70% of rainforest island to be cleared for palm oil

70% of rainforest island to be cleared for palm oil

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

December 13, 2007

Setback for Islanders Opposing Deforestation on Woodlark Island for Biofuels

|

|

Mongabay.com received information this week that the Malaysian company Vitroplant has been granted the permit it needs to begin developing 70% of Woodlark Island into palm oil plantations. In an e-mail received by one of the opposition leaders to Vitroplant, Dr. Simon Piyuwes said that “the government granted the permit to the oil palm company despite a widespread campaign and pressure from NGOs”. In an earlier article Dr. Piyuwes stated that “we [the islanders] do not have money to fight the giant. We only hope for the support from the NGOs, and the mercy of the government to withdraw the project.” It seems the government has refused Dr. Piyuwes what he hoped for.

Late December 2006. A young man, part of a large group of people from Wabunun village in southeastern Muyuw, kneeding thrashed sago to separate out the starch for later eating. The sago orchard from which this picture is taken is in the southcentral part of the island adjacent to the mountaineous and igneous core of the island often generically called Sulog. Although sparsely populated now, this region is a massive resource base and part of the island’s place in the much larger regional system that covers much of Milne Bay Province. Sago is a food used for the trough of the agricultural year (anytime from November to March), as a ritual delicacy at any time, but most often during the mortuary season (…June-August…), as an exchange item for resources from other islands, and, importantly, as a fallback for crises regularly but unpredictably occurring with el nino events (“Big suns”). |

The situation is complex. Woodlark Island is a small island in the Pacific under the government of Papua New Guinea. The island is 80,000 hectares, consisting mostly of forest and coastline. The population is small—6,000 residents in all—who live by gardening and hunting. Vitroplant’s plan to convert 60,000 acres to palm oil plantations for biofuels would deforest the majority of the island, putting numerous species at risk of extinction and drastically changing the lifestyles of the populace. Dr. Piyuwes admits that there may be economic and infrastructure benefits from the Vitroplant plan, but he says the disadvantages far outweigh the advantages. Scientists agree.

Woodlark Island is home to a large number of endemic species, including the Woodlark Cuscus, a speckled nocturnal marsupial. A total of nineteen other endemic species have been identified on the small island alone, from a gecko to a damselfly. Yet this is probably not the end of Woodlark Island’s endemic species; Dr. Chris Norris, a zoologist and paleontologist who has studied the Woodlark Cuscus, states that “because of its relative remoteness, Woodlark Island’s fauna and flora has been very poorly surveyed … I would say that there is a strong probability of more endemic plants and animals that have still to be described.” If 70% of the island is deforested it could lead to the endangerment and even extinction of certain species, including the Woodlark Cuscus.

Early January 2007:The famous Kula elder of Wabunun village, Dibolel, with his wife from Mwadau village on the far western end of the island and their granddaughter sitting behind Dibolel’s three baskets of veigun, shell necklaces. These are one of the two valuables that circulate clockwise around the circle of islands for which Muyuw (Woodlark) is the northeastern corner. Four mwal, armshells, that Dibolel in fact made, are hanging behind him. These are wealthy and very productive people. |

Aside from endangerment of rare and endemic species, there are other environmental considerations. Dr. Dan Polhemus has found that the “implementation of plantation monocultures [like palm oil] invariably degrades freshwater ecosystems, particularly streams. Stream channels are straightened for better drainage, thereby reducing habitat complexity… Forest clearing creates treefalls which block streams…. Riparian canopy cover is lost, thereby increasing sunlight and increasing water temperatures…. Fertilizers and other agrochemicals run off into the streams, creating a proliferation of benthic algae.” Dr. Dan Polhemus has seen this degradation of water resources before in New Britain, the Sagarai River basin, Malaysia, and Vietnam. He adds that, “Overall, the conversion from lowland forest to plantation is a significant and destructive ecosystem transformation.” Dr. F.H. Damon, an anthropologist who has been studying the island’s culture for over thirty years, poses the question “when the owners [of the company] discover that the basic soils of the island are quite extraordinarily impoverished and they start dumping fertilizers and pesticides on the place, what happens to the surrounding reef systems?”

1996 Color aerial shot of se.sector of the island. You can see the intentional mottled pattern, the interpaterning of high forests and gardens that is designed to, among other things, produce environments good for people, their crops, and the cuscus. |

While obviously concerned about environmental damage, Dr. Damon is even more worried about how the palm plantations will affect the unique island culture. He describes the island as one in which humans and animals have lived together in synthesis for millennia. The Woodlark Islanders live off subsistence gardening, herding wild pigs, and occasional hunting. Dr. Damon states that while the islanders are also dependent on rice from abroad, “there remains on the island something of a unique example of a regional social and ecological system that supported human and other life for 2000 and more years.” While the island appears wild, few places have been untouched by humans: “areas regularly cut for gardens—fields—were systematically marked by much higher stands of forest that were to be left uncut. There the [Woodlark Cuscus] slept during the day; and there they would be sought the few months of the year when they were valued for their meat and fat; pigs and fish, of course, were vastly preferred… People regularly burned small plots of that larger area to maintain small meadows. These meadows were places for wild pigs to hang out during droughts or floods, tend their young, and hide from humans when the latter sought them for food… Both the high forests and these meadows are associated with sago orchards, which also seem wild, but which are also part of a management strategy effected on this island.

