- As deforestation of tropical forests continues unhindered, one of the future hopes for these damaged ecosystems is regeneration in secondary forests.

- Some areas that were once slash-and-burned for cattle ranching or subsistence agriculture have been abandoned, allowing scientists to study the possibility of recovery in the rainforest.

- If anyone has a clear idea of the potential of secondary forests it is Robin L. Chazdon.

- Dr. Chazdon, a full professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Connecticut, has been studying the regeneration of secondary forest for over twenty-five years.

An Interview with Dr. Robin Chazdon an expert on Tropical Forest Regeneration

It is estimated that every day 80,000 acres of forest is destroyed. Such destruction affects innumerable species, indigenous peoples, and the climate. Habitat loss–especially in tropical forests–is one of the primary causes for the current extinction rate reaching between 1,000 and 10,000 times the historical background rate. Furthermore, this destruction often forces indigenous peoples from ancestral lands, causing them to either retreat further into the forest or be forced to confront the modern world. Finally, deforestation contributes to 20 percent of the world’s carbon, which is almost as much as the United States (still the world’s greatest CO2 emitter) contributes annually.

Tropical deforestation |

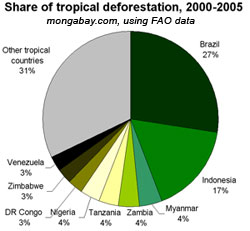

The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) estimated that between 2000-2005, 8.4 million hectares of forest were destroyed every year. This was a raise of 8.5 percent from the 1990’s. In the face of the glumness of such figures, this year brought positive news for the Amazon as it was estimated that deforestation fell by 31 percent from 2006. Whether this is a one-year fluke or a long-term trend remains to be seen. Deforestation in the Amazon and South America in general may be stagnating or even falling, but the tropical forests of South East Asia have never been so threatened. Palm oil plantations, illegal logging, and increasing demand for growing populations have caused several Asian countries to destroy their forests at astounding rates. The same study by the FAO found that while world deforestation had risen by 8.5 percent, Malaysia’s deforestation had gone up by 86 percent from the 1990’s to 2000-2005. Cambodia’s rate in the same time-period rose by 74.3 percent. And surprisingly, the country with the highest deforestation rate is no longer Brazil, but Indonesia. In 2006, 3 million hectares of forest were destroyed in Indonesia, much of this for logging and large-scale agriculture.

Dr. Robin Chazdon measuring a tree’s diameter in our 25 yr old plot |

As deforestation of tropical forests continues unhindered, one of the future hopes for these damaged ecosystems is regeneration in secondary forests. Some areas that were once slash-and-burned for cattle ranching or subsistence agriculture have been abandoned, allowing scientists to study the possibility of recovery in the rainforest. If anyone has a clear idea of the potential of secondary forests it is Robin L. Chazdon. Dr. Chazdon, a full professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Connecticut, has been studying the regeneration of secondary forest for over twenty-five years. She has published over 50 papers on tropical ecology, currently she serves as an active member of the Biotropica editorial board and is a member of the Bosques Project, which measures secondary forest recovery in Northern Costa Rica.

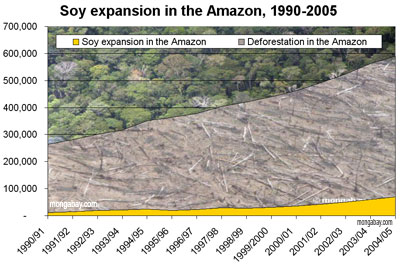

Soy expansion in the Brazilian Amazon, 1990-2005. Total deforestation and area of soybean cultivation across states in the Brazilian Amazon. Overall soybean cultivation makes up only a small portion of deforestation, though its role is accelerating. Further, soybean expansion and the associated infrastructure development and farmer displacement is driving deforestation by other actors. |

In an interview with mongabay.com, Dr. Chazdon talks of her hopes and fears surrounding the state of contemporary forests. While she sees the rise of large-scale agriculture as tropical forest’s greatest threat, she finds hope in her work on regenerating secondary forests and her frequent travels to Costa Rica, one of the world’s leading tropical nations in conservation. However, she stresses that forests may never recover from large-scale agriculture and even the tropics of Costa Rica face many dangers. Conservation of tropical forests still has a long road to go.

Dr. Chazdon is a member of the the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) which is having its 2008 meeting in Suriname.

