Frog killing diseases worse than thought in California

Frog killing diseases worse than thought in California

mongabay.com

August 6, 2007

The deadly fungal disease that is killing amphibians worldwide can likely be spread by sexual reproduction reports a new study published in the early online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The findings suggest that protecting frogs and other amphibians from the pathogen will be more complicated than previously believed.

Analyzing the DNA of the Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis among mountain yellow-legged frogs in the California Sierra Nevadas, researchers led by Jess Morgan found that when the fungus reproduces sexually, it creates spores that can last more than a decade.

“That could make this pathogen a harder problem to defeat. As a resistant spore, the fungus could be transported by animals, including humans or birds, or lay dormant in an infected area until a new host comes along,” said John Taylor, a University of California at Berkeley professor of plant and microbial biology who was the principal investigator of the study.

Panama’s golden frog (Atelopus zetecki) is highly threatened by the killer chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), an infectious skin disease now found in frog populations around the world. |

To better understand how the fungus spreads and reproduces, the researchers sought to determine which of two competing hypotheses on the origin of the disease.

“If the fungus was recently introduced to an area, the researchers would expect to find a single genotype that had spread by clonal reproduction. If, however, the fungus is endemic to a region, they would expect to find diverse genotypes resulting from a long history of association that provides enough time for isolates to diverge through mutation and genetic recombination,” explained a statement from UC Berkeley. “If the fungus is endemic to a region, the animals in the area would normally be resistant to its destructive effects because they would have co-evolved together. However, biologists theorize that changes to the environment – from global warming to pollution from agricultural chemicals – could make native frog populations susceptible to a pathogen with which they’ve previously co-existed.”

The study found that neither epidemic spread nor endemism alone could explain the decline of the California frogs.

“We found sites dominated by a single fungal genotype, which suggests a recent spread of the pathogen through clonal reproduction,” said lead author Jess Morgan, who was a UC Berkeley post-doctoral researcher working with Taylor at the time the study was conducted. “But this study also provides the first evidence of genetic recombination in B. dendrobatidis, which results in multiple, related genotypes and signals that sexual reproduction is occurring.”

Shown is a mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa) at Milestone Basin in Sequoia National Park. Credit: Photo by Vance T. Vredenburg, UC Berkeley |

“Up until now, people thought the movement of this pathogen was mainly via infected frogs, so such measures as restrictions on the pet trade were put in place,” said Morgan, who is now a research scientist at the Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries in Queensland, Australia. “If, in fact, this fungus produces resistant spores, people could be unwittingly transferring this pathogen around the world from dirt on our shoes or car tires. But spores could also hitchhike on the feathers of birds for quick transport across mountain ranges.”

Researchers in other parts of the world have voiced similar concerns, and have even blamed scientists for inadvertently worsening the outbreak of the disease in some areas by carrying spores on their boots. The new study found that some California sites contained two similar populations of fungi, suggesting that fungi spread was somehow facilitated by humans.

“If we confirm that spores are a factor, then there may be precautions we can take to contain their spread,” said Morgan. “This could involve cleaning shoes before moving from one infected site to another. Some fungi produce spores during certain times of the year. If that is the case with this fungus, we could consider restricting public access to infected sites during those times.”

Further, because the spores can survive for long periods of time, reintroduction of endangered frogs into their original habitat may not save them from infection.

“Within two years, the healthy frogs we introduced would become infected with the fungus and die,” said study co-author Roland Knapp, who had tried to reintroduce mountain yellow-legged frogs in remote lakes in the Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks and the John Muir Wilderness. “It’s a stunning thing to see. One year, there is no obvious evidence of the disease, the next year, we’d come back to see hundreds of dead or dying frogs, and then the following year, they’d all be gone.”

While the study is discouraging for frog conservation efforts, it does provide insight on the chytridiomycosis epidemic which has killed millions of amphibians worldwide.

|

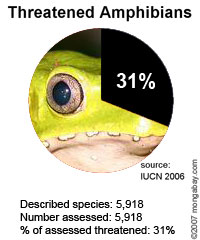

According to the Global Amphibian Assessment, a comprehensive status assessment of the world’s amphibian species, one-third of the world’s 5,918 known amphibian species are classified as threatened with extinction. Further, more than 170 species have likely gone extinct since 1980. Scientists say the worldwide decline of amphibians is one of the world’s most pressing environmental concerns; one that may portend greater threats to the ecological balance of the planet.

“This frog used to be the most abundant amphibian, and perhaps the most abundant vertebrate, in the whole Sierra Nevada,” said Knapp. “Over the past 30 years, it has disappeared from up to 95 percent of its historic range, and its absence is impacting other organisms. Garter snakes that used to prey on these frogs are now declining. The frog’s decline is leading to an unraveling of a high-elevation ecosystem.”

CITATION: Jess A. T. Morgan et al. (2007). Enigmatic amphibian declines and emerging infectious disease: population genetics of the frog killing fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. PNAS early online edition August 6, 2007.

Related articles

Global warming may be key factor in frog deaths. Three papers published in this week’s issue of the journal Nature debate the proximate causes for the global decline of amphibians, but nonetheless reveal mounting concerns among scientists over the continuing disappearance of frogs, salamanders, and their relatives.

Scientists find possible cure for global amphibian-killing disease. Scientists have discovered a possible treatment for the fungal disease that has killed millions of amphibians worldwide. Presenting Wednesday at the General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in Toronto, Professor Reid N. Harris at James Madison University reported that Pedobacter cryoconitis, a bacteria found naturally on the skin of red-backed salamanders, wards off the deadly chytridiomycosis fungus, an infection cited as a contributing factor to the global decline in amphibians observed over the past three decades.

Bad news for frogs; amphibian decline worse than feared. Chilling new evidence suggests amphibians may be in worse shape than previously thought due to climate change. Further, the findings indicate that the 70 percent decline in amphibians over the past 35 years may have been exceeded by a sharp fall in reptile populations, even in otherwise pristine Costa Rican habitats. Ominously, the new research warns that protected areas strategies for biodiversity conservation will not be enough to stave off extinction. Frogs and their relatives are in big trouble