SUV is enough to feed a person for a year.