Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

An interview with Dr. Daniel Nepstad:

Amazon rainforest at a tipping point

But globalization could help save it

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

June 4, 2007

The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes.

Despite its scale — the basin covers 40 percent of South America — the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belém, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development.

Daniel Nepstad in Brazil |

Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.

Positive signs

Nepstad notes that since the beginning of 2004, Brazil has created more than 20 million hectares of protected areas in the Amazon region. If effectively enforced, his group estimates, this action will prevent one billion tons of carbon from being transferred to the atmosphere through deforestation by the year 2015. With the economic damage of carbon emissions presently estimated at $75-$150 a ton, Brazil’s measures could be worth more than $100 billion. And while it will put out tens of millions in direct payments and forgo tens of millions more in lost opportunity costs, Brazil will see nothing from the international community for its efforts. It may get polite thank-yous from foreign diplomats and perhaps some press in National Geographic, but it will see no financial rewards for its substantial emissions savings.

But this could soon change. Under a widely supported international initiative, Brazil and other tropical forest countries may see compensation for measures to reduce deforestation that would otherwise occur. While Brazil has moved slowly on the concept, there is a real possibility that industrialized countries will support what has been termed the “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation” (RED) initiative.

|

Nepstad believes that if adopted, RED could trigger the largest flow of money into tropical forest conservation that the world has ever seen. Besides climate benefits, the plan would help maintain critical ecosystem services while safeguarding biological diversity.

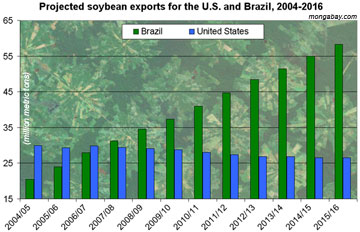

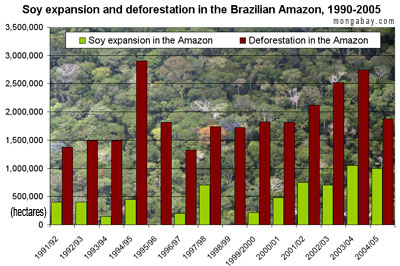

Beyond the RED plan, Nepstad sees other encouraging trends in the Amazon. Since 2004, deforestation rates in Brazil have dropped by more half due to government intervention — including crackdowns on illegal forest clearing and establishment of protected areas — and economic trends, including fluctuations in currencies and commodity prices. Globalization, surprisingly, may also be fueling a dramatic shift in sentiment among large-scale forest developers, he says.

Nepstad suggests that globalization — the economic force long demonized by some environmentalists — may be fostering new priorities among producers of agricultural commodities in the Amazon. In a 2006 paper published in Conservation Biology, Nepstad and his colleagues argued that the Amazon beef and soybean industries, the primary drivers of Amazon deforestation, “are increasingly responsive to economic signals emanating from around the world.” This development, they say,

-

“increases the potential for large-scale conservation in the region as markets and finance institutions demand better environmental and social performance of beef and soy producers. Cattle ranchers and soy farmers, who have generally opposed ambitious government regulations that require forest reserves on private property, are realizing that good land stewardship — including compliance with legislation — may increase their access to expanding domestic and international markets and to credit, and lower the risk of losing their land to agrarian reform.”

But problems remain

Hot Pixels, in red, show where fire activity was greatest in 2004. “Tanguro” is Fazenda Tanguro, a private soy farm in Mato Grosso state, where Nepstad and colleagues conducted burning experiments to study how rainforest responds to fire. Image courtesy of the Woods Hole Research Institute. |

While these developments are hopeful, Nepstad warns that the Amazon is not out of danger yet, with surging demand for biofuels and climate change on the horizon. Nepstad is especially concerned about the “positive feedback” loops between Amazon forest fires and drought; climate change and increased deforestation will only worsen the multiplier effect of these threats. The worst outcome: With increased deforestation and higher temperatures interacting with an extended version of the 2005 Amazon drought, Nepstad says, as much as half the Amazon rainforest could be gone by 2030, replaced by fire-prone scrub vegetation. The loss could release more than 50 billion tons of carbon to the atmosphere, further worsening climate change and drying the basin well before any of the major biome shifts projected by global-warming models.