INTERVIEW WITH DR. ROBIN CHAZDON

Mongabay: What is the focus of your research?

Chazdon: My research focuses on the regrowth of tropical forests following abandonment of agricultural land use. We are investigating how species of trees are recolonizing secondary forests and how trees, saplings, and seedling communities are changing over time.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in this area? What is your background?

Dr. Robin Chazdon with her crew of Costa Rican field technicians in a 30 yr old forest plot (Jeanette Paniagua, Juan Romero, and Bernal Paniagua) |

Chazdon: I have been studying tropical forest ecology since 1980, mostly focusing on the ecology of understory palms and their responses to fluctuating light availability. Growth of plants in the understory is limited by extremely low light conditions, but many species are able to utilize brief sunflecks when these occur. Studies of responses of plants to light variation led to a general interest responses of tree species to natural forest disturbances, such as canopy gaps created by tree falls. I became interested in forest regrowth during the 1980s as rates of deforestation increased in many tropical regions. I began by conducting inventories of secondary forests of different age and documenting the woody species found in different size classes. As I continued these investigations, it became clear that we needed to follow individual plants and entire communities over time to really understand the process of forest regrowth. In 1997, I obtained funding to establish long-term monitoring plots in four different sites on abandoned pasture that were 12-25 yr old. We now have ten years of data on trees, saplings, and seedlings in these plots and have expanded our research to more sites and to studies with collaborators in Chiapas, Mexico and Central Amazonia, Brazil. There is no shortage of regrowing areas of tropical forests, and much to learn about them.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students hoping to become conservation scientists?

Chazdon: I believe that conservation requires a broad understanding of biological diversity in all kinds of habitats, including areas strongly impacted by human activities. Even in the best-case scenarios, only 25% of land area is under formal protective status in the tropics. This means that most species of plants and animals are living in landscapes amidst agriculture, logging, forest fragmentation, urbanization, and small isolated reserves. Our biggest conservation challenge is to manage the landscapes we live in to enhance plant and animal life (including insects) while still permitting productive use of the land. Rather than focusing attention solely on conservation within reserves and protected areas, we need to look at the bigger picture of the entire landscape.

Mongabay: I see that you teach a course entitled ‘Current Topics in Biodiversity’, what are some topics covered in this course?

Chazdon: This graduate-level seminar course has concentrated on a range of topics including the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Biodiversity Synthesis (we read the entire document and discussed additional readings) and Measurement and Assessment of Biodiversity. This year we are focusing on Biodiversity in Human-dominated Landscapes.

Mongabay: What is you favorite place in the tropics?

Chazdon: I have a soft spot for La Selva Biological Station in northeastern Costa Rica, where I cut my teeth as a tropical biologist and where I have been fortunate to conduct research along with my husband and children during the past 20 years. I have really grown to love the young secondary forests of this region as well. They are exuberant expressions of plant growth and provide a rich supply of food resources for birds and mammals.

Mongabay: You have spent many years working in Costa Rica. Costa Rica is often described as one of the most progressive tropical nations in terms of conservation. Do you believe this to be an accurate description?

Chazdon: Costa Rica has truly been a leader in establishing national parks and protected areas and in using environmental service payments to promote conservation on private lands. The forestry law has been instrumental in protecting further destruction of valuable forests. Yet even with these advances, Costa Rica is facing a wood shortage and must now import wood from other countries to meet domestic demand. And currently, there are no incentives for allowing abandoned agricultural land to regrow naturally into forest, so farmers are either shifting their agricultural land use to or planting native or exotic tree species for reforestation incentives.

Mongabay:

What can other nations learn from Costa Rica’s example?

Chazdon: The national parks system in Costa Rica is an excellent example for other countries, but the costs are often too much to bear for poor tropical nations. Much of the financial support for these parks was generated from donations from other countries (especially the US) and from debt-for-nature swaps. Many countries are now following Costa Rica’s example in offering environmental service payments to farmers and landowners. These are positive developments.

Mongabay: Are there continuing risks to Costa Rica’s forests?

Chazdon: Absolutely. Illegal logging still occurs in many areas of Costa Rica. Fragmentation and climate change are also important threats to forests here as elsewhere in the tropics.

Mongabay: You are very involved with the Bosques Project. Could you describe this project in your own words?

