How to save the world’s oceans from overfishing

How to save the world’s oceans from overfishing

An interview with the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Mike Sutton

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

July 9, 2007

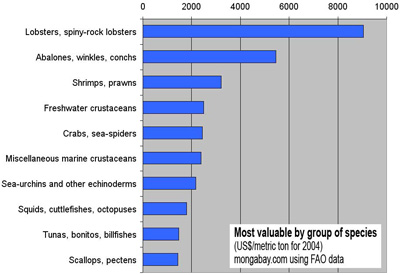

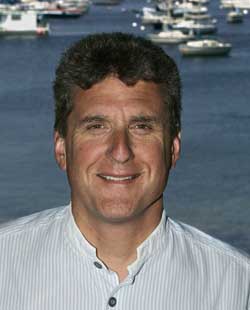

Global fishing stocks are in trouble. After expanding from 18 millions tons in 1950 to around 94 million tons in 2000, annual world fish catch has leveled off and may even be declining.

Scientists estimate that the number of large predatory fish in the oceans has fallen by 90 percent since the 1950s, while about one-quarter of the world’s fisheries are overexploited, depleted, or recovering from depletion. Unsustainable fishing practices like bottom-trawling and some forms of long-lining not only deplete targeted species, but net sea birds, turtles, and other marine life, while destroying delicate ecosystems like deep-sea reefs. About one quarter of global fish catch is tossed back overboard, dead or dying, as bycatch.

World production (million metric tons) from capture fisheries and aquaculture. Graph modified from an FAO graphic. |

Until recently few people gave much thought to ocean conservation. Despite evidence from the overexploitation of whales and North Atlantic cod, it was generally assumed that ocean species had nearly boundless capacity to recover from overfishing. Powerful lobbying by the fishing industry meant that instead of addressing the problem, governments subsidized commercial fishing to the tune of at least $15 billion — and perhaps as high as $50 billion — a year, worsening the carnage. Driven by these perverse incentives and greed, industrial fishing put the livelihood of tens of millions of subsistence fishermen at risk while threatening the primary source of protein for some 950 million people worldwide.

Despite these dire trends, the situation is changing. Today some of the world’s largest environmental groups are focused on addressing the health of marine life and oceans, while sustainable fisheries management is at the top of the agenda for intergovenmental bodies. Conservation groups are working with governments to establish marine reserves, ban destructive fishing practices, protect key species, and educate consumers, though progress is slow in the face of continued lobbying by industry. Some believe the best approach to addressing overfishing is to bring industry on board, using the argument that sustainable practices will ensure the industry survives for the next generation of fishermen.

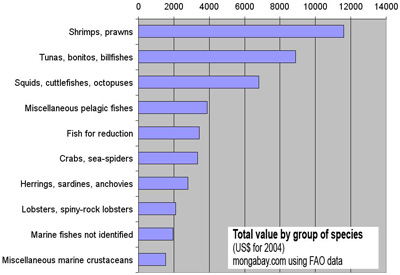

Mike Sutton |

At the forefront of these efforts is Mike Sutton, director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s conservation program: the Center for the Future of the Oceans. The aquarium, which has long been recognized as one of the world’s most important marine research facilities, is pioneering new strategies for protecting the planet’s oceans. Sutton says the approach has four parts: establishing new marine protected areas, pushing for ocean policy reform, promoting sustainable seafood, and protecting wildlife and marine ecosystems.

In June 2007, Mike answered questions on the aquarium’s role in marine conservation and his outlook for world fisheries.

INTERVIEW WITH MIKE SUTTON

Mongabay:

Some people are calling last month’s CITES meeting a failure, not recognizing that CITES focuses on trade. While trade is an issue in overfishing, doesn’t depletion occur in the absence of trade?

Sutton:

Depletion of fisheries certainly occurs in the absence of international trade, but trade often fuels additional overfishing. Carl Safina and I were behind the 1991 effort to get Atlantic bluefin tuna CITES listed, a move that would have shut down trade. Since trade was driving overfishing we figured we could stop it by shutting down international trade. If you can’t get fisheries managers to do their jobs then sometimes conservationists try to get CITES to step in to shut down the trade that is fueling the overfishing. That’s the theory at least, but it doesn’t work very well as you saw with sharks when they failed to win protection this time around. And bluefin tuna is still not listed on CITES at all, despite the fact that it qualifies hands down.

CITES has been quite reluctant to get involved in commercial fisheries especially after the 1991 memorandum of agreement with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the U.N. agency which oversees fisheries management. Basically the purpose of the memorandum was to remind CITES that FAO has jurisdiction in fisheries. A lot of it is turf wars among agencies.

Mongabay:

So has anything come of this since 1991?