Mongabay: You were co-author on a Science policy paper published last week that recomended avoided reforestation as a strategy for fighting climate change. Are you seeing momentum in support of the concept?

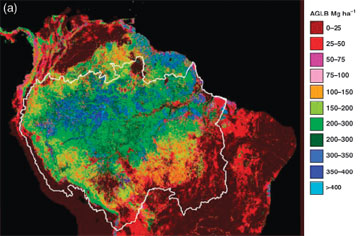

Aboveground live biomass (i.e. carbon storage) in the Amazon region. Image courtesy of Sassan Saatchi et al (2007). Click to enlarge. |

Nepstad: The “reducing emissions from deforestation” (RED) initiative has been probably the hottest thing going at climate negotiations the last few months. There’s a strange alliance of coalitions. For example, small countries like Panama fear that there might not be enough carbon credits to go around if countries actually succeed in lowering deforestation. This concern is very substantial. Then there are countries like Brazil which pretty much feels that it can do whatever it wants because of its size. Brazil is maneuvering to enhance its position, particularly against the United States, India, and China. All this makes for a fascinating negotiating process.

There’s a lot at stake. We’re talking about what could become the biggest flow of funds ever into tropical forest conservation with all kinds of potential win-wins for improving rural livelihoods and protecting biodiversity.

Mongabay: In terms of the numbers, are we talking billions of dollars per year?

Nepstad: That’s what would be needed if we are to reach most tropical countries. It is important to remember that there is still a big gap between what the carbon market is paying for a ton of carbon ($10 to $20) and the economic damages to the world economy that are associated with the release of a ton of carbon to the atmosphere (estimated at about $50 – $120 per ton. Meanwhile the number we’re coming up with for the Amazon is something closer to about $5 to prevent a ton of carbon to achieve something like a 70 percent reduction in emissions. It’s amazing how cheap it could be to fight climate change by reducing deforestation.

There’s a striking disconnect between the world’s biggest environmental issue, global warming, and this very low-hanging fruit that could also has a set of very large side benefits. A big question is whether we can navigate the pitfalls that derailed negotiations during the Kyoto round.

Mongabay: Given the large delta between the cost of carbon emissions to the global economy and the price of lowering carbon emissions through reduced deforestation it seems that economics alone would drive the initiative. What’s holding it back?

Fires cause leaf shedding and open the forest canopy, increasing the risk of future burns. Courtesy of WHRC |

Nepstad: The carbon market is, of course, a function of the regulatory environment, but the regulations are simply not there. We are in the early stages of re-organizing the world economy so that it emits only a tenth of its greenhouse gases. It now appears that compensated reduction of deforestation will be added to the international regulatory framework. When we first proposed this concept in our 2005 article and at the 2003 Milan Conference of the Parties (of the UN Framework convention on climate change), it seemed like a remote possibility. Since then, a number of factors have made it much more palatable. I think the most significant one is the general public’s increasing concern about global warming as a serious threat. Now world governments are scrambling for solutions–it’s no longer just lip service. This is quite a shift from the very meek goals set forth in Kyoto.

Mongabay:

Do you see carbon finance as one of the best ways to preserve rainforests like the Amazon?

Nepstad: Yes. One interesting lesson from all this is we’ve never been very good at putting a price tag on how much biodiversity is worth to the world. Frankly, while I think it’s a beautiful concept, it does sort of miss the important functional aspects of tropical ecosystems in maintaining climate both regionally and globally, in providing clean water, in protecting soils. Now it appears that biodiversity, clean water, and healthy soils may all hitch a ride on the back of the carbon that it stored in tree trunks and branches.

Mongabay: So carbon finance is one strategy for funding rainforest conservation, what about protected areas? Last year you led a study that found parks and indigenous reserves in the Amazon help slow deforestation. Do you still see this as an effective way to conserve the Amazon?

