- An Interview with John Cain Carter.

- The key to making conservation successful is making it profitable. John Carter may hold that key.

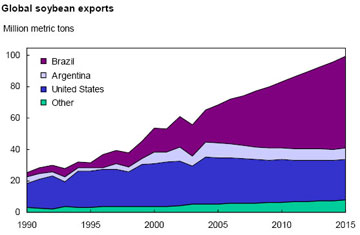

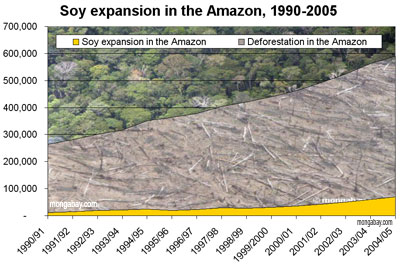

Since the early 1970s, environmental groups have spent billions of dollars on conservation efforts in the Amazon, but have failed to slow the destruction of its rainforests – the Brazilian Amazon has lost more than 700,000 square kilometers (270,000 square miles) of forest in that time. As donor dollars poured into the region, deforestation rates continued to climb, peaking at 73,785 square kilometers (28,488 sq mi) of forest loss between 2002 and 2004, before falling sharply in 2005 and 2006 due to declining commodity prices. To many, it’s become apparent that the market, not conservation measures, will determine the fate of the Amazon.

The reasons for land-clearing in the Amazon are compelling: cheap land, low labor costs, and booming demand for commodities driven by a surging China and growing interest in biofuels. These factors have helped Brazil become an agricultural superpower – the world’s largest exporter of beef, cotton, and sugar, among other products – in less than a generation. Amazon landowners have seen their land values double every 4-5 years in areas that just a decade ago were pristine rainforests. The market is driving deforestation.

John Cain Carter with his Xavante Indian neighbor |

Given this landscape, John Cain Carter believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter is a Texas rancher who moved to the heart of the Amazon 11 years ago with his Brazilian wife, Kika, and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Aliança da Terra. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed.

While deforestation rates in the Amazon have accelerated, the problem is not a lack of laws, but rather a legal system where enforcement is so slow and so corrupt that it renders the laws effectively useless. On paper, cattle ranching in the Amazon may be the most restricted in the world, with landowners required to keep 80 percent of their land forested – a limitation no rancher in Texas faces. Carter wants to see farmers in Brazil benefit in following the law, by turning this restriction into a marketing advantage. However in order to do so, Amazon producers have to ensure that consumers ( i.e., buyers of commodities like McDonalds, Wal-Mart, and Cargill) can confidently say that agricultural products are produced legally and even more sustainably than stipulated by the law. The incentive for producers is market access: Aliança da Terra helps Brazilian farmers and ranchers get the best price for their products, but only if they follow the rules. While producers get higher prices for their goods, buyers like Burger King and Archer-Daniels Midland can say they are using legally and responsibly produced beef. Meanwhile more rainforest is left standing, ecosystem services preserved, and biodiversity conserved. Everybody wins.

|

Accountability has other benefits. Aliança da Terra’s growing clout even helps fight corruption – officials know they can’t solicit bribes from Aliança’s members while members know that passing bribes will only get them kicked out of the system. The promise of Aliança da Terra is so great that conservation groups and landowners are sitting down at the same table, when just two years ago they were the most bitter of adversaries – a substantial achievement and one that bodes well for the success of these efforts.

What is most remarkable about Aliança’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these mechanisms with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon.

In a June interview with mongabay.com Carter explains his experiences in Brazil and his approach to saving Earth’s largest and most important rainforest.

INTERVIEW WITH JOHN CAIN CARTER OF ALIANÇA DA TERRA

Mongabay: You were born in Texas, so how did you come to be involved in agriculture in the heart of Brazil? How long have you been ranching in South America?

Carter with his Cessna in Mato Grosso. Image taken by Woods Hole Research Center scientists the day a section of Carter’s forest burned due to “bad” neighbors. |

Carter:

I’m originally from San Antonio, Texas, but after college I was in the service and then did a graduate ranch business management degree at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, Texas. Basically this was an MBA program for cattle production. While I was there I met my future wife who happened to be Brazilian. To make a long story short we got married and moved down to Mato Grosso, a state in the Brazilian Amazon. We’ve now lived there for 11 years.