Sutton:

While we’ve never been successful in winning CITES listing for species like the bluefin tuna, we’ve been able to use the prospect of a CITES listing to hold fisheries management bodies accountable. It gives them an incentive to do a better job and gives us a lever to strengthen fisheries management. In the case of bluefin tuna, ICCAT (the Atlantic Tunas Commission) took steps to improve management in the wake of our CITES petition. So the fisheries managers are doing a better job now as a result an unsuccessful CITES intervention in 1991.

Mongabay:

So you made a progress from a loss?

Sutton:

Exactly. These things don’t happen over night. It’s a matter of slow change.

Ocean conservation has always been playing catch up to land conservation. So while the world is willing to protect African elephants by banning the ivory trade which was driving poaching, we’re not there yet with commercial fish species like bluefin tuna. It’s the most valuable fish in the ocean. So, for example, even the U.S. and Canada–pretty green countries in terms of voting for African elephant conservation–won’t vote for bluefin tuna conservation since they have a strong tuna fishing lobby at home. The U.S. actually helped defeat the 1991 initiative on bluefin tuna. It’s been very difficult since.

Mongabay:

Is Bluefin tuna on IUCN’s Red List?

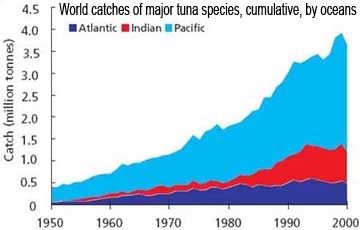

World catches of major tuna species, cumulative, by oceans, 1950-2000. Graph courtesy of FAO. |

Sutton:

WWF and the Zoological Society of London convened a workshop in London about 15 years ago to review the status of commercial fish species and see if any qualified for the IUCN Red List. As a result of this workshop, the bluefin tuna was listed as critically endangered which triggered a huge uproar among fisheries managers who said the Red List criteria were only for terrestrial animals and didn’t apply to marine species. We disagreed. Though marine species can recover after population reduction, it doesn’t mean we should take them down to less than 10 percent of their historic population size. This is what we’re seeing with the bluefin in the Atlantic and the South Pacific.

Mongabay:

Do bluefin require a certain population density for reproduction?

Sutton:

We don’t know for sure, but we worry about the “blue whale” effect where their population is brought down to a level where individuals can’t find each other to spawn and they may never recover. We’re concerned that the bluefin tuna is close to reaching some sort of threshold point, like the blue whale did, where they won’t be able to come back. Ordinarily, commercial extinction usually occurs long before biological extinction. (Commercial extinction means there are not enough animals out there to make it worth your while to go after them).

The trouble with bluefin is they are so valuable in the Japanese sashimi market that the last bluefin will be the most valuable. That means commercial and biological extinction are one and the same. We are facing the very real prospect of hunting this animal to biological extinction just as we did the passenger pigeon, the Steller’s sea cow, and other species.

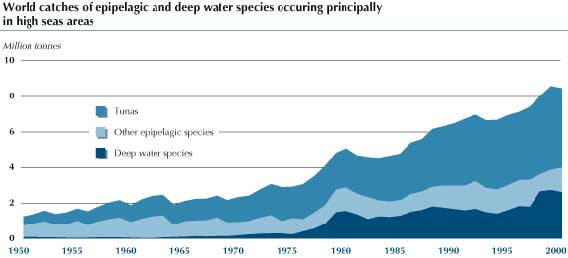

World catches of epipelagic and deep water species occuring principally in high seas areas. Graph courtesy of FAO. |

The Bluefin tuna is really the poster child of overfishing. It is the most valuable fish in the sea: one fish in the Tokyo market can bring more than $150,000. We call it the “Porsche of the Oceans” because the bluefin tuna is the size of a Porsche, 10 feet long and a 1500-pound upper size limit; it as fast as a Porsche, 0 to 60 in 5 seconds; and they are as valuable as a Porsche, 100 grand.

In Bluefin tuna, we’re seeing all the classic signs of overfishing. Today fishermen cannot even catch the quota the government gives them, which is symptomatic of a collapsing fishery, like the North Atlantic cod. The U.S. government issues the quota for U.S. waters but because this animal is highly migratory, it is managed by international treaty and the Atlantic Tunas Commission manages the Atlantic population. The quota is drawn up among fishing countries, including those that fish on the high seas like Japan. In recent years, fishermen in the United States have simply been unable to catch the quota the government grants them, which is a really bad sign if you are a fishery manager.

Let me give you a terrestrial analogy. We’ve long banned market hunting—hunting wild animals for commerce instead of subsistence–on land. Passenger pigeons and waterfowl are prime examples in the U.S. Passenger pigeons, which used to cloud the skies of the east coast, were completely exterminated by market hunting. Now we stopped the practice on land but we do it in the ocean–it’s called commercial fishing. Nothing wrong with that of course — we all love seafood — but if we’re going to market hunt in the ocean we really ought to do it on a sustainable basis.