Indigenous reserves and populations in the Legal Amazon. Maps courtesy of IBGE |

Nepstad: Yes definitely. I think this will fit with these integrated approaches that are now going to have to be developed by every tropical nation that wants to tap into this money. Our finding that these parks are not just paper parks and that they in fact have some significance in slowing deforestation-dependent agricultural expansion and fires is encouraging. But our conclusion that indigenous lands are certainly no worse, and perhaps even more important than parks because they tend to arise on the active frontier, has underappreciated conservation implications. Now the question becomes, “How can we improve the traditional livelihoods of these people so that they will continue to provide this service?” They will need health, education, and economic alternatives–the carbon initiatives have the potential to fund these sorts of programs.

Mongabay: You’ve worked in the Amazon a long time. Have you seen any shift in sentiment with regard to Amazon forest conservation?

Nepstad: There’s certainly been a shift with Marina Silva at the helm as Brazil’s Minister of the Environment. This is a woman who was a rural leader along side Chico Mendes, the famous champion of rights for Brazilian rubber tappers, before becoming a senator for the state of Acre, then elected minister of the environment. Silva has been very supportive of large-scale conservation in the Amazon and is a big reason why more than 20 million hectares of forest have been set aside in some form of reserve since the beginning of 2004.

Mosaic of forest and agriculture. Courtesy of WHRC |

Few people realize the impact of these efforts. In a 2006 paper we examined the long-term carbon effects of the creation of this mosaic of protected areas, many of which are in the hotly disputed eastern edge of the Amazon and places near the Trans-Amazon highway and the newly emerging economic corridor along the BR-163 highway. We found that these parks are going to prevent about a billion tons of carbon from going into the atmosphere over the next 8 years. While it’s going to cost tens of millions of dollars per year to implement this expanded network and will have a very substantial opportunity cost, there is currently no mechanism for rewarding Brazil for this enormous savings of something like $100 billion in avoided damages to the global economy.

Thanks to Marina, and perhaps despite her boss President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, we’ve seen an aggressive approach to conservation, to the extent where a couple thousand troops were sent into the heart of the Amazon following the assassination of Dorothy Stang, the American nun.

I’ve been in the Amazon 23 years and even 10 years ago I could have never imagined what we’re seeing today.

Mongabay: Last year Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva announced a plan to allow sustainable logging across 3 percent of the amazon rain forest. What are your thoughts on this plan?

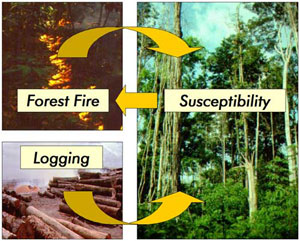

Positive feedback cycle between forest understory fire, selective logging, and forest flammability. Both understory fire and logging open the canopy, kill trees, and increase the fuel load on the forest floor, increasing forest vulnerability to fire. Courtesy of WHRC |

Nepstad: Sustainable logging is a crucial economic activity for the amazon because when it is done right it preserves the forest (and most of its carbon stocks) while providing jobs and income. I am generally supportive of the creation of public forests and the new Brazilian forest service. But I am worried about the new policy’s dependence upon government-administered timber concessions, which have not worked very well in the vast majority of tropical nations. The policy is just getting underway but our models show there is not going to be nearly enough timber coming off the new national forests to supply the timber industry. Most timber will continue to be supplied from private forestlands in deals cut between logging companies and communities, or loggers and ranchers. There are some remarkable industry-community partnerships that need to be supported and expanded through forest policy.

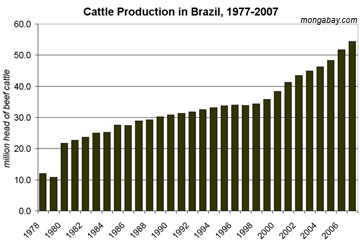

Mongabay: What about development for soy and cattle pasture? Do you see these continuing to be major drivers of forest coversion going forward?

