- Wildlife conservation in Afghanistan?

- Adventures in conservation: protecting wildlife in Afghanistan

- An interview with Dr. Alex Dehgan, Afghanistan Country Director for the Wildlife Conservation Society

- Afghanistan’s recovery effort drives poaching of rare wildlife, but conservationist says protection efforts could improve stability.

Few people associate Afghanistan with wildlife and it would come as a surprise to many that the war-torn, but fledging democracy is home to snow leopards, Persian leopards, five species of canid (wild dog), Marco Polo Sheep, Asiatic Black Bear, Brown Bears, Striped Hyenas, and numerous bird of prey species.

While much of this biodiversity has survived despite years of civil strife, Afghanistan’s wildlife faces new pressures from the very people who are charged with rebuilding the country: contractors and the development community are driving the trade in rare and endangered wildlife. This development, coupled with lack of laws regulating resource management and growing instability, complicate efforts to protect the country’s wildlife.

Working to address these challenges is Dr. Alex Dehgan, Afghanistan Country Director for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). WCS is working to implement the Afghanistan Biodiversity Conservation Program, a three-year project funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) to promote wildlife and resource conservation in the country.

Dr. Alex Dehgan with a leopard pelt during a wildlife trade survey in Afghanistan. Photo Credit WCS |

Dehgan believes that protecting Afghanistan’s resources is key to the recovery process and will help improve stability and security, especially in areas where military intervention has fallen short and government presence is sometimes non-existent.

“Environment is security,” he explained. “To date, it is clear that more military weapons, or training for the army alone won’t result in peace in Afghanistan. One essential part of the security equation is better management of natural resources. Habitat degradation affects both the wildlife and the people. Where 80 percent of the population is dependent on natural resources, the same actions that allow for the survival of wildlife also permit the survival of the Afghan people on this fragile landscape. When the environment fails to support the people because of environmental degradation, it may generate conflict, or exacerbate existing ones, which in turn leads to further degradation in a downward vortex towards instability.”

In a July 2007 interview with mongabay.com, Dehgan discussed some of the unique challenges of conservation work in places where mine fields are unmarked and remoteness necessitates that conservation workers also be trained as medical first responders.

AN INTERVIEW WITH ALEX DEHGAN

Mongabay: What brought you to Afghanistan?

Dehgan: The challenge of working in a post-conflict country, the opportunity to build conservation from the ground up, the chance to work with some of the most hospitable, intriguing, and courageous people in the world in Afghanistan, and at the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Mongabay: How much biodiversity is left in Afghanistan or are you mostly looking to protect landscapes and habitat and hope that animals will return?

Dehgan: There is substantial biodiversity left in Afghanistan, and even more left to be discovered that was never known. Afghanistan has been rarely surveyed. Of the global natural history museums, only 1 has more than 10 specimens from Afghanistan, and that from a single survey conducted in the 1960’s. Since the 1970’s, there has been little scientific work. Biodiversity in Afghanistan has suffered as a result of the nearly 3 decades of conflict, but there are places in Afghanistan that are still very wild, and worthy of preservation, and we are discovering more and more that we must act now to protect them.

Steppe eagle in Afghanistan. Photo Credit: Alex Dehgan |

At one time, Afghanistan had as many felid species (cats) as that of the entire African continent, and depending on whether the Asiatic Lion was ever in Afghanistan, perhaps even more. At the moment, there are still 9 felid species compared to 11 for the African continent. Due to hunting and the fur trade, some of these species have gone extinct. We have discovered that Afghanistan still possesses important populations of snow leopards (perhaps 100-200), Persian leopards, Marco Polo Sheep that have impressive curling horns that measure nearly 2 meters (over 6 feet!) along the curve, Markhor with dual unicorn horns that may reach a meter long, Asiatic Black Bear, Brown Bears, Striped Hyenas, five species of canids, the onager, and numerous spectacular eagles, falcons, and other bird species.

The Asiatic Cheetah, one of the rarest felids in the world, may still be present in Afghanistan, despite proclamations of its extirpation. The Asiatic Cheetah, which was once distributed through the middle east, is reduced to a population of only 60-100 individuals in Iran (where WCS also works), a number which rapidly approaches the arbitrary benchmark of no return for many small populations due to limited genetic gene pools, increasing difficulty finding mates, and extinction risks from chance events like a storm or disease. Although it was last seen in the wild in the 1950’s in Afghanistan, with a pelt photographed in the 1970s (only a single pelt is in the collections of all of the global natural history museums, the last collected in the 1940’s), WCS has found a pelt in Kabul from a cheetah that was supposedly hunted within the last year in Afghanistan. We are testing the skin sample to determine whether this animal was obtained in Iran, Africa, or perhaps even Afghanistan. Afghanistan is remote enough, and unknown enough, that many species of flora and fauna remain for WCS and Afghan scientists to find.