Mongabay:

Are pirate or extraterritorial fishermen a problem?

Sutton:

They are. Illegal activities–like pirate fishing–in the ocean have always been especially problematic because it’s difficult to patrol the high seas, but the bigger problem is that what is perfectly legal has been unsustainable. It is not illegal to overfish in the United States. In fact overfishing is quite legal as long as it’s sanctioned by a management authority like fishery management bodies or regional fisheries management councils. So, yes while illegal activity will always be a problem that requires coast guard or state and federal fisheries patrols, the fundamental issue is that what is legal has just been simply unsustainable. And that situation continues today.

Mongabay:

So, that kind of begs the question, can these policy makers be convinced to make fishing more sustainable?

Sutton:

Well, that’s definitely the big question. There have been a number of approaches over the years including trying to get some of the keystone species like tuna listed on CITES. That effort drew huge attention to the problem. Conservationists have tried lawsuits as well as traditional public policy tools such as lobbying. There are a number of new approaches which are really interesting, including efforts to persuade seafood businesses to weigh on behalf of conservation. The Marine Stewardship Council’s independent certification and ecolabeling program is one example, as is our Seafood Watch program here at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

I’m on the board of Ocean Champions which is the first political action committee for ocean conservation. Were building Ocean Champions in the Congress to bring lawmakers on board and give ocean conservation a strong voice on Capitol Hill. Ocean conservation is finally coming into it’s own after many years of taking the back seat to land conservation.

Mongabay:

Have you had much luck bringing on industry? It seems like it is in their long term interest to make the industry sustainable.

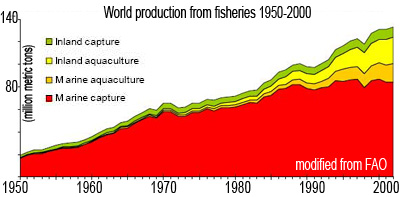

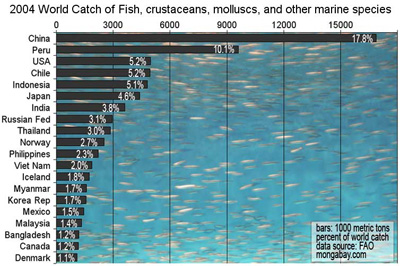

2004 global catch of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and other marine species, based on FAO data. Chart by R. Butler. |

Sutton:

Well, you would think so. I think individually that is probably true. The trouble is that the ocean has always been an open access resource. The mentality is, “If I don’t get it, somebody else will.” So, it causes a race for the fish and what happens ultimately is you have a situation like what we have on the California coast: too many boats chasing too many fish. Sure you get big catches for a few years like we saw with sardines and rockfish, but then the populations’ crash and the fishing communities crash along with them. You get these boom and bust cycles like we saw with the sardine industry many years ago. The history of fishery management is summed up in two words; serial depletion. That’s what we’ve done.

We’ve had the science but not the political will to restrain the commercial fishing industry so that it can be sustainable. We have been very successful in de-populating the ocean, but not managing it sustainably.

Now we are seeing Marine Reserves being established to put some areas off-limits to fishing so that fish have a chance to recover and spawn. We know the ocean is productive and ocean animals tend to be fecund so the ocean certainly has the ability to bounce back if we are smart enough to leave it alone. That’s the challenge. It’s a lot easier said than done.

Mongabay:

So you are seeing support from fishery managers and politicians for marine reserves?

Sutton:

To some extent, yes. The widespread failure of fishery management has led many people to look for alternative approaches that might be more successful. CITES is a good example. We’re finally seeing more and more attention paid to the ocean in general by CITES, management bodies, and conservation organizations. Fifteen years ago conservation organizations paid no attention to fishery management. Now there is not a fishery management council that can sneeze without somebody taking notice. That is real progress. There’s more transparency in the process, which is encouraging.

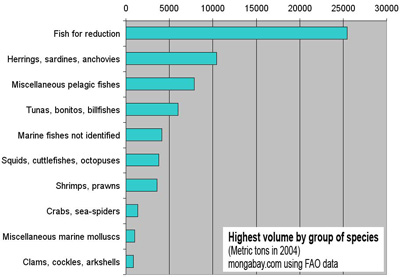

2004 global seafood catch by group of species, ranked by volume, based on FAO data. Chart by R. Butler. [click image to enlarge] |

Nevertheless marine conservation is well behind land conservation. For example, about 10% of the land surface in the United States is protected in one way or another through national parks, national forests, state parks, and wildlife management areas, while less than 1% of the ocean has similar protection. It’s an uphill battle because there are so many fishing jobs and a strong industry lobby. Elephant poaching is easy to fight because there is no industry lobby.