Soy cultivation in Mato Grosso with forest remnant in background. Courtesy of WHRC |

Nepstad: We just published a paper on this. The title, “Globalization of the Amazon Soy and Beef Industries: Opportunities for Conservation“, drew some attention in the conservation community, because of the last three words.

One very recent development is that commodity markets are demanding greater legality and greater stewardship for the entire production chain. Much of that burden falls on the shoulders of producers. Examples of this are the amazon soy moratorium issued in July of last year. The moratorium was initiated by Greenpeace but basically the vegetable oils industry stepped in and took ownership of the moratorium. The Brazilian vegetable oil industry (ABIOVE) and other industries that have joined the moratorium buy most of the Amazon soy production and will now spend two years without buying any soy from recently cleared Amazon forest lands. Now there’s a very interesting process of working out how this is going to move forward, with Greenpeace, WWF, IPAM, and several other NGOs helping these big industries figure out how to identify the sources of the soy they are buying.

|

We (IPAM) have a 17-person research team based in Matto Grosso right in the eye of the hurricane for the explosion of agri-industry in the Amazon. In fact, this is why we are there. We’re trying to figure out how cattle ranchers and soy farmers can take care of their land and forests better, but still make a profit as producers. The landholders that we are working with are wondering how they can comply with the law in a cheaper way. It’s a fascinating process in which we have private land holders signing up to join the “registry of socioenvironmental responsibility” (Cadastro de compromisso socioambiental) that we created together with the “Alianca da Terra“, an NGO of ranchers and soy farmers, led by a visionary land steward and rancher, John Carter. Ranchers and soy farmers are seeing the writing on the wall. If they want to sell into the growing international markets for their products, they need to obey the law and adopt sound land stewardship practices. This is actually a lot harder and more expensive than it sounds. If you own land in the Amazon you are required to keep 80% of that land in forest, and a 30-meter strip of forest along your streams and ponds. The law is way more restrictive for Brazilian farmers than for American farmers. I predict that in another three years, Brazil will surpass the U.S. as the world’s agricultural superpower, and Amazon farmers will be demonstrating to the world how you reconcile environmental conservation, sound labor practices, and highly productive ranching and farming.

On top of this we’re seeing commodity roundtables begin to take hold, like the responsible soy roundtable (RTRS) that had its first general assembly three weeks ago. 20 percent of the world’s trade in soy is represented in the membership of the RTRS. Over the next two years, there will be a process of defining the criteria that define what constitutes responsible soy and is OK to buy. Meanwhile the international finance corporation (IFC), ABN Amro, Rabobank, and several other creditors are beginning to attach environmental conditions to their loans, the trend is quite pervasive.

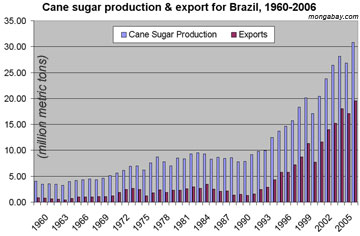

And while these are positive developments, the drivers of deforestation are stronger than ever. I do believe that tropical deforestation will go up before it goes down for two reasons. First, the high price of petroleum and other factors has driven up the demand for bioenergy, which means that the demand for new agricultural land is growing. We see soy prices going up partly because less soy is being grown in the U.S. As corn expands to meet the surging demand for the emerging ethanol industry. As sugar cane expands in Southern Brazil, soy production is heading northward, encroaching on the Amazon. Soy prices are also inching up because of the new demands for biodiesel (from soy oil). All these are factors drive up the cost of the commodity and basically make it profitable to convert land where it wasn’t profitable a short time ago. A second major trend that is increasing the demand for agricultural land—land which is in very short supply in the temperate zone but abundant in Brazil and some other tropical countries—is the “emerging meat-eating” economies, such as China and South Africa. Economic growth in these countries is creating an affluent class that is eating more chicken, pork and other meat that is raised on animal ration. Brazil is an important source of protein for this ration.

Mongabay: So it sounds like you are somewhat hopeful for increased sustainability of industry in the Amazon?

