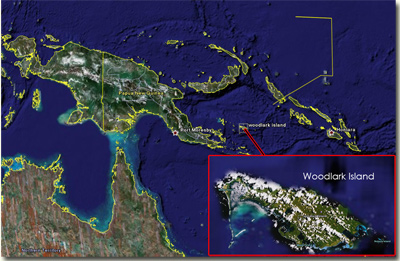

- On Woodlark Island, one-hundred and seventy miles from Papua New Guinea, a struggle is occurring between islanders and biofuel company Vitroplant Ltd.

- The company is planning to clear much of the island’s forest for oil palm plantations to produce biofuels.

- Vitorplant Ltd.’s contract specifies that they would deforest 60,000 hectares of land for plantations; Woodlark Island is 85,000 hectares in total, meaning over 70% of the island would be converted.

- Last week, one hundred islanders (out of a total population of 6,000) traveled to the capital of Milne Bay Province, Alotau, to voice their concern over the plans to turn their forested island into plantations.

On Woodlark Island, one-hundred and seventy miles from Papua New Guinea, a struggle is occurring between islanders and biofuel company Vitroplant Ltd. The company is planning to clear much of the island’s forest for oil palm plantations to produce biofuels. Vitorplant Ltd.’s contract specifies that they would deforest 60,000 hectares of land for plantations; Woodlark Island is 85,000 hectares in total, meaning over 70% of the island would be converted. Last week, one hundred islanders (out of a total population of 6,000) traveled to the capital of Milne Bay Province, Alotau, to voice their concern over the plans to turn their forested island into plantations.

Leading the opposition is medical doctor Simon Piyuwes. Dr. Piyuwes was born and raised on the island and returns every holiday. On his most recent homecoming, Dr. Piyuwes found himself taking on a new role. He says that “every individual Woodlark Islander opposes the project. However it appears that the LLG president who was supposed to represent the people was pushing for the project. Compelled by this I felt the responsibility to talk for my people.” Dr. Piyuwes outlines several reasons why Vitroplant Ltd.’s plans are unacceptable to the islanders. He states that the logging would destroy the island’s endemic ebony, cause extinctions of rare species, and threaten marine life by waste from the project. Not only does he foresee environmental disaster, but also disintegration of the native culture, stating that the company’s plans would bring “socially unacceptable behavior on the island”. And that all the islanders would eventually be threatened with “starvation” since “there will be no space for gardening and hunting”. Dr. Piyuwes admits that while there may be some economic and infrastructure benefits to the island, he believes the disadvantages far outweigh the advantages.

Map modified from Google Earth |

According to the islanders, they were never consulted regarding the plans until after the government had already granted the lease to Vitroplant Ltd. “We were shocked to hear the announcement that the oil palm project is set to begin in few months time,” Dr. Piyuwes states, adding that “we were simply told that the land belongs to the government and we have no right to talk.” But the people of Woodlark argue that the land is theirs by right. It was initially taken away in the 1880s by colonial powers, during this period Dr. Piyuwes stresses that the population was illiterate and communication regarding the ownership of the land “doubtful”. To bolster the case that the island belongs to its inhabitants, the Woodlark islanders point to several former ministers that promised to return of the land to the islanders. Woodlark Islanders currently live by gardening of such crops as yams, taro, sweet potatoes, and bananas. Fishing and hunting play a smaller, though important, role in their diet.

Chris Norris, a zoologist and paleontologist who visited Woodlark Island in 1987, describes it as low-lying, aside from a chain of hills in the middle. He states that “apart from some of the coastal areas, most of the island is covered in dense lowland rain forest.” Dr. Piwuyes adds that his homeland is “a beautiful island with virgin forest”.

A Gold Mine of Endemic Species

It is not just Woodlark Island’s natives who are worried over Vitroplant Ltd’s plan. Numerous scientists and conservationists share their concern. Woodlark Island is home to a number of species found nowhere else in the world. A transformation from forest to plantations would cause several species, now abundant, to become threatened. In the worse case scenario, the lack of habitat could create widespread extinction.