Commercial fishing is much more difficult to address because there is a huge industry lobby–it’s only slightly less powerful than the forest products lobby. Fishermen tend to want to fight regulation because they see it as limiting their livelihood. Actually what it’s trying to do is preserve their livelihood but nobody understands that when their home and boat mortgages are tied together and they need to have fish on the dock today. If they default on their boat mortgage, they may lose their home. So there are good reasons why overfishing is so difficult to control.

Mongabay:

Would eliminating subsidies make a big difference? Would some fishing become uneconomic without government assistance?

Sutton:

Oh, yes. When I was at WWF we spent a lot of time and energy working on fisheries subsidies because in many respects subsidies are why we have too many boats chasing fish. The acquisition of the boats and equipment is subsidized. There is a diesel fuel tax rebate and all kinds of subsidies for commercial fishing, especially in Asia. The U.S. has done away with most of them, but around the world fishing subsidies are huge–second only to agriculture and possibly mining in terms of perverse subsidies. In this case, subsidies are the root cause of overcapitalization, which is one of the biggest drivers of overfishing.

Mongabay:

Is Ocean Champions focused primarily on U.S. politicians or are you also looking at foreign lawmakers as well?

Sutton:

Ocean Champions works specifically with the U.S. Congress. We’ve only done a little bit of work at the state level with the up-and-coming politicians. The need for the program is clear–the conservation community has spent a couple decades getting beaten by the likes of politicians like Sen. Ted Stevens from Alaska who is acting on behalf of his fishing industry. These guys resent conservation and defeat it by modifying federal laws that govern fishing.

We finally decided to do something about it. Ocean Champions is our way to cultivate champions for the oceans among members of Congress. This is not easy to do. It’s not like finding support for elephant conservation. Since there are no elephants in the US except in zoos, politicians are happy to support elephant protection efforts. But lots of members of Congress have fishing communities in their districts, making it difficult for them to support marine conservation.

You see odd circumstances like Barney Frank and Gerry Studds—Studds was a former Congressman from Massachusetts while Barney Frank is the current Congressman for that area. They couldn’t be greener or more liberal except for one thing: they defend to the death their fishing industries and work to defeat conservation measures in the ocean. They are happy to vote for elephant conservation measures, but not conservation measures that they perceive as a threat to their communities.

So the politics of fishing are very difficult and I believe this is the main reason why fisheries management hasn’t worked very well. We’ve really been let down by public policy. We wouldn’t need organizations like the Marine Stewardship Council and Ocean Champions if legality would guarantee us sustainability, but does not. Overfishing is quite legal in the U.S. That just has to change.

Mongabay:

So, is the idea then to have the United States lead by example? If we have sound sustainable policy, then in theory that would influence policy in other places?

Sutton:

I think that is part of it, yes. The US has always prided itself as a leader in conservation and science. We’ve believe that if it’s done right here other places will want to emulate us as they have our national park system. I think that’s by in large been the case. Take California for example. In the last couple of years, we’ve seen a lot of progress in ocean conservation. The Governor [Arnold Schwarzenegger] turned out to be a great champion of the ocean. He has signed legislation and appointed key people to various state bodies. He is really batting almost a thousand on ocean issues and wants to leave an ocean legacy. As a result, California has done far more than the federal government in the last few years for oceans, and California is also a good model for the other states. When the Governor of Oregon saw what Governor Schwarzenegger was doing here, he wrote a letter to his ocean policy advisory council and said, “I want to do the same thing. I want to set up a series of protected areas along my coast.” So, it may be an old cliché that California leads the nation, but it’s certainly the case with respect to the oceans.

Mongabay:

What’s the best way to extend this to other countries, specifically looking at nations that have an interest in expanding their commercial whaling?

Sutton:

Well, whaling is an interesting example. I spent a number of years on the U.S. delegation to the whaling commission. First of all, it’s important to recognize that the issue is not sustainable use of wildlife. That is the issue with fisheries. That’s the way Japan, Norway, Iceland look at whales — just like it is another fishery and it doesn’t matter that whales are marine mammals. But for most of the rest of the world, it’s not about whether we can use whales sustainably, it’s about protecting them outright. You can see this difference in the way we treat marine mammals here and the way we treat the fisheries. With fisheries, the objective is not to protect them. The objective is to use them sustainably. But our objective with marine mammals is to protect them and achieve mortality close to zero. That is the goal of the Marine Mammal Protection Act here in the United States. So, with whales it’s really a matter of international democracy. As long as the non-whaling and anti-whaling countries outnumber the whaling nations, you won’t have commercial whaling. If Japan is successful in recruiting other countries to vote its way, then you will have a limited resumption of commercial whaling. It’s as simple as that.

A majority of the world’s population does not want to kill whales. They want to enjoy them while they are alive. Toady, whale watching is a huge industry all over the world. Right here in Monterey, a lot of our former commercial fishermen are now whale-watching captains.