Nepstad: Yes, I am. There’s been a redefinition of strategies for important constituencies in the Amazon. For example small landowners and indigenous groups traditionally opposed negotiating with agroindustry and large-scale cattle ranchers. Today they are coming to terms with the idea that they can now cut deals with these guys without losing their heads (literally). A number of NGOs are in the same sort of transition. Some international NGOs may have taken this trend a little too far, by receiving money directly from agribusiness. While there’s a huge amount of controversy, the overall trend does seem to be towards more robust approaches to forest conservation that involve direct involvement with the main drivers of deforestation–ranchers and soy farmers.

Mongabay: How does China play into these developments? Are the accountability trends you’re seeing for commodity production applicable to Chinese-influenced operations?

Nepstad: There are some large Chinese companies that are seeking sustainable sources of agricultural commodities. China is not exempt from the greening of the commodity markets. This is very good news.

Mongabay: You’ve done extensive modeling of future chane in the Amazon. While we may see positive industy developments don’t we still have climate change looming on the horizon? What’s your outlook in terms of deforestation and climate change?

Aerial view of the first half of the 2004 burn, with the field sample grid overlaid. Courtesy of WHRC |

Nepstad: I think that land use change is by far the biggest threat to tropical forests over the next 10 to 20 years because of the growing pressures from commodity markets that I already mentioned. Enormous areas of tropical forest experience severe seasonal drought and are therefore vulnerable to forest fire. As cattle pastures and agricultural fields move into these fire-prone forests, forest fires will ensue. In 1998, the emission of carbon to the atmosphere from forest fire in the Amazon and Borneo alone was roughly equivalent to all of the carbon emissions that year associated with tropical deforestation.

Mongabay: What about climate impact?

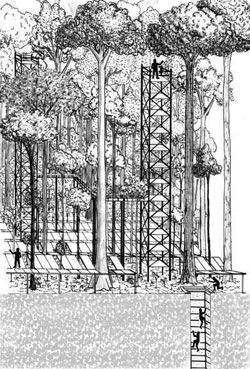

Slow-moving fireline on forest floor. Courtesy of WHRC  Three-dimensional sketch of the WHRC drought experiment. By Kemel Kalif, IPAM |

Nepstad: Through the Woods Hole Research Center and the Amazon Institute of Environmental Research (IPAM), we’ve done a lot of experiments to forecast the potential impact of changes in land use, fire regime, and climate on the Amazon.

For the past three years we’ve been burning a 100-hectare block of forest to see what fire return interval would have to take place before the forest is invaded by grasses and becomes so flammable that it could catch fire virtually any year. Our research indicates that a two-year return interval over a several year period might be enough for a forest to reach this state.

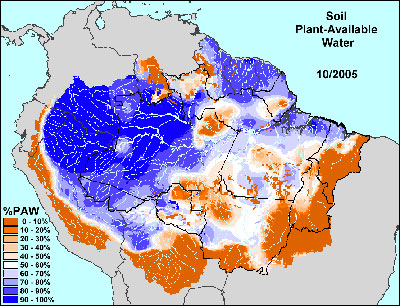

Further, there are several other factors that are pushing the Amazon towards a drier future, including fresh evidence that cattle ranches and pastures are less capable of generating rain than the forests they replace because they put less water vapor into the air–soy fields are even worse. On top of these changes in the vegetation itself we have rainfall-inhibiting smoke and the prospect of sea temperature changes–not just el Niño which we have always known creates drought in the Amazon–but the North Atlantic tropical anomaly like we saw in 2005 when we had record drought and record fires in the Amazon. The likelihood of that type of anomaly will increase with global warming. If we start to see sea surface temperature anomalies more frequently–either el Niño or the warming of the tropical North Atlantic (that occured in 2005)–then the area of tropical forest that burns could explode.

When we put all this together we come up with a very bleak outlook for the Amazon rainforest. I don’t have the final numbers, we’re running these right now, but it’s not out of the question to think that half of the basin will be either cleared or severely impoverished just 20 years from now.