The question remains how long we have to document Afghanistan’s biodiversity, given the increasing instability within the country and the limited reach of environmental laws beyond the cities, and even within them. One major impact on wildlife comes from the people who are in Afghanistan presumably to assist it. Our systematic surveys of the fur shops, military markets, and factories this year have indicated that the development and contractor community, among other internationals present in Afghanistan, fuel wildlife trade in Afghanistan, including products made from snow leopard, wolf, fox, lynx, Persian leopard, leopard cat, and other animal skins. This trade is putting vulnerable populations at even greater risk, and is illegal under national and international laws. A factory that WCS visited was busy filling an order for 100 lynx comforters that could single handedly decimate the lynx population in Afghanistan. Another contractor involved in opium eradication efforts purchased a snow leopard comforter. With only an estimate population of 100 snow leopards left in the country, the contractor single-handedly had an effect on one of the most endangered species in the country. Any importation of these goods into the US would involve the violation of Afghan law, US law, and the international Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora.

The irony of wildlife trade is that many of the people who are buying these skins have come to Afghanistan to help rebuild the country, yet are destroying one important aspect of its identity. WCS has started a major effort to address this problem in partnership with the US Agency for International Development, US State Department, US Department of Defense, foreign embassies (such as Sweden and Indonesia), and the Afghan government, focused on the dual approach of education and enforcement.

Mongabay: Level II or Level IV soft body-armor? Seriously though, there must be unusual risks associated with working in a war-torn country. How is conservation in Afghanistan different from other parts of the world?

Dehgan: There are a unique set of challenges in Afghanistan that are unknown perhaps in other parts of the world. They extend beyond the usual issues faced in doing conservation. Afghanistan is the third most heavily land-mined country in the world, but what is unique about Afghanistan is that there are many areas where the locations of those mine fields are unknown. The brutal nature of the war led the Russians, for instance, to mine vast areas through butterfly mines dropped from helicopters. Many mined areas were never mapped. One of the most frightening experiences I have had in Afghanistan is when we were driving in an old riverbed when the road was lost and realized we were in the middle of a minefield, without a clear delineation of boundaries.

Located on the southern slopes of the Hindu Kush mountains in the northeastern part of the country, rugged Nuristan is home to a number of charismatic wildlife species. Photo by Dr. Ahmad Farid |

The war also destroyed much of Afghanistan’s infrastructure. Roads that weren’t destroyed by war were destroyed by neglect, assisted by raging rivers, earthquakes, rockfalls and landslides. Much of Afghanistan is very difficult to access — some of our field sites take days or weeks to reach by horseback, donkey or yak, assuming river crossings can be made, or the snow levels on 4,000 meter passes isn’t too high. Finally, the international nature of the insurgency has meant that there are certain areas we work through proxy only, since it is too dangerous to go as outsiders (and this includes Afghans from other provinces). We train teams made up of Afghan veterinarians, scientists, and community members from the region — including hunters, the best trackers — to carry out the surveys in these remote and challenging areas, with the provisio however that safety comes before data.

Further, we don’t wear body armor, drive around in armored vehicles, or carry guns to lower our profile and avoid classification as a target of interest. The recent events has made this more challenging, however, as the nature of the war has become asymmetric, meaning NGOs have become targets. The most important protection we bring to our project is transparency and respect for the local people and culture. That aside, we do invest considerably in preparedness for the extremely remote environments and challenging situation we find ourselves in. All of our staff have been trained as medical first responders, and certified by the Australian government. We have developed plans and contingencies to be able to evacuate someone from the top of a remote glacier in the Pamirs, and we work in places where we don’t need armored vehicles.

Mongabay: What are logistics like? Can you get the resources and supplies you need?

Dehgan: The logistics of working in Afghanistan are some of the most challenging in the world. Afghanistan is characterized by incredible mountain ranges that push into the heart of the country, and they provide us with serious challenges. There are no roads, so WCS survey teams will travel for weeks by yak or horse over multiple high mountain passes. River crossings may be dangerous, and the water levels can wipe roads off the maps, not to mention our horses, supplies, or even vehicles. We travel among some of the most interesting peoples of the world, the Wakhi, who are Ismaeli’s who follow the Aga Khan, and the Kyrgyz, who are Turkish speaking nomads, the Hazara, the remnants of Gengis Khan’s armies in central Afghanistan, and the Nuristanis —people who inhabit the land of the enlightened, who have their own language, culture, and until a hundred years ago, their own religion.