Mongabay:

What is to stop Japan from raising the “scientific whaling” quota every year?

Sutton:

Well, they are members of the International Whaling Commission (IWC), a treaty body that regulates commercial whaling and has included a moratorium on commercial whaling since the mid-eighties. The only way to legally kill whales now is either through a loophole in the treaty that allows scientific whaling or research whaling or by taking what is called an exception to the moratorium on commercial whaling. So, Norway and Iceland both have filed exceptions to the moratorium. They are commercial whaling today on a very limited basis. Nobody is whaling in the Antarctic like the old days except Japan, which is taking a few whales in the Antarctic each year under the guise of scientific whaling. They are using that loophole in the treaty to just keep the industry alive. But for the rest of the world, whaling is an anachronism. It’s a piece of history that is rapidly disappearing. Most countries don’t want to do it anymore.

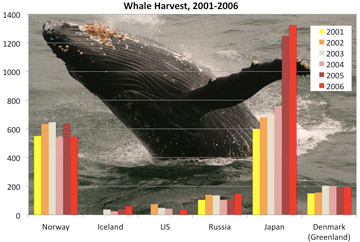

Annual whale harvest from 2001-2006 (2006 figures are not complete). Graph by mongabay.com, data from Science, background image courtesy of R. Wicklund OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP); University of North Carolina at Wilmington |

The United States had whaling shore stations until 1970 right here on the California coast. A lot of people don’t remember that, but it’s true. We haven’t killed whales commercially for the last forty years and there is no chance the United States going back to whaling unless it’s for aboriginal subsistence. A few native American tribes take whales around the country but they only take a few each year, usually gray whales which are quite abundant in that part of the Pacific. While that’s a controversial issue, nobody is arguing that the gray whale is in trouble. The Makah in Washington are simply exercising their historic rights to aboriginal subsistence.

What’s the best way to get Japan, Norway, and Iceland to stop? That’s a good question. Conservationists have tried consumer boycotts. These countries have always been outvoted the whaling commission, but they’ve been trying to build support to overturn the moratorium on whaling. The Japanese have been successful on recruiting a number of countries to their side.

Mongabay:

In land-locked countries, right?

Sutton:

Yes, right. It’s what we used to call yen diplomacy. The Japanese offer development assistance to poor countries in return for their votes at the IWC. Of course, we’ve done the same thing on other issues. Nations use financial assistance as a political tool all the time.

Mongabay:

But in general you’d say that whaling is pretty much done? It’s not going to come back in any meaningful form in the immediate future?

Sutton:

I think that’s right. I don’t think we’ll ever see thousands of humpbacks, fin, and blue whales being killed like we saw in the 20th century. For one thing many species of whales remain depleted: their populations haven’t recovered to pre-whaling levels and they may never recover. There are still a few blue whales around. We see them occasionally off the coast here in Monterey, but many fewer than used to be in the ocean. I’ve been to the Antarctic three times and in some places it’s like you are walking through the killing fields. There are so many whale bones from the old 19th century whaling operations. I don’t think we will ever go back to that. I think we’ve learned our lesson. Commercial whaling is a particularly bad chapter in our history of ocean exploitation. Of course there is a parallel in what we were doing with fisheries like bluefin tuna today. There are something like fifteen species of great whales and whalers were down to the eleventh largest species of the great whales when whaling was finally stopped. Whalers went from one to the next to the next to the next. They took the biggest ones first, the blue whale, the fin whale, the sperm whale and they worked their way down to the smaller whales like the right whale and the humpback and so forth. When they finally stopped they were killing the Minke whale, which is much smaller than the largest species. We were basically doing the same thing with fisheries today; serial depletion—overfishing one species after another until they’re gone.

Mongabay:

They want to argue that, at least today, that fisheries are much more important than whales in terms of subsistence, right? Industries are built around fisheries and people eat fish.

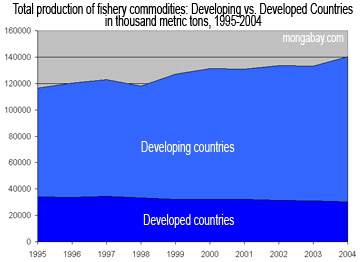

Total production of fishery commodities from 1995-2004: developing versus developed countries |

Sutton:

Well, yes. There were industries built around whaling in the 19th century, fisheries have always been more important than whaling in terms of a food source. To me that is all the more reason to get management right. The United Nations tells us that if we could manage fisheries better on a global basis, we could take more from the oceans–a lot more than we do today. We’re talking 10 to 20 million metric tons of seafood more each year if we managed fisheries better globally. It’s because we’re not managing fisheries very well that we see all this depletion and closures of fisheries. It means less and less seafood for us. The only way we are making up the difference is through imports and aquaculture (fish farming). That carries its own set of environmental downsides.