Could the Woodlark Cuscus go the way of the dodo? Photo by Tim Flannery |

The most well-known endemic animal to Woodlark Island is the Woodlark Cuscus. Cuscus are medium-sized nocturnal marsupials. Dr. Kristopher Helgen, a mammalogist who focuses on species in the Papua New Guinea and its islands, describes the species as “the most visible and charismatic of the endemic animals of Woodlark. It is a very distinctive species and is reliant on forests.” Long thought to be rare, the species’ population was studied in 1987 by Dr. Norris. Dr. Norris found that the Woodlark Cuscus was more abundant than had been believed. The people of the island do not threaten the Cuscus through their small-scale gardening and hunting, and the species is currently listed as Least Concern by the IUCN, but Dr. Norris states “any significant clearance of forest, such as would be required for the Vitroplant proposal, would pose a grave risk of extinction.”

The Woodlark Cuscus is not the only species endemic to the island; in fact the island, which was never connected to the mainland of Papua New Guniea, contains a vast number of endemic species, including a rodent, which has not yet received a scientific name; a gecko, Cyrtodactylus murua, which was only described by science in 2006; a second lizard species; two species of frog; and fourteen endemic mollusks. Additionally, four endemic insect species live on Woodlark—two damselflies, a water bug, and a riffle bug. Two of these insects are confined solely to forest habitat. Dr. Polhemus, an entomologist who surveyed the island in 2003, discovering two insect species, states that “it is all but certain that there are other endemic species in the material” gathered during his survey. Despite the many endemic species already described on Woodlark Island, Dr. Norris concurs with Polhemus, “because of its relative remoteness, Woodlark Island’s fauna and flora has been very poorly surveyed […] I would say that there is a strong probability of more endemic plants and animals that have still to be described.”

Under current plans—to deforest over 70% of the island—it is impossible to imagine how these species could be sufficiently protected. When asked to consider the issue, Dr. Norris had this to say, “obviously there are various factors that have to be weighed up when calculating the benefits of a scheme like this, but personally I find it ironic that saving the planet’ could be used as a justification for the extinction of endemic rainforest species like the Woodlark Island cuscus.”

The Big Picture: Biofuels and Deforestation

Beginnings of an oil palm plantation. Courtesy of UNEP |

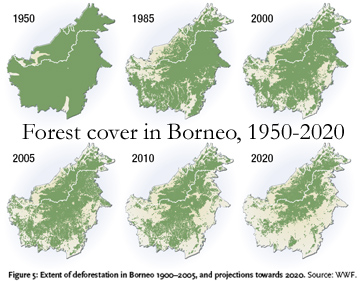

The situation of Woodlark Island is representative of much of Southeast Asia where large swaths of forest have been recently destroyed to produce biofuel crops. Two of the largest palm oil giants, Malaysia and Indonesia, have seen massive growth in palm oil production coupled with deforestation. In Indonesia oil palm plantations have expanded from 600,000 hectares in 1985 to more than 6 million hectares. This production is expected to reach 10 million hectares by 2010. Malaysia shares a similar story: palm oil production has risen from 151,000 metric tons in 1964 to 16.5 million metric tons last year. Currently, there is little suitable land left on the Malaysian peninsula, so future growth in the industry is expected to occur in Malaysian Borneo and Kalimantan. The biofuel industry is one of the few linked to global warming where it is believed money can be made quickly and easily. The USDA reports that in 1994 palm oil stocks were at 1.25, by 2006 they had climbed to 3.67. They have dropped in the last two years, but it is uncertain if that trend will continue.