Silk Road in the Little Pamir. Photo Credit: Don Bedunah |

All of our scientific supplies have to be airlifted from the United States and Europe, which in itself poses challenges since all things have to be planned with great detail in advance, and you can’t take a trip to the neighborhood store to get replacement equipment. Our vehicles travel with a year of spare parts, medical kits, and redundant communication systems, and have been specially designed for the environment of Afghanistan in mind through high altitude compensators, multiple oil filters to handle dust, dual gas tanks and batteries, and in the off-chance we go over a small anti-personnel mine, ballistic blankets along the bottoms of the vehicles.

Mongabay: How well are efforts being received locally? Are Afghans signing up to be park rangers? It seems like they might have a lot to offer with their knowledge of the landscape and wildlife.

Dehgan: We have benefited from tremendous support from the Afghans — both at the local level and within the highest levels of the government. Afghanistan’s wildlife is part of their very identity. For people who have spent much of the last 20 years as refugees in various countries, connecting with those elements of their country is remarkably important. We have found petroglyphs depicting wildlife in our proposed protected areas that are thousands of years old. People’s houses are decorated with paintings of Marco Polo sheep and ibex in these areas, and the horns of these animals decorate the entrances.

Conservation Education in Afghanistan. Photo Credit: Inayat Ali |

Moreover, no solution could be made without the support and participation of the local communities. One quarter of our work involves engaging the communities. Another involves training and capacity building. We draw from three sources for our courses: the government, which represent Afghanistan’s present, recent university graduates who represent Afghanistan’s future, and finally, the local communities, who teach us as much about the natural history of these species as we to them about our scientific methodologies. Our training program involves short courses, opportunities to participate in international conferences (for the first time in the history of the Society for Conservation Biology, Afghanistan sent three scientists to the conference in South Africa this year), and study tours, and for the best and the most promising, graduate study abroad. However, the core of our work in building capacity involves taking Afghans into the field along with our field scientists to give Afghans opportunities that they haven’t had in the university. For some areas, like Nuristan which is on the Afghan-Pakistan border, we work with proxy teams that conduct surveys for us under our mentorship. Many of the most valuable members of our teams are hunters from the local communities who are now working for conservation.

Mongabay: Do you believe that the establishment of national parks and other protected areas can help bring peace and stability to the country?

Dehgan: Environment is security. To date, it is clear that more military weapons, or training for the army alone won’t result in peace in Afghanistan. One essential part of the security equation is better management of natural resources. Habitat degradation affects both the wildlife and the people. Where 80 percent of the population is dependent on natural resources, the same actions that allow for the survival of wildlife also permit the survival of the Afghan people on this fragile landscape. When the environment fails to support the people because of environmental degradation, it may generate conflict, or exacerbate existing ones, which in turn leads to further degradation in a downward vortex towards instability. What we need is a new paradigm of security that takes us out of the concepts that were developed out of the cold war, which have been adapted to the “long war” (aka, the War on Terror), but brings together different axes that we have historically kept separate: environmental degradation, development, disease, and national security.

Color in a brown land. Photo Credit: Alex Dehgan |

Further, the power in Afghanistan is frequently not in the center, but is diffused through multiple poles. WCS is working to strengthen the center by developing effective national laws and policies, while developing enforcement through governance structures and conservation education at the community level. By giving communities tools within the historical framework of power at the local level, we may improve the protection of the environment, and create processes that will help Afghanistan, a country at the crossroads of one of the earth’s most volatile regions, become more secure. Without the incredible foresight of the US Agency for International Development to fund our project, we wouldn’t be able to have this opportunity to help in stabilizing Afghanistan.

Mongabay: How did your background, both academic and professional, prepare you for helping to establish Afghanistan’s first protected areas system? You have a law degree. Does that help in conservation?

Dehgan: Conservation solutions involve more than just science, but also being able to translate science into the policy arena. Scientists that fail to make their research relevant through in the policy process are effectively failing their obligations to society which funds their research and salaries. Most scientists, including many involved in conservation, are disinterested in the policy process, or fail to understand its differing needs. Watching scientists testify before Congress makes me believe that most scientists, even those interested in affecting policy, cannot connect with policymakers, and most policymakers fail to understand the scientific data and the method that generates it.

I wanted to address this gap between science and policy by looking to train in both areas and obtained a law degree and a doctorate in evolutionary biology. My scientific training provided me with a framework for asking questions and evaluating data. My legal studies and policy work help me translate knowledge into action.