Mongabay:

You mention aquaculture. What should a responsible consumer choose between farmed and wild caught salmon?

Sutton:

No doubt wild caught salmon is a far better choice today. Farmed salmon has a number of problems including health concerns and environmental concerns. Farmed salmon is less expensive, much more readily available, and makes up a much larger proportion of salmon on the marketplace today in this country that does wild salmon, but for your own health and for the health of the environment, there is not much doubt that wild salmon is a better choice. The wild salmon fisheries in Alaska were certified by the Marine Council seven years ago as sustainable and well managed. It tastes better, it’s better for you, and it’s better for the environment. So, wild salmon is a pretty hands down choice at this point.

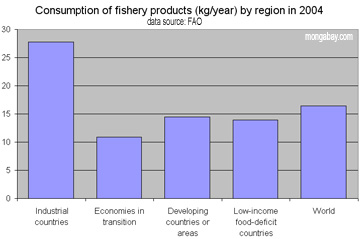

Per capita consumption of fishery products by region. |

The challenge of course is not to do away with the salmon farming industry, it’s to green it. We need a Blue Revolution. You remember the Green Revolution? It industrialized agriculture around the world. Well, a green revolution fed a lot of people, but it also had enormous environmental and social downsides. What we need to do is figure out the Blue Revolution. It’s about figuring out how to farm fish, like salmon, in an environmentally friendly manner. We haven’t done that yet, but we are working on it.

Mongabay:

What about the open water aquaculture they are doing off Hawaii?

| The importance of fisheries to the developing economies

The relative importance of trade in fishery products in 2004 for net exporters of such products: fishery exports as a percentage of agricultural exports.

|

Sutton:

This is a big issue right now. Congress has just introduced a bill on behalf of the Bush administration to create and subsidize a new offshore aquaculture industry. There are only a few examples of this right now, such as Kona Blue off Hawaii and the experimental tuna aquaculture that the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute is doing in Southern California.

There is no doubt aquaculture has real promise. Today, fish farming is the fastest growing sector of the global food supply. It’s a mega trend–it’s not going away no matter what we do. So, today our challenge is to green it.

The problem with the government’s bill right now is that it doesn’t contain environmental safeguards. It orders the government to prepare those down the line. That’s not good enough. We’ve got to write tough environmental standards into the bill. Thankfully, the Chairman of the Senate Congress Committee said, “I’m introducing this bill at the request of the White House, but I think it needs work. One of the things we need to do is put environmental safeguards in it.”

Mongabay:

What are the big environmental issues involved with offshore aquaculture? Is it antibiotic use, pollution, or escaped fish?

Sutton:

There are a number of issues involved. Certainly pollution–effluent from the pens–is one. Basically you are talking about huge feedlots in the ocean. As we know from land, feedlots have huge pollution problems. Just look at cattle lots, pig farms, and chicken farms. The state of Oklahoma is suing the adjacent state of Arkansas for the effluent from chicken farms polluting streams that flow across the state border. In the ocean of course you have a lot of volume for dilution but that doesn’t mean we should tolerate high levels of pollution.

Mongabay:

What about antibiotics? With a high density of fish is there heavy use of antibiotics? Is there a risk that these with leak out into the ocean environment and cause other problems?

Sutton:

That’s right. Farmed fish are often treated with antibiotics and pesticides that end up polluting the ocean. Farmed fish are also sometimes fed contaminated feed which causes the fish themselves to become contaminated. So, there are a lot of issues with offshore aquaculture and nearshore aquaculture that we need to work out.

There is also introduction of exotic species. For example most of the salmon farmed in the United States and Canada is Atlantic salmon. It’s farmed on the West Coast where it doesn’t belong. It’s like Jurassic Fish. If too many of them get out, you could have introductions of exotic species which would then compete with native species. That is what is happening in the Pacific Northwest now. You’ve also got parasites like sea lice that infect the fish farms and then wild salmon populations.

Mongabay:

Going back to the consumer’s role, I know that the aquarium has had a major impact with its Seafood Watch guides–can you tell us a little more about these efforts?

The Seafood Watch Program |

Sutton:

Well, the whole idea is to create powerful economic incentives for sustainable fishing and ultimately conservation of the ocean. The Seafood Watch program, which is about seven years old now, was originally intended to build and maintain the salience of this issue with consumers, chefs, and businesses. The idea is that if consumers and businesses give preference to sustainable fisheries, they send a powerful signal from the marketplace back into the industry that there is a reward for improving fishing practices.

What we really want to do at the end of the day is change the politics of fishing by swinging industry support behind more effective regulation. In the past industry has been at best a benign force, while at worst it has actively lobbied against conservation measures. We want to turn that on its head. The ultimate goal of Seafood Watch is to change the politics of fishing.