Mongabay: So it sounds like for an American farmer you were ahead of the curve in terms of seeing the potential for agriculture in Brazil.

Carter:

I suppose you could say that. When we moved down here there were no Americans here. It was, and in many ways still is, very much a frontier area. The interest in agriculture here has really just taken off in the last 3-4 years and there were no Americans here until very recently.

Mongabay: Do you think growing interest in biofuels and rising demand from China are driving this change?

|

Carter:

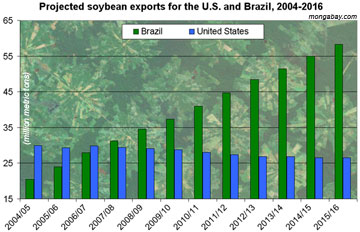

I think interest certainly increasing because of these factors, though soybeans were already getting big here before the biodiesel craze, mostly because the cost of production is so much lower here. A couple of years ago you saw a lot of concern among U.S. producers of beef and soy that Brazil was going to outproduce the United States in production from this point forward. The climate, the amount of open land, the lack of freezes, and higher yields all make agriculture here very attractive. Foresighted people could see that it wasn’t going to take a lot for Brazil to get its feet under its legs. Sure enough, Brazil is now the leading exporter of beef, cotton, sugar, orange juice, coffee, and cacao. It’s second in soybeans, but not for long. The country has become an agricultural powerhouse.

Mongabay: Can you describe the sort of environment where you have your ranch? Is it former rainforest, surrounded by rainforest, or cerrado grassland habitat?

Carter:

When I first came to the ranch is was 60 percent forest and 40 percent pasture. Most of the forest was secondary forest that had been previously deforested but had regrown. The ranch is located in the southeast Amazon forest–the so-called transition forest in northeastern Mato Grosso. Most of that region was forest but I’ve witnessed the vast majority of that area cleared over the past 10 years. It’s been very fast-paced progress with the frontier rapidly moving across the Amazon. Just a short time ago we had wilderness, but now we have Cargill at our back door.

Mongabay: What about the laws that require ranchers to keep a portion of their land forested? Has this not slowed deforestation?

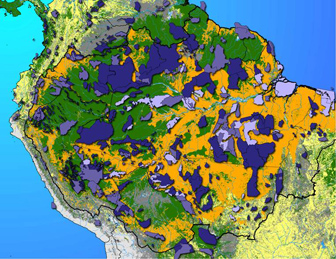

Total deforestation and area of soybean cultivation across states in the Brazilian Amazon. Overall soybean cultivation makes up only a small portion of deforestation, though its role is accelerating. Further, soybean expansion and the associated infrastructure development and farmer displacement is driving deforestation by other actors. Note: some soybean farms are established on already degraded rainforest lands and neighboring cerrado ecosystems. Therefore it would be inappropriate to assume the area of soybean planting represents its actual role in deforestation. |

Carter:

Yes, since I arrived here there’s been a forest reserve law in place. Actually in 1998 they raised it from 50 percent of your land kept as forest to 80 percent. That provision really backfired for the environmental movement. The law was already contested at 50 percent. Raising it to 80 percent just created a mass hysteria and a state of civil disobedience where landowners said “to heck with this” and just tore down everything.

The fact is, most people never respected the 50 percent requirement in the first place. For the most part, they just classified rainforest as cerrado so they could clear more land.

The problem stems a system that is essentially a corrupt, black market. The agencies that control the permits and law enforcement are on the take, so it basically is just a bribery process. While this has changed a little bit in the past couple years, there’s still a lot of funny business. For example, the big story in the paper yesterday was a sting where they busted a whole ring of illegal loggers. A bunch of these guys worked for the environmental protected agency and the parks and wildlife agencies.

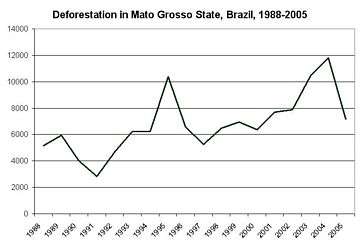

Deforestation in Mato Grosso State, Brazil, 1988-2005 |

There is very much a frontier mentality here. The return on land appreciation is so great and the justice system so slow, that by the time you catch a landowner, he’s already sold the land and made a fortune. There’s no real incentive for people not to do it and they could really care less what an American, Frenchman, Dutchman, or anybody else in the international community thinks because there are no repercussions for their actions. That’s one reason why we started this program–we’re using fire to fight fire by using market access as a carrot to encourage people to do the right thing. We’re providing economic incentives and people want to be a part of it.