Mongabay: More generally, what advice can you give students wanting to pursue a career in conservation? Are there specific degrees they should consider or is conservation so multi-faceted today that one could approach from a number of different disciplines?

Dehgan: Conservation involves many different disciplines, and multiple pathways to involvement. There is no single path, but I would recommend the following advice to a young conservationist entering the field:

Think Multidisciplinary. It is not enough to understand a single field, or a single species, but a conservation biologist must also understand how to translate that information, and how different fields may impact the implementation of your understanding.

Rely on Data. Conservation has to be based on data, rather than rhetoric. Scientific data provides a foundation for the policy options that need to be taken. Without such data, we have no basis for advocating one policy option (conservation for instance) over another (deforestation). This applies whether you are working on biology or economics. We must start with the data, and if it isn’t there, we must collect it. This in part is why I appreciate the Wildlife Conservation Society so much, as they start from this point.

Be Relevant. We have to make our results available, whether we study charismatic species like lemurs or cheetah, or invertebrates, to make others understand why pursuing a particular question is so important, and why societal funding for science must continue.

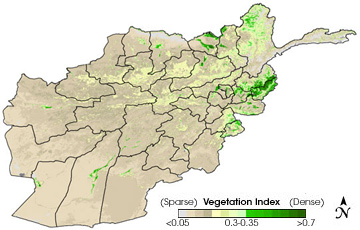

This map shows Afghanistan’s vegetation index for August 13-28, 2005. Deep green indicates dense vegetation, and earth tones indicate sparse vegetation. Most of the country is sparsely vegetated. (Map courtesy FEWS NET) |

Be Novel and Take Risks. Focus on those species or test ideas that are not part of the current fad. Like many other fields, conservation biology suffers badly from fads and trends that are more of an exercise in theoretical futility rather than tying the theory to the biology of the species that matter. Novel ideas encourage creative independent thought, and they allow for the field to advance, rather than stagnate. It is important to also take a risk, particularly when starting out, since this will distinguish you from the rest of the crowd, and allow you to demonstrate independence.

Be Policy Savvy. Scientists have to understand how to translate science into policy. That doesn’t mean advocacy, but making sure that the data is supporting the correct policy options. It also calls for an understanding of the differences between the fields.

Mongabay: Outside of Afghanistan, what are you other areas of interest?

Dehgan: My passion are prosimians, particularly lemuriformes (lemurs and lemur-like animals). One of the most enjoyable parts of my life was spending 3 years living in the southeastern rainforests of Madagascar trying to understand the question of why certain animals go extinct after environmental change, while others are able to survive.

In addition to Madagascar and lemurs, I truly enjoy most of the world’s rainforests and coral reefs (in many ways, these are rainforests taken underwater, except now you have the ability to fly as a researcher). I am keen to do a rapid assessment survey of all of the world’s major rainforests and coral reefs to bring attention to their plight and to help inspire the next generation of conservationists, much like the great biologists like Paul Ehrlich and Tom Lovejoy inspired me.

Mongabay: What can people do here in the United States or other parts of the world, to help conservation efforts in Afghanistan?

Dehgan: They can write to their congressmen in support of WCS’ program in Afghanistan to ensure that support for WCS Afghanistan Biodiversity Conservation Program continues through a biodiversity earmark. They can also direct donations directly to the Afghanistan program through the WCS website. Our current funding ends in the next year and a half, and there are many areas of Afghanistan yet to be explored, much less conserved.

FURTHER READING

- WCS: Afghanistan Biodiversity Conservation Project

- Trekking in the Wakhan Region

- On-line travel guide to Afghanistan

- Survival Guide to Kabul

Sampling Afghanistan’s wildlife

Altai weasel (Mustela altaica), Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus), Asiatic brown bear (Ursus arctos), Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra), Geoffroy’s Bat (Myotis emarginatus), Gray wolf (Canis lupus), Hare (Lepus tolai), Ibex (Capra ibex sibirica), Kashmir Cave Bat (Myotis longipes), Lesser Horshoe Bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros), Long-tailed marmot (Marmota caudata), Lynx (Lynx lynx), Marco Polo sheep (Ovis ammon polii), Markhor (Capra falconeri), Mehely’s Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus mehelyi), Mouflon (or Urial) (Ovis orientalis), Pallas’ cat (Otocolobus manul), Pikas (Ochotona sp), Red fox (Vulpes vulpes), Sind Bat (Eptesicus nasutus), Snow Leopard (Uncia uncia), Stoat (Mustela erminea), Stone marten (Martes foina), Tiger (Panthera tigris), Wild Goat (Capra aegagrus), and Zarudny’s Jird (Meriones zarudnyi)