What we’ve succeeded in doing so far after seven years and 20 million Seafood Watch cards is build the salience of this issue dramatically. The seafood cards are the most popular things we have ever done for aquarium visitors. Recent evaluations have shown that they make a huge difference in terms of awareness and behavior change among consumers, but more importantly we’ve also won the attention of the biggest seafood buyers in the nation; Wal-Mart, Costco, Aramark. Food service, retailers, and distributors like Sysco. Many of the nation’s biggest seafood buyers are now making commitments to sustainable seafood. So, it’s rapidly becoming the commercial norm for big seafood buyers to pledge to buy only seafood from sustainable sources. Now, it’s the same problem that Michael Pollan identified in his book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma. He talked about the growth of industrial organic. When Wal-Mart goes organic, can the organic industry scale up to supply Wal-Mart, the biggest food retailer in the United States, or do you lose the essence of the movement in so doing? The jury is still out on that, and whether sustainable seafood can supply the biggest buyers in the nation. But what we have achieved so far is the biggest retailer and biggest food service company in the United States have made commitments for sustainable seafood and that is huge because if it is not on a shelf or not on the menu, you and I can’t order it. These businesses make the choices on our behalf.

Visitors admiring the kelp forest tank at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Photo by R. Butler. |

Before long, we hope unsustainable seafood simply won’t be available to consumers which will be a good thing.

It’s important to recognize that the seafood movement has never been entirely or even mainly consumer-driven. However, consumers have an important role to play especially in maintaining the salience of the issue. If you look at the principles of social marketing, consumer salience is important because it gets you the attention of the big buyers. What you really want is the big seafood buyers to change. If they don’t buy the wrong kind of seafood, then the consumer can’t either. We recognize this. It would take far too long, if it were possible at all, to get the attention of the big seafood buyers through consumers alone. If you talk to McDonald’s about why they are putting pressure on chicken producers to give chickens a better life, it’s not because consumers are complaining. It’s because PETA conducted a sophisticated campaign to get McDonald’s to do that.

Mongabay:

That is interesting. The approach ties in to what an innovative group is doing in the Amazon with certification of agricultural products. Educating every one of those consumers would be quite costly and time-consuming. So, it also eliminates the dilemma of me, as a consumer, going to the grocery store and trying to figure out what fish is OK to buy if the only fish available is certified.

Sutton:

Exactly. That is the idea. The same thing is true of the Forest Stewardship Council in the forest products sector. The idea there is if Home Depot stocks only wood from sustainable forest operations, then you don’t need to worry about every consumer and every shopper at Home Depot being informed because the only choice on the market is a sustainable choice. The same thing has happened with dolphins and tuna. Right now you can’t buy dolphin-unsafe tuna on the U.S. market. It’s all dolphin-safe for two reasons. One is that it’s become the commercial norm. Nobody wants to sell dolphin-unsafe tuna anymore and it’s illegal to do so. That is the second reason. The government passed legislation saying that all imports of tuna in the United States must be dolphin-safe. They took that action after the industry changed its practice.

Mongabay:

Beyond the Seafood Watch program, how else is the aquarium involved in conservation efforts?

Sutton:

My program is the conservation arm of the aquarium–a program that’s a bit unusual for an aquarium. Aquariums have been involved in field conservation work for many years but conservation advocacy is a little different. We have scientists on our on staff, but we go beyond field research and field conservation work into policy advocacy. Most aquariums are much more comfortable with awareness building and education than they are ocean advocacy. That is understandable and is not necessarily problematic. In our case, after 20 years our board at the Monterey Bay Aquarium decided that it was time to take the gloves off and get more directly involved in ocean conservation. So, Julie Packard asked me to come on board and launch this program.

Big Sur on the California coast south of Monterey. Photo by Nancy Butler |

We have four goals. One is transforming the seafood market so that it favors conservation. We talked about that.

Another goal is to create marine protected areas off the United States west coast, particularly California. Right now that is primarily a state process—hence I spend more time in Sacramento than I do in Washington, D.C.

A third approach is improving ocean governance. Four of our aquarium trustees served on the Pew Oceans Commission, a group of distinguished Americans the Pew Charitable Trust asked several years ago to help figure out how to improve the management of U.S. oceans. So, we’re following up on on the report and recommendations of that commission as well as the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy to see if we can help the government–state and federal–do a better job of managing our oceans. So, for example, last year we helped to negotiate and broker what became the West Coast Governors’ Agreement on Ocean Health among the governors of Oregon, Washington, and California. They share the California current ecosystems so why not share their expertise in ocean management?

The fourth area we’re involved in is saving the key species and their habitats on the California coast. These are animals that people fall in love with when they visit the aquarium: seabirds, sea otters, sharks, sea turtles and so forth. These are our keystone species on the coast that need our conservation support.

Mongabay:

Are there any captive breeding programs for endangered marine species or are marine reserves more of a priority?