PAst and projected forest cover in Borneo according to WWF |

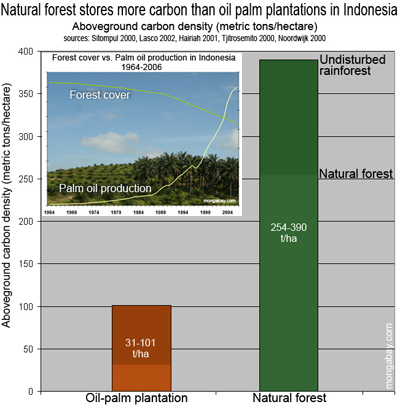

While the palm industry grows, questions have risen regarding its efficacy in fighting global warming. Research has shown that in a twenty year time span a palm oil plantation will store 50-90 percent less than the original forest. From this fact alone it seems that palm oil plantations built on what was once forest is actually contributing to global warming. When asked about forest versus palm oil, Dr. Norris pointed to a statement released this past March by several giants of the conservation movement—Greenpeace, Oxfam, RSPB, World Wildlife Fund, and Friends of the Earth—which states that the “dash for biofuels is ill thought out, lacks appropriate safeguards and could be creating more problems than it solves.” Ed Matthew of Friends of the Earth puts it even more succinctly: “It doesn’t seem possible that the [U.K.] Government could design a system for developing the biofuel industry that could actually make climate change worse but they seem to be managing it.” Current measures of climate change state that 20% of annual greenhouse gases is due to deforestation.

Carbon storage of oil palm plantations versus natural forests, based on various sources. From Oil palm does not store more carbon than forests |

Even if biofuels were better at storing carbon than forests, there would still be more to consider in the decision to clear forests. Currently, the planet is not only facing global warming, but a possible mass extinction, the sixth in Earth’s history. Estimates of extinction rates vary, but few biologists would deny that it is underway. In places like Southeast Asia, there is no question that palm oil plantations are contributing to a decline in species. For example, the U.N. Environmental Program recently estimated that by 2022, 98% of lowland forests in Indonesia will be gone, threatening innumerable species. Dr. Helgen describes the palm oil industry as having “devastating effect on wildlife in general and on endangered species, such as orangutans, in particular. Whereas primary and secondary forests in southeast Asia can support a tremendous wealth of animal and plant species, oil palm plantations usually support relatively few species by comparison, and usually only the common ones. One only needs to see a new oil palm plantation to understand why it does not support a great deal of biodiversity.”

|

Forest cover in Indo-Malaya (2000): 39% |

Biofuel production may cause even more general environmental degradation. Dr. Helegen lists a number of problems: “clearance for oil palm may be a veiled excuse for wholesale logging in many cases. Land is often cleared with fire to prepare it for plantation use, which can cause widespread burning of forests. Oil palm generates a lot of run-off and pollution, and creates new habitat for some invasive species (like rats). It also fragments forests and often fosters new opportunities for illegal hunting and trading of wildlife by plantation workers.” As well, biofuel production has caused deforestation in the Amazon by proxy. A large growth of soy production in Brazil, requiring a lot of land, has pressed ranchers and small-farmers even deeper into the forest. The soy industry has also built infrastructure in and around the forest, granting access to more slash-and-burning.

The environmental costs of the biofuel industry worldwide have been little reported in the U.S., even as congress begins to debate an energy bill that would include great support for the use of biofuels. Other nations, like the Netherlands, are attempting to enact legislation that would ensure the biofuels used in their countries met high environmental standards, including not contributing to deforestation or species loss.

Back to Woodlark Island

As seen from the conflict on Woodlark Island the palm oil industry can take its toll on the human community as well. Rumors have been flying around the island over the past week that Vitroplant Ltd. may be pulling out. So far, however, they are just that: rumors. Dr. Piyuwes states that amid these rumors, including an erroneous announcement over the radio, “the Vitrolplant agents convened a meeting at Masurina lodge” and displayed “interest to proceed.” While they wait to see how their demands are met, Dr. Piyuwes states that islanders have “promised to ensure this project does not arrive on Woodlark”. Unfortunately, Vitroplant Ltd. proved unavailable for response.

Where rainforest once stood in Malaysia now stands row after row of oil palms. Photos by Rhett A. Butler. |

In Woodlark Island’s situation, Dr. Helgen sees a bleak future for the whole country: “I have been worried that like Malaysia and Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, which supports some of the most remarkable wilderness areas on earth, might become heavily involved in oil palm production. I understand that plantation conversion has increased in eastern coastal areas of the country in recent years, and the plan to convert Woodlark’s forests to plantations confirms this as a valid fear.”

The islanders of Woodlark have spent a lot of time trying to draw international attention to this issue. Dr. Piyuwes believes such attention is essential since “we do not have money to fight the giant. We only hope for the support from the NGOs, and the mercy of the government to withdraw the project.” In the meantime, the islanders continue to wait, either for victory or a long struggle.