Mongabay: Sounds like a difficult situation. What kind of land appreciation are we talking here?

Expanding Deforestation in Mato Grosso, Brazil This pair of images shows large clearings made in the Amazon Rainforest in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil, between 2001 and 2006. NASA images by Robert Simmon, based on data provided by the NASA /GSFC /METI/ ERSDAC/ JAROS, and U.S./Japan |

Carter:

In our region you can pretty much expect 7-15 percent annually and that’s a pretty conservative estimate. In 1999-2000 our land was valued around 150 reais per acre. Our neighbor just sold his land for 833 reais per acre. So that’s more than a five-fold increase in seven to eight years. The returns can be higher depending on whether you buy forest, regrowth, or open area. The real play down here in on land appreciation, not the commodity you are producing. I don’t think most people understand that. Most people come here looking at figures on crop production and yields. I think it still has a long way to go since Brazilian institutions are getting stronger and you’re going to see institutional investors start pumping in money which will further drive land prices. The ethanol and biodiesel trend is pushing up prices as well.

Forest land is by far the cheapest but with all the pressure on the Amazon today. people who have a lot of exposure really tend to shy away from forest, because they don’t want to be caught in the spotlight and put in the paper. If they stay within the law, they are fine, but most people don’t do that. Most multinational corporations today wouldn’t touch forest land with a 10-foot pole due to the negative press. Most people are looking for cerrado lands that have already been cleared so they don’t have to do the crime. That leaves forest demolition mostly to investors who don’t really care about public opinion. A lot of time they are dealing with land that has no title or title problems or land invaders. That’s where the real opportunity comes. They go in there, get it for cheap, fix it up, and try to get their title in order before they sell for a hefty return.

Mongabay: Is there any record? Is there a way to prove forest was there a year ago?

Carter:

Yes, they can prove you tore down forest in the past two weeks using satellite imagery or the state monitoring system but the problem is the corruption and payoffs that ruin the system. Fine are rarely collected, but bribes are common. If they wanted to, they could enforce the law immediately. Actually, prosecution is happening more these days. I think international pressure is a factor.

Brazil’s satellite monitoring system is one of the best in the world. If needed, you can tell if someone deforested their land 15 years ago. For my old property, I can get annual satellite imagery from 1979 to the present.

Mongabay: Why did you get involved? Why do you care about the sustainability of ranching in the Amazon?

Carter:

My first visit here was in 1993. My wife’s dad had a ranch and was helping him look for some more land. I drove up with him to a small town on the edge to the cerrado and forest. The dirt road took us through the forest of the southern Amazon. On the way, I saw a Xavante Indian walking naked along the road with a bow and arrow in his hand and a black jaguar in the highway. I knew this is where I want to be so I moved here.

Carter’s plane over Mato Grosso  View from Carter’s airplane window during the burning season  When the smoke clears, it is not a pretty site |

I flew down from the U.S. as a pilot and moved to this property. Since the infrastructure here was terrible, we usually got around by airplane which gave me a really good perspective of the scale of what was going on down here. We lived on the frontier in the truest sense of the world. For five years we had no electricity, no telephone and no neighbors. We got a real dose of what’s happening. I don’t think many people have experienced this firsthand–certainly the environmental groups haven’t. Their perspective is from 10,000 feet or from their air-conditioned offices in Washington, D.C. Sure they pop in by parachute every now and again, but they don’t live here and sense what’s really happening. We lived this kind of lifestyle for over ten years. We saw the corruption firsthand. We, like everyone else, would hear loggers on the shortwave radios warning of a proposed IBAMA (Brazil’s environmental protection agency) raid. Sure enough the loggers would have bribes in hand, waiting for IBAMA to arrive. At one point there were more than 100 unlicensed saw mills in the area, though now there are none — there’s little harvestable forest left.

