Amazon plant diversity still a mystery

Amazon plant diversity still a mystery

By Jeremy Hance, special to mongabay.com

October 21, 2007

Recent study of unknown Amazonian flora proves just how much of the region is still unknown to science

The Amazon is one of the few places on the earth that still evokes an accurate sense of mystery. While the Taiga, Antarctica, and Sahara may compare to the Amazon in wilderness size, none hold the same mystique of unknown species. It is believed that one third of the world’s species inhabits this tropical rainforest. The only region comparable in mystery (though not in species) may be the world’s oceans.

While the Amazon is being threatened by numerous industries—including cattle, logging, agriculture, and now increasing pressure from the burgeoning bio-fuel industry—much of this vast tropical forest has never been properly explored by scientists. One of the great gaps in Amazonian knowledge is the cataloguing and taxonomy of plants. In a recent study, researcher Michael Hopkins estimated the distribution of unknown flora in the Amazon. His research found that plant biodiversity has long been underestimated and that “there are probably at least 3 times more plant species in Amazonia than are currently known”. It is estimated that about 500,000 plant specimens in the Amazon have currently been collected.

Aerial view of the Amazon rainforest canopy. More than 300 species of trees can be found in a single hectare of Amazon forest. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

These results predicted far higher diversity than preceding studies. Dr. Hopkins states that the main difference between his study and others is that he looked at the Amazon’s gamma diversity—in other words he measured the overall biodiversity in a large geographic area, namely 10,000 square kilometers. Past studies estimated botanical biodiversity in the Amazon using a method called alpha diversity, focusing only on a distinct group of species in smaller areas—for example one study counted all trees above ten centimeters in a hectare. “I don’t think it’s surprising that the pattern is rather different,” Dr. Hopkins comments, “I’m certainly not saying that other people’s maps of the distribution of alpha diversity are wrong!”

In order to estimate the amount of unknown flora in the Amazon, Hopkins had to begin with past collections. This presented several problems. First was the low density of such collections, secondly most of the plants came from very specific areas, i.e. those near cities, roads, and rivers. Finally, georeferencing (locations for the species collected) was not done for plants collected over fifteen years ago, and even current georeferencing could not be relied on. These difficulties make any estimate problematic, and Dr. Hopkins is quick to begin any discussion about his study’s predictions with “if the model is approximately right

”

And if it is, then there are four large regions in Amazonia that are in desperate need of scientists. Each of these areas is characterized by very little knowledge of the region’s flora, but a high probability of great botanical diversity: lowland Colombia; western Brazilian Amazon in the state of Amazonas; north-western Brazil incorporating the states of Amazonas, Roraima, and Para; and the south-eastern Amazon, mostly in Para. He believes this last region is the most intriguing for “it’s in an area traditionally considered rather undiverse, but the model predicts high diversity”. This region is also the most threatened of the four: the Transamazonica highway passes through here and in the Amazon, wherever there are roads there is deforestation.

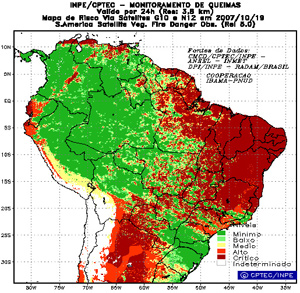

While deforestation poses a great threat to the Amazon’s known and unknown species, Dr. Hopkins states that the issue which worries him most is sudden desertification: the Amazon undergoes what he describes as a “flip-over climate”. He states that “if the region does dry out [

] a devastating widespread fire could change the very nature of the forest cover from one year to the next. I do think this is a distinct possibility within the next 50 years or maybe less.” Already this year, there have been many reports of large fires in the Amazon. Such fires are usually man-made; settlers burn illegally to clear the forest for cattle or agriculture. These fires often get out of control and spread far beyond their intent.

Fire risk in the Amazon and surrounding region on October 18, 2007. Courtesy of INPE. |

Working as a taxonomist in an Australia-sized biome that is both widely threatened and terribly understudied is no easy task. But it’s even more difficult when the area has received, surprisingly, very little outside support and interest. Michael Hopkins asks, “Where are the taxonomists? Where are the collecting programs? Where are the students? Where is the investment? Take a look at any of the international bodies that invest in taxonomy, and divide the dollars by the number of species, and you will see that Amazonia is already a desert in this respect!” He sees two reasons for the lack of researchers on the ground. The first is Brazil’s bureaucratic hoops that are especially hard for researchers; Hopkins calls it their “Bioparanoia” and notes that other Amazonian nations have a far better record of plant taxonomy. The second is that recent scientists unfortunately don’t see taxonomy as “academically sexy”. When it comes to studying flora, “Amazonia has been basically abandoned over the past 15 years”. This lack of hard knowledge creates deep problems when it comes to making conservation decisions. Hopkins states that such choices are often based on planning that “isn’t much better than guesswork”.

Despite the frustrations, Hopkins sees possibility and hope: “there is a window to do decent collecting, decent training, and hence decent taxonomy, and one hopes if time remains, decent conservation planning.” His greatest hope lies in “training Amazonians to want to know Amazonia better, especially training local communities to be the dynamos demanding better knowledge.”

Michael Hopkins’s latest study has given us an idea of how much may be out there. Now, it’s a matter of finding it, naming it, and saving it.

CITATION: Michael J. G. Hopkins (2007). Modelling the known and unknown plant biodiversity of the Amazon Basin. Journal of Biogeography. Volume 34 Issue 8 Page 1400-1411, August 2007.