The nightmare scenario is one where we have a 2005-like year that extended for a couple years, coupled with a high deforestation where we get huge areas of burning, which would produce smoke that would further reduce rainfall, worsening the cycle. A situation like this is very possible. While some climate modelers point to the end of the century for such a scenario, our own field evidence coupled with aggregated modeling suggests there could be such a dieback within two decades.

According to the WHRC, the above map is “a product of our ongoing drought monitoring effort from Oct. 2005, the worst month we have in our record going back to 1995. It shows moisture stored in the soil which is available for use by plants, what we call ‘Plant-Available Water’ or ‘PAW’, expressed as a percentage of the total water-holding capacity of the top 10m of soil at any given point; %PAW is one of the strongest indicators we have of severity of drought and of forest susceptibility to fire.. Courtesy of WHRC. |

Mongabay: Are reforestation and agricultural restoration viable options for some of the degraded areas that have been abandoned in the Amazon?

Nepstad: The forests of the Amazon have remarkable potential to regrow following clearing. Forest regeneration–without any help from people–is taking place on most of cleared Amazon lands that have been abandoned. It is really only after prolonged, intense use that this regenerative capacity is lost, or when fire invades. The prospect for agricultural restoration has been overstated. It is part of a robust, comprehensive approach to conserving the Amazon, but is not a panacea. About one fourth of the forestland cleared in the Amazon is abandoned and much of this land holds only marginal potential for sustained agricultural production because of restrictions posed by rock, poor drainage, impeding layers in the soil, and steep slopes.

Mongabay: So were definitely not out of the woods yet. Changing gears a bit, how did you originally get involved in the Amazon?

Nepstad holding a team meeting prior to the first big experimental fire in Brazil (2004). Courtesy of WHRC. |

Nepstad: As a kid I remember reading an article that described the soils of cleared forest land becoming as hard as concrete. That image really stuck in my mind. Growing up I was also a “lizard squeezer” or “zoo boy” — I definitely had a love for nature and wildlife. I finally got down to the tropics while I was getting my masters degree. I fell in love with it and moved to Brazil for a year when I started my PhD work. That was 1983. Basically I never left.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students pursing a career in the field?

Nepstad: There are a lot of places where people who are truly committed to this kind of work can volunteer, get plugged in and see what it’s really like to be embedded in these cultures and these landscapes. It’s not for everyone but if you do like adventure or living on frontiers it can be wonderful. I think the key phrase is to remain open to opportunities as they present themselves.

Mongabay: What can individuals do here in the United States do to protect rainforests?

Nepstad surveying WHRC’s ‘model’ pristine watershed (2006), Courtesy of WHRC. |

Nepstad: Even though most of the world dislikes us quite intensely, people look to the United States as a real role model. People in other countries see how we live our lives and try to emulate it. The fact that we have acted so irresponsibly in the global warming arena has certainly not helped conservation efforts. Therefore we really need to start getting our lifestyles under control, reducing consumption and waste. It’s what we do in our own homes, our own backyards, and our own communities that’s probably the most immediate thing we can do to help rainforest conservation. We need to set an example for the rest of the world on how we can live at minimal cost to the environment.

Beyond that I think there will soon emerge some real ways to channel money for rainforest conservation–I don’t think they are here quite yet. There are certainly organizations doing great work around the world and they need support. The carbon offset type schemes that are starting to emerge have potential though only some are effective. Finally, we also have responsibilities to understand what is going on outside U.S. borders and to realize the way we live is a lot different than people in the rest of the world. We have a disproportionate impact on the planet.

Mongabay: Do you have a favorite part of the Amazon Basin?

Nepstad teaching Ki Sede Indians downstream of an expanding agriculture-dominated watershed about where the water in their rivers comes from (2005), Courtesy of WHRC.

|

Nepstad: My favorite part of the Amazon is a place called Alter do Chão. It’s an indigenous community that developed ecotourism. My favorite thing to do is rent a boat for 4 days, sleeping on the white sand beaches of the Tapajos river, probably one of the biggest rivers that new or no people have ever heard of (its mouth is about 15 kilometers across]. The river is full of pink dolphins, gray dolphins, and fish and is flanked by forest: on the East bank is the national forest of the Tapajos; on the West bank is the protected extractive reserve of the Tapajos. On both sides of that river are many community-based projects for sustainable forest management, including one we’re involved with for reducing accidental burning of forest.