Leopard shark at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Photo by R. Butler. |

Sutton:

While in situ ocean conservation through marine reserves is vital, captive breeding programs are important, too. In fact, this is something that a few of the aquariums have been involved in for years. The IUCN runs a program called the Species Survival Network which is a huge database for keeping track of genetic material that we have in captivity for endangered species, both marine and terrestrial. So, we participate with the species survival plans for a number of endangered species. We’ve even learned to breed jellyfish in captivity. Our staff are real pioneers in terms of captive breeding. We breed most of the exhibit animals in captivity or if we take them from the ocean, we release them when we are finished. The most prominent example of that is we’ve had two juvenile white sharks on display. Both of them were successfully released back into the wild right here in Monterey Bay. We put satellite tags on them so we could find out what happened to them. They went offshore for a while and came back in and started feeding and everything went well.

The white sharks were a big attraction for the aquarium. They allowed us to serve hundreds of thousands more people than would otherwise have come here. The first white shark in 2004 brought two or three hundred thousand more people to the aquarium. People have a morbid curiosity about big predators like sharks. Charismatic animals are an important piece of what we do. They help us attract visitors who are then exposed to our conservation messages.

Mongabay:

What’s your big picture outlook for world fisheries? Are you optimistic that we’ll become sustainable before it is too late?

Sutton:

I am optimistic. I think the productivity of the ocean and the fact that there are still pristine marine areas means that we have time to bring some of these species and ecosystems back. We are also are seeing a big trend towards ecosystem-based management of the ocean instead of just single species or single sectors like fisheries. We are beginning to recognize the importance of managing the entire ecosystem and that’s a good sign. Whether we’ll actually get there in time to make a difference, I don’t know.

Jellyfish at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Photo by R. Butler |

It is promising to me that this is beginning to happen, so I am very encouraged. I am very hopeful that we will catch this in time to do something about it, and that we will have the collective restraint to allow the oceans to recover. It is just like on land. It isn’t just about managing these areas so catches are sustainable, for example. It’s a matter of restoration. Will we have the fortitude to leave these areas alone, close fisheries when necessary, and restore them well enough so that we can go back to catching more fish on a sustainable basis? I hope so.

Mongabay:

What can the average person at home do to help the situation?

Sutton:

People like actions they can take in their own lives to help. Recycling and the Seafood Watch pocket guides are both far more popular among our aquarium visitors than joining environmental groups or writing politicians. We recently worked with Warner Brothers Home Entertainment to put the Seafood Watch card in all 9.5 million DVD’s of the movie Happy Feet, the animated penguin film. That virtually doubled the reach of the Seafood Watch card overnight. So, we are going to continue to get the word out there to people what they can do to help. It really is just making better choices on behalf of the ocean.

Mongabay:

Do you have advice for students interested in pursuing careers in marine biology or marine conservation?

Sutton:

Well first of all it’s very important to have a good grounding in science. So a master’s degree in marine biology is always a good thing to have.

Sea anemone at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Photo by R. Butler. |

If you want to get more into the politics of the issues then degrees in marine resource management and marine affairs will help. The conservation community has always hired a lot of lawyers and scientists, but we have recently started hiring business people as well–people with MBAs who have an understanding of how industry and business works, so that we can influence what they do as well. In the early days of the environmental movement business was the enemy. Business was the opposition. Nowadays, that is no longer true. We find business partnerships and collaborations are more and more important. I am encouraged by that. I think that means that we will be able to harness the power of commerce itself to save the oceans. If you believe people like Paul Hawken, the author of The Ecology of Commerce, then the only force powerful enough to reverse the unsustainable use of natural resources is commerce itself. That is what our seafood work is really all about, harnessing the power of commerce itself in favor of conservation, not as a substitute for enlightened management of the ocean but as an incentive to accomplish it.

Mongabay:

Why did you get involved with marine conservation?

Sutton:

You mean why did I forgo working as an attorney for a law firm and making ten times as much money?!

Mongabay:

Exactly.

Sutton:

Good question. I ask myself that a lot, but the truth is my career has always been in conservation. I got involved in ocean conservation because I did my graduate work on the Great Barrier Reef. The scenery, the beauty of the oceans, the marine biodiversity up close and personal, and I realized that while there was a lot of science going on in the oceans, there was very little conservation work underway aimed at protecting the oceans. We really needed conservation professionals to focus on the oceans. That’s why I worked to start the marine conservation program at WWF, then went on to work at the Packard Foundation, the largest private funder of ocean conservation in North America, and finally came to start this conservation program at the aquarium. I believe we really do need to level the playing field with the land. We need to protect our oceans as well as we protect our land. We are just now starting to see some parity there, but it’s been long in coming. Decision makers, politicians, conservation groups, and is the public are paying attention now. That’s the good news for the future of our oceans.