Sapling of Virola sebifera (Myristicaceae) in a 25 yr old forest (this is a mature forest tree species and is dispersed by toucans and bats). It has rapid vertical growth and shows high levels of seedlings, sapling, and tree recruitment in second-growth forests. |

Chazdon: The Bosques project is investigating the dynamics of vegetation during tropical forest succession in Northeastern Costa Rica in the tropical wet forest life zone. We are monitoring growth, mortality, and recruitment of trees, saplings, and seedlings in ten long-term monitoring plots that span different ages (two plots are in old-growth forest). The eight secondary forest plots were all deforested and used for pasture before abandonment 12-35 yr ago. We measure annual changes in forest structure (tree density and size) and vegetation composition every year since 1997. We are also studying light conditions in the forest, soil characteristics, and seasonal patterns of leaf litter production, flowering, and fruiting. More recent studies are examining small mammal populations, seed dispersal, reproductive phenology, and functional traits of vegetation. The project has involved many collaborators and student projects.

Mongabay: In the nine years of studying regenerating secondary forests what have been some of your most surprising findings?

Chazdon: The most surprising finding so far is that the species composition and number of tree species is very slow to change within secondary forests. If you look at forests of different age, it appears that older forests have more tree species, but we are not seeing that same trend over time in the forests we have been following. Events very early in the regeneration process appear to determine the composition of the tree community and these effects persist for many years. We are also finding that most of the tree species in these forests are generalist species that can colonize secondary forests early or late, depending upon seed dispersal. Less than 20% of the tree species are specialists that can only colonize recently abandoned sites or late phases of forest regrowth.

Mongabay: Do you see hope for degraded tropical forests in the possibility of regenerating secondary forest?

The interior of a 10-yr old forest plot |

Chazdon: The hope is in the seedlings that are now present. We find similar numbers of species and similar composition of tree species in the seedling size classes in secondary forests compared to old-growth forests in the same area. As long as there are seed sources in the area and good populations of birds and bats, these animals are doing their job very well and dispersing seeds in the secondary forests. The seedlings are doing very well in these young forests, so they only need time to grow and become trees. This will take time, perhaps 50 yr or more, as it is now very shaded and growth is slow. In areas where seed sources are lacking, tree plantations offer some potential to “jump-start” succession and speed up the process. The best opportunities for forest regeneration are in areas adjacent to existing old-growth forest in buffer zones and biological corridors and where agricultural use of the land did not degrade the soil.

Mongabay: What do you see as the greatest threat to tropical forests?

Chazdon: Threats vary throughout the world, but I would say that the single greatest threat to tropical forests is the conversion of forests to large-scale industrial agriculture (such as oil palm, sugar cane, and soybean). Production of crops for biofuels poses such a threat now in many countries. Industrial agriculture is a major threat because once this conversion occurs, future forest recovery is seriously compromised and traditional (more biodiversity friendly) land uses are marginalized. In contrast, small scale agriculture amidst remnant patches of forest allows many species to persist in the landscape and is far more compatible with conservation.

Mongabay: Do you believe climate change to be a significant threat to the tropics?

Chazdon:

Yes, there is strong evidence that climates are changing in tropical regions and that these changes are affecting forest species. Severe droughts and higher mean air temperatures are already changing rates of tree mortality in addition to increasing frequency and severity of forest fires. Hurricanes (and resulting flooding) may also become more frequent due to global warming, causing large-scale disturbances in tropical forests.

Mongabay: Having worked so closely with regenerating forests what general characteristics does a ‘healthy’ tropical forest have?

Chazdon: Healthy forests have diverse populations of birds, mammals, and insects. These animals are critically important for pollinating plants and for dispersing seeds and for keeping populations in check. A forest is more than just the trees.

Mongabay: What must be done to ensure conservation of tropical forests?

Chazdon: We must learn to value tropical forests for all that they provide, including the environmental services of carbon sequestration, hydrological protection, biodiversity protection, and scenic value. If we, as a society and culture, can learn to value forests, then they will be conserved, as it will clearly be in our best interests to conserve them. Education is critically important, as early in life as possible. It is also important to teach people about the interconnections between tropical forests and their daily lives. These connections are all around us, in the tropical fruits we like to eat, the coffee and tea we like to drink, the tropical woods we like to use, and the migrant songbirds that breed in our backyards during the summer. It’s all connected.