The sago was also cut and harvested so that roughly two meters of each tree cut would be left as food for the ‘wild’ pigs.” These management practices of the island’s resources, which may seem unconventional, have left a healthy population of cuscus, wild pigs, humans, and the forests that contain so much other bio-diversity.

July, 2002. Bungalau, one of the meadows in the southcentral part of the island regularly burned during el nino droughts. In addition to some valuable boat and body adornment products, it provides a safe haven for “wild pigs.” The tree in the center of the picture is a sago tree, said to be the Creator’s Sago. It is never cut, but grows, flowers, dies, and grows again. This meadow is surrounded by sago orchards which are harvested when needed. |

The island is apart of the Kula system, meaning the islanders have learned to survive in an area of intense weather shifts. Dr. Damon states that the factors the islanders used to survive, i.e. “specific garden/fallow system and the high forest/meadow/sago system” is an adaptation “to El Nino droughts, and I suppose La Nina floods, that regularly, but unpredictably, inflict this area.” The islanders stand as a testament of human ingenuity and an incredible example of the sustainable management of resources. If Vitroplant goes ahead with it plans, Dr. Damon concludes that “all this stuff will be destroyed. In its rough and ready way it was a sustaining, if forever transforming, system in a region not kind to human habitation.”

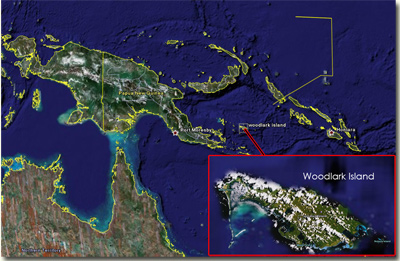

Map modified from Google Earth |

Other opinions have emerged over the past weeks. The National, a daily newspaper in Papua New Guinea, reported in an article on November 18th that many of the islanders actually want Vitroplant’s plantations. In the article William Bernard, president of the Milne Bay PMV Association, is quoted as saying that “certain greedy, selfish, self-centered people who think only of themselves were preventing such development”. He also claimed the people opposing the project had “no links to the island”. Dr. Piyuwes, one of the opposition’s leaders, was born and raised on Woodlark Island; although he now lives elsewhere, he states that he returns to Woodlark “every holiday.” In a previous article Dr. Piyuwes also stated that “every individual Woodlark Islander opposes the project”, contradicting Mr. Bernard’s assertion. Unfortunately attempts to contact Mr. Bernard for a statement proved unsuccessful. As well—for a second time—Vitroplant Ltd.’s representative Dr. Marek Lumbomski did not respond to queries. Dr. Lumbomski is also the executive chairman of Overseas and General Limited, an Australian company that deals in hard wood tree plantations.

Could the Woodlark Cuscus go the way of the dodo? Photo by Tim Flannery |

While biofuels are being grown across Asia—deforesting countless hectares—it has been shown in several studies that palm oil plantations grown on what was once tropical forest release 8 to 21 times more carbon than diesel. So, in this case, biofuels actually cause more global warming than SUVs. In the case of Woodlark Island such plantations may also cause widespread endangerment of the island’s flora and fauna, environmental upheaval, and drastic cultural change. Dr. Simon Piyuwes states that the islanders will continue their opposition: “the people of Woodlark will take on every means to stop this.” But without more aid (and awareness) from the international community that task may prove long and extremely difficult.

Now that the government has granted Vitroplant the license to develop Woodlark Island—pushing the island one step closer to deforestation—perhaps it’s not too much to say that the biofuel plantations will turn a bio-diverse paradise into a monoculture, and bring environmental disaster down upon a unique culture.

Previous

Biofuels versus Native Rights

On Woodlark Island, one-hundred and seventy miles from Papua New Guinea, a struggle is occurring between islanders and biofuel company Vitroplant Ltd. The company is planning to clear much of the island’s forest for oil palm plantations to produce biofuels. Vitorplant Ltd.’s contract specifies that they would deforest 60,000 hectares of land for plantations; Woodlark Island is 85,000 hectares in total, meaning over 70% of the island would be converted. Last week, one hundred islanders (out of a total population of 6,000) traveled to the capital of Milne Bay Province, Alotau, to voice their concern over the plans to turn their forested island into plantations.