I saw this on a day-to-day basis as I flew. I’ve now flown probably somewhere between 700,000 and 800,000 kilometers in the state and seen what seems like the whole thing deforested in 12 years. On the ground it can be even worse. Our neighbor one time tore down 12,000 acres of forest in three months. We couldn’t see for about 4 weeks when he burned the residual–the smoke was so thick. During the burning season in the Amazon it’s like this all over. You can’t describe it unless you’ve been there and seen it. You can’t see the sun at mid day and have to drive with your headlights on. It was terrible.

It was clear that environmental groups hadn’t had much of an effect in slowing deforestation. They’ve been effective at making the world aware of the problem but they have never come up with a real solution to the problem. The slowing of deforestation the past couple years was not due to their efforts as the minister of the environment likes to claim, it was the market. People went broke and no one had money to invest in deforesting. Landowners only clear forest when they have extra money in their account–they do it out of their own cash flow and private equity, they don’t use loans.

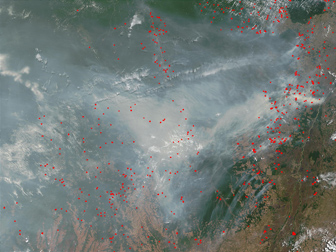

Acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on June 30, 2003, this image shows a portion of the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. Intact forest is dark green, while cleared land is tan or reddish-brown. Mato Grosso is located on the southern edge of the Amazon, east of Bolivia. Image courtesy Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC  In the Mato Grosso region of Brazil, fire (red dots) is a major cause of deforestation. “Slash and burn” agriculture is used to clear tropical forests for farming and ranching, and this series of Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) images shows the resulting transformation of the landscape. Lines and geometric shapes reveal where plots of land have been converted to agricultural uses. In many of the images, the Xingu National Park hangs like an appendage off the broad expanse of Amazon rainforest to its north. Credit Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC |

Anyway since the environmental moment was not accomplishing much of anything with the hundreds of millions they spent a year to try to stop it, my wife and I decided to try. We were pretty disillusioned with the environmentalists because they never seemed to confront the problem: economics. They were always trying to create a villain to blame and a colorful bird or mammal to save. As landowners we could see opportunities that the environmental movement had missed.

My wife and I decided that amongst other things, including all the violence in the region which, on occasion, impacted us personally, we weren’t going to stay in the area unless something was done to change it. We could not continue to sit and witness this rape without at least trying something.

So that’s how we started the idea. We went on all the wrong trails and all the naive roads that people seem to take. We banged our heads against the wall and realized there was no way to stop it–the momentum is just too great. The one thing we could do was try to minimize the collateral damage by creating incentives for people to at least maintain forest in riparian zones and as corridors between properties. If we got that done, we would accomplish more than anyone had done in the whole history of the Amazon. So that’s where we concentrated our efforts. We lowered the bar enough so that we knew landowners would jump if they had a small incentive. The carrot is market acceptance for their products. We believed at least 30 to 40 percent of the forest in the Xingu region could maintained in a pilot project. We’d then aim to expand the program to frontier regions.

Mongabay: How does Aliança da Terra work?

Carter:

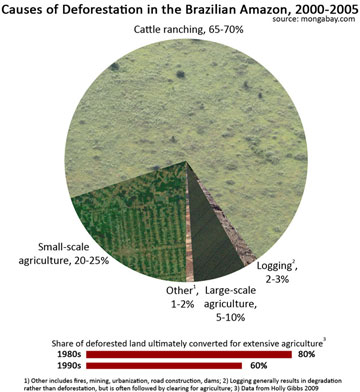

Aliança da Terra is based on the concept of market acceptance for sustainable agricultural production in the Brazilian Amazon. We’re presently focused on beef, which is the largest driver of deforestation in the Amazon, though we’re also working with other products including soy. Aliança da Terra is doing the necessary field work first to prepare for an all out attack on the markets, demanding recognition of the ecosystem services being provided by private land owners through market access. This gives a tangible incentive to farmers and ranchers who farm in a responsible manner and obey good land stewardship practices as well as the forest code and excludes those who don’t. Our reasoning is that this land is going to be deforested regardless of the law or public sentiment if some immediate, tangible economic incentives are not installed asap. The soy boycott by Greenpeace was a sign of how globalization can touch conservation. It helped to prep the battlefield for us, showing that the world is starting to pay attention to how food stuffs are produced. But, the flip side to that is that the world needs to work with producers as well as make adjustments along the supply chain on how margins are distributed. Now it is not a fair and equitable distribution, more should trickle down to the producer/land owner as he is the one with the conservation burden/ecosystem service on his back. This needs to be itemized on the balance sheet!

