Amazon deforestation rate falls to lowest on record

Amazon deforestation rate falls to lowest on record

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

August 10, 2007

Deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon for the previous year were the lowest on record, according to figures released by INPE, Brazil’s National Institute of Space Research.

Preliminary estimates show that between August 1, 2006 and July 30, 2007, some 3,707 square miles (9,600 square kilometers) of rainforest were cleared, a 31 percent drop from 2006 when 5,419 sq ml (14,040 sq km) were lost (2006 figures were recently revised from 13,100 sq km). Deforestation rates have fallen sharply — 65 percent — since 2004 when 10,590 sq mi (27,429 sq km) were destroyed.

“INPE’s preliminary estimate that deforestation in Amazonia in 2007 is 9,600 km2 plus or minus 10 percent. This estimate will be confirmed by the official PRODES figures from 2007, which we hope to announce in late November, before the Bali [climate] conference,” INPE’s Director General, Dr.Gilberto Camara, told mongabay.com. “These estimates are a cause of rejoice to us all. This is the lowest deforestation rate since mid-70s.”

The latest figures are based on analysis of 213 images of LANDSAT satellite and 90 CBERS images. Brazil’s satellite monitoring system is among the most sophisticated in the world.

Analysts say the drop in deforestation rate is due to economic trends, mainly lower prices for grains and beef, while the Brazilian government credits its own aggressive law enforcement efforts for cracking down on illegal forest clearing. Brazil has also dramatically expanded its network of protected areas in recent years, setting aside more than 100 million hectares of the Amazon basin from development since 2002.

|

A turning point in Brazil’s law enforcement efforts in the Amazon may have been the 2005 slaying of American nun Dorothy Stang who was gunned down by thugs hired by development interests. Stang had fought for the rights of the rural poor, making her an adversary of loggers and ranchers in the Brazilian state of Para. Following her assassination, the government sent in troops to restore order and announced the establishment of several giant rainforest reserves. Stang’s killers were eventually charged with the crime and imprisoned.

Brazil now has some 173 million hectares of forest, an area nearly three times the size of France, under some form of protection, giving it the largest protected areas system in the world. Nevertheless some scientists believe the Amazon may be approaching a critical tipping point, with climate change putting the basin at risk of significant shifts in rainfall and temperatures. Some models project that temperatures in the Amazon could climb by as much as 8 degrees Celsius by 2100, spurring forest fires and drought while exacerbating “savannization “, whereby rainforest is replaced by savanna.

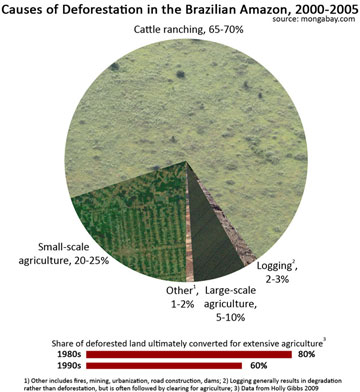

Clear-cutting in the Amazon. The Amazon is Earth’s biggest rainforest, but since the early 1970s about 650,00 square kilometers (250,000 square miles), or 18 percent of the forest area — have been destroyed. In recent years road construction, clearing for agriculture (especially soybeans) and cattle pasture, and logging have been responsible for most forest loss. |

“There are several other factors that are pushing the Amazon towards a drier future, including fresh evidence that cattle ranches and pastures are less capable of generating rain than the forests they replace because they put less water vapor into the air–soy fields are even worse,” said Dr. Daniel Nepstad, director of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program and a leading expert on the Amazon, in an interview with mongabay.com. “On top of these changes in the vegetation itself we have rainfall-inhibiting smoke and the prospect of sea temperature changes–not just el Niño… but the North Atlantic tropical anomaly like we saw in 2005 when we had record drought and record fires in the Amazon. The likelihood of that type of anomaly will increase with global warming.”

“When we put all this together we come up with a very bleak outlook for the Amazon rainforest. I don’t have the final numbers, we’re running these right now, but it’s not out of the question to think that half of the basin will be either cleared or severely impoverished just 20 years from now.”

The above pie chart showing deforestation in the Amazon by cause is based on the median figures for estimate ranges. Please note the low estimate for large-scale agriculture. Between 2000-2005 soybean cultivation reesulted in a small overall percentage of direct deforestation. Nevertheless the role of soy is quite significant in the Amazon. As explained by Dr. Philip Fearnside, “Soybean farms cause some forest clearing directly. But they have a much greater impact on deforestation by consuming cleared land, savanna, and transitional forests, thereby pushing ranchers and slash-and-burn farmers ever deeper into the forest frontier. Soybean farming also provides a key economic and political impetus for new highways and infrastructure projects, which accelerate deforestation by other actors.” |

While Nepstad’s projections are dire, he, like some other scientists are conservationists are hopeful that the tide is turning in the Amazon. Nepstad believes that increasing international pressure for sustainbly-produced products could help drive better management of the Amazon and other forests.

“One very recent development is that commodity markets are demanding greater legality and greater stewardship for the entire production chain.” Nepstad continued. “Meanwhile the international finance corporation (IFC), ABN Amro, Rabobank, and several other creditors are beginning to attach environmental conditions to their loans.”

These shifts could ultimately determine the fate of the Amazon, the planet’s largest and most biodiverse rainforest.

“It is very important not to succumb to the fatalism that so often affects discussions of Amazonia,” said Dr. Philip Fearnside of the National Institute for Research in the Amazon. “What happens depends on human decisions.”

RELATED ARTICLES

|

Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon?

(6/6/2007) John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Alianca da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Alianca’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon.

|

Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

(6/3/2007>) The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale, the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belem, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.

Will Amazon drought worsen in 2007?

(5/29/2007) Contrary to popular belief, the Amazon rainforest is not rainy year round. Further from the equator, rainfall is more seasonal, with dry periods that sometimes last for months.

|

U.S. ethanol may drive Amazon deforestation

(5/17/2007)> Ethanol production in the United States may be contributing to deforestation in the Brazilian rainforest said a leading expert on the Amazon. Dr. Daniel Nepstad of the Woods Hole Research Center said the growing demand for corn ethanol means that more corn and less soy is being planted in the United States. Brazil, the world’s largest producer of soybeans, is more than making up for shortfall, by clearing new land for soy cultivation. While only a fraction of this cultivation currently occurs in the Amazon rainforest, production in neighboring areas like the cerrado grassland helps drive deforestation by displacing small farmers and cattle producers, who then clear rainforest land for subsistence agriculture and pasture.

|

Rainforests face myriad of threats says leading Amazon scholar

(10/16/2006)> The world’s tropical rainforests are in trouble. Spurred by a global commodity boom and continuing poverty in some of the world’s poorest regions, deforestation rates have increased since the close of the 1990s. The usual threats to forests — agricultural conversion, wildlife poaching, uncontrolled logging, and road construction — could soon be rivaled, and even exceeded, by climate change and rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Understanding these threats is key to preserving forests and their ecological services for current and future generations. William F. Laurance, a distinguished scholar at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and president of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) — the world’s largest scientific organization dedicated to the study and conservation of tropical ecosystems, is at the forefront of this effort.