The area is beautiful and if you like the Amazon, it’s very relaxing.

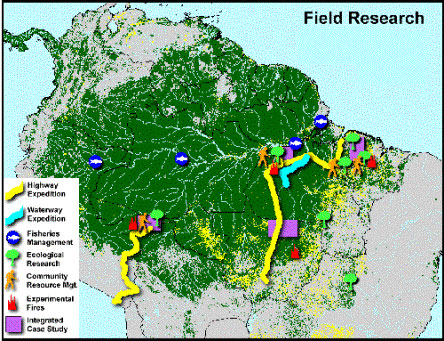

More on the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program

- Agricultural Expansion

- Amazon Scenarios

- Drought Simulation

- Fire and Savannization

- Logging & Family Forests

WHRC’s Amazon program. Courtesy of WHRC. |

Related interviews

|

John Cain Carter, founder of Brazilian NGO Aliança da Terra Cattle ranchers and soy farmers could save the Amazon — 06/06/2007 John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Aliança da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Aliança’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon. |

|

Dr. Philip Fearnside, Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus, Brazil Global warming could cause catastrophic die-off of Amazon rainforest by 2080 — 10/22/2006 For the Amazon, there is an immense threat looming on the horizon: climate change could well cause most of the Amazon rainforest to disappear by the end of the century. Dr. Philip Fearnside, a Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus, Brazil and one of the most cited scientists on the subject of climate change, understands the threat well. Having spent more than 30 years in Brazil and now recognized as one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest, Fearnside is working to do nothing less than to save this remarkable ecosystem. |

|

William F. Laurance, president of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation Rainforests face myriad of threats says leading Amazon scholar — 10/16/2006 The world’s tropical rainforests are in trouble. Spurred by a global commodity boom and continuing poverty in some of the world’s poorest regions, deforestation rates have increased since the close of the 1990s. The usual threats to forests — agricultural conversion, wildlife poaching, uncontrolled logging, and road construction — could soon be rivaled, and even exceeded, by climate change and rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. |

|

Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team Indigenous people are key to rainforest conservation efforts — 10/31/2006 Tropical rainforests house hundreds of thousands of species of plants, many of which hold promise for their compounds which can be used to ward off pests and fight human disease. No one understands the secrets of these plants better than indigenous shamans — medicine men and women — who have developed boundless knowledge of this library of flora for curing everything from foot rot to diabetes. But like the forests themselves, the knowledge of these botanical wizards is fast-disappearing due to deforestation and profound cultural transformation among younger generations. Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team, is working to stop this fate by partnering with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests. Plotkin, a renowned ethnobotanist and accomplished author who was named one of Time Magazine’s environmental “Heroes for the Planet,” has spent parts of the past 25 years living and working with shamans in Latin America. Through his experiences, Plotkin has concluded that conservation and the well-being of indigenous people are intrinsically linked — in forests inhabited by indigenous populations, you can’t have one without the other. |

|

Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden Biodiversity extinction crisis looms says renowned biologist — 03/12/2007 While there is considerable debate over the scale at which biodiversity extinction is occurring, there is little doubt we are presently in an age where species loss is well above the established biological norm. Extinction has certainly occurred in the past, and in fact, it is the fate of all species, but today the rate appears to be at least 100 times the background rate of one species per million per year and may be headed towards a magnitude thousands of times greater. Few people know more about extinction than Dr. Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden. He is the author of hundreds of scientific papers and books, and has an encyclopedic list of achievements and accolades from a lifetime of biological research. These make him one of the world’s preeminent biodiversity experts. He is also extremely worried about the present biodiversity crisis, one that has been termed the sixth great extinction. |