Landowner with Aliança da Terra staff |

We’re setting up an accrediting mechanism that will help responsible landowners gain access to markets and get the best price for their products. The timing for this is perfect with international pressure forcing landowners to face these issues head on. The landowners like our system because they have a say in the creation of standards and a vested interest in making it economically viable. Getting landowners on board was key. We knew there would be huge repercussions if people thought there’s just another non-profit coming in and we also built it to be Brazilian and not a foreign entity. Other than myself everyone here is Brazilian.

We’ve built an accrediting mechanism that allows consumers to use their purchasing power to select between environmentally responsible producers and environmentally irresponsible producers. By doing this, we’ve effectively created an incentive for producers here to do the right thing.

Mongabay: Does this mean you are seeing “pull” from consumers who are asking for certified products?

Carter:

That’s a tricky question. With mounting worries about global warming reflected in Al Gore’s movie, there’s no doubt the world is more concerned principally with what’s happening in the Amazon. The international community sees where we are going to be in 100 years, and it’s not a pretty picture. In even the best case scenario, we’re still kind of in trouble, while under the worst case, we’re toast. In the best case scenario we still need to take action. This outlook gives us enormous room to work and a wide range of options. Environmental groups and the international community have basically prepped the battlefield for us, so the world is prepared for what we’re creating. It is already looking for solutions like this.

This pie chart is based on the median figures for estimate ranges. Please note the low estimate for large-scale agriculture. Between 2000-2005 soybean cultivation resulted in a small overall percentage of direct deforestation. Nevertheless the role of soy is quite significant in the Amazon, displacing small landholders who then clear virgin forest areas. Further, according to Philip Fearnside, a leading Amazon expert, soybean farming also provides “key economic and political impetus for new highways and infrastructure projects, which accelerate deforestation by other actors.” |

For the most part, the consumer always wants to buy the cheapest product on the shelf. If someone is willing to pay a premium because of conservation, it’s called a niche market. Niche markets will never stop the deforestation of the Amazon. We have to hit the commodity markets and spread the benefits across the whole region, not just a niche sector. To do this, we can’t raise the price of the commodities–people simply haven’t shown a willingness to pay more for these products on a consistent basis.

Under our system, the only benefit a producer will get is market access, but by gaining access to the European, American, and other foreign markets, local producers will benefit significantly. Instead of having prices based on the Brazilian Bolsa, they will be getting Chicago mercantile rates which are inherently higher, less freight and trade tariffs. The only way producers have this access is by following the rules. We are essentially creating a hurdle that’s effective for conservation and low enough to be attractive, but that allows you to jump to that higher price and even get bargaining power with slaughter plants and the big grain brokers like Cargill, Bungee, and ADM [Archer Daniels Midland]. Currently the big guys have the leverage. The real reward is going to come from money that already exists in the system but is currently staying in the pockets of the big guys. We’re trying to reach critical mass of volume that we have market leverage. We are absolutely convinced that once this happens, and you have two products, one with credibility and transparency and the other with a questionable origin, people will choose the option with legitimacy.

An added benefit for producers is that our system reduces the risk of a moratorium on Brazilian products. While the EU may slap a beef or soybean on Brazilian agriculture, certified products would stand a better chance of escaping sanctions.

Mongabay: So you are offering a path to markets?

Carter:

Exactly. We offer a ticket to the market. We also look for other financial incentives for producers that participate. For instance, cheap money through loans used to reforest their riparian zones, lower interest rates, and financing for production. Most of the big investment banks are looking for prerequisites before they lend money and it appears some of them will be adopting our policies. We’re trying to facilitate two bottlenecks in the beef industry: when you want to get money and when you try to sell. We’re not saying you’re going to get paid more for your product, but you’ll get a pathway to the market, which in and of itself, is more lucrative because they are going to be getting prices based on the Chicago Mercantile rather than the local market.

Credit Aliança da Terra |

We have the largest livestock association in the world on board, the Associação Brasileira dos Criadores de Zebu [the Brazilian Zebu Cattle Raisers Association] (ABCZ) involved. It’s a registered breeders association, the most prestigious in Brazil, with 16,000 ranchers. They are going to start requiring their members to participate, using Aliança criteria on their property. It’s similar to a land registry. We started a pilot project in Xingu and Mato Grosso and we’re planning to expand it to the whole country. Within 2-3 years we’ll be in ten states. It’s extremely exciting — we’re doing just as we hoped.

Mongabay: So ranchers are enthusiastic about the project because of the legitimacy and financial inventive? That is, you’re not dragging them on board kicking and screaming?

Carter:

To be honest, we were a little hesitant at the start, thinking that we were going to have trouble signing them up. We feared negative feedback, but from the start people were very enthusiastic. They told us, “This is exactly what we need. We’re tired of being branded as bandits.” Now we’ve gotten a huge resounding applause from the sector.

Being a landowner here is complicated. When you live in this region, you see the corruption. People involved in the take are supposed to be protecting the forest so it’s no wonder that you get the state of civil disobedience among landowners. There’s no real honest leadership to set an example. So when we come in and offer them a path of least resistance to the right thing as well as hanging market incentives, landowners jump at it.

Settler participant with Aliança da Terra. Credit Aliança da Terra |

We want market recognition for shouldering this conservation burden. Where else in the world do you have landowners who have to keep 50 percent of their land forest? Nowhere. If the consumer is supposed to benefit people for doing that then you tip the scales back in favor of the landowner and its going to create more positive feedback for people to follow the rules by maintaining the forest. As it is right now there’s nothing to keep forest standing because the law doesn’t catch you in time and you can always bribe your way out of it if you do get caught. You might as well tear it all down since the your land value shoots up and you can also produce a lot more product on your property. You’re more profitable. When you look at the numbers it doesn’t take 5 minutes to understand why its all coming down.

We’re trying to turn this forest reserve law from a negative into a positive, or make lemonade out of lemons, so to speak. People think farmers in the Amazon are bandits so we’re trying to show there are good people who are trying to make a difference and reduce their impact. Working with some magazines to make it more meaningful, we’re going to have a landowners award ceremony every year where we recognize the best land steward. No one’s ever patted these guys on the back or even shown them how to do the right thing. All they’ve told them is no. The officials fine them and extort them, often at the same time. Meanwhile the whole production system is opaque. For example, the vast majority of beef that’s produced in Mato Grosso state is for export but it’s hard to pinpoint the origin of the beef. Slaughter plants do a good job of hiding it. We’re turning the system on its head, adding transparency and credibility to turn it into a worldwide example of good land stewardship. Producers will be rewarded through market acceptance for taking the extra steps to do the right thing. They’ll be able to take their product to McDonalds, Burger King, and other firms worried about reputations. All the big multinationals want credibility these days in regards to the environment and sustainability.

Mongabay: So you’re really addressing the supply chain for these large companies?

Carter:

We’re confident that we can become providers for the world. McDonald’s regularly gets blasted in the press for their links to environmental damage. Mostly recently Greenpeace traced Amazon soy all the way to Holland where it was used to feed chickens that went into chicken McNuggets. When that story broke, it was huge news and sparked the moratorium on Amazon soy by the big crushers. It has forced producers to be accountable for the sources of their soy to the most distant part of the supply chain–the properties where the soy is produced. Anything coming from deforested land after a certain date is no longer acceptable.

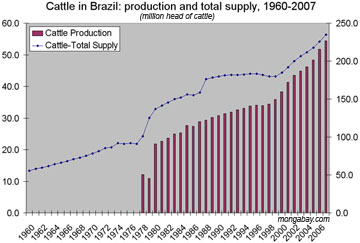

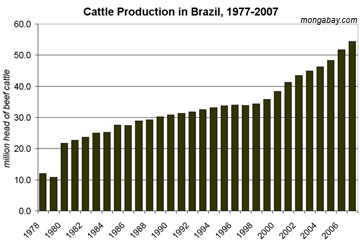

Cattle production in Brazil, 1977-2007

|

We want to be prepared to create the same thing for beef–the guy who really helped orchestrate the soy effort is one of our board members Ocimar Villela. Essentially we want to reward people who are obeying the forest code and doing good land stewardship practices. We now have management for 3 million acres with approx. 300,000 head of cattle grazing on these acres, that’s twice the size of largest branded beef herd in the United States. And that happened in 6 months. We’ll have ability to use our branded cattle to supply all of Wal-Mart South America or provide grain feed to McDonalds for their chickens in Holland and guarantee that they were produced with this criteria.

This is why the process has taken a long time–we’re attacking a commodity. By attacking a commodity, we’re changing the way production is done. Hopefully it will change how its done worldwide for the future. We hope that someday a rancher in Texas and a sheep farmer in Australia will be bound by the same criteria for land stewardship.

In the end, what started under the worst possible conditions in the heart of the Amazon, could be the criteria for producers worldwide. That’s our dream. That’s also what the World Bank wants to see, as do other financial institutions. I think that’s why we’ve won support from some many influential institutions, like Woods Hole. This can have an enormous impact across the globe.

Mongabay: So you are anticipating a moratorium on beef?

Carter:

Yes, it’s the logical next step after soy, especially since two-thirds of deforestation is for cattle pasture. I think that in some ways a moratorium is really a good thing. I’ve seen the whole go up in smoke and I believe that if you can’t beat them, join them, and then try to make change from within the system. You have to work with the landowners, give them incentives or otherwise they are never going to do anything. We’re trying to be proactive.

Credit Aliança da Terra |

The fact is, we’re doing this in the eye of the hurricane. Just outside of the Xingu is probably the world’s worst deforestation, outside of Africa. Roughly 70 percent of the deforestation in the Amazon basin is happening in that part of Mato Grosso. So if we can make it work there it will be a real achievement. Anything that works there can then be adopted in other states in Brazil.

But I think we can take it beyond the Amazon. I’ve been contacted by some associations in the United States, the USDA, and academia about the system. I believe we could see it adopted in as soon as 5 years in the U.S. Among the groups showing the most interest are financial institutions, which are looking for greater accountability. They are developing prerequisites for loans so that no matter where a producer is located–be it a producer of soybeans in Brazil or a sheep farmer in New Zealand–there will be a universal set of criteria so that we can even the playing field worldwide. The World Bank is looking for something that can be duplicated on a global scale, which is exactly what we are trying to create.

The certification system is flexible to allow for differences in state or national forest code systems, but requires the same application of general land stewardship practices. This allows the system to work for any country across the world for virtually any agricultural product. For example, if you look at my home state of Texas where you have a lot of environmental degradation, ranchers are presently selling beef to Japan without any restrictions whatsoever. By comparison, a ranch in Mato Grosso is required to be 50 percent forest, a huge conservation burden for which Brazilian landowners see no compensation. This forest produces X amount of carbon sequestration service per year, an ecosystem service I’m providing but getting no benefit from it other than market access, whereas a person in East Texas who cleared his Piney Woods forest down to the edge of the Brazos River is not penalized for it. That creates an uneven playing field that I think goes back in the face of people in the States and Europe who threaten to boycott Brazilian products. In America you have all sorts of agricultural subsidies, in Brazil there are no subsidies and you have this added conservation burden on your shoulders. There’s nowhere else in the world with such a restrictive forest code as Brazil has. But it’s the only reason you still have some forest here today — otherwise it would all have been clear cut.

Mongabay: There are a number of certification schemes with varying degrees of accountability and effectiveness around the world? How does yours differentiate itself in this market?

Aliança da Terra office staff |

Carter:

We offer consumers confidence instilled by the involvement of impeccable organizations like the Woods Hole Research Institute and researchers from Yale, Stanford, the University of Sao Paulo and NASA. We have some of the top naturalists and environmental scientists in the Amazon involved with this. Some of them are our best friends and I have nothing but respect for these guys. They’ve stuck their necks out there to jump in bed with producers. Same with producers. They’ve really had to put a lot on the table to work with groups they usually see as adversaries. So we offer legitimacy from both industry and scientific perspectives. We have the best possible credibility in terms of how the market perceives us. Though our internet-accessible satellite imagery, we offer end consumers the ultimate in transparency: they can see the very properties where they beef or soy they buy is being produced.

Finally we are also working on getting the buy-ins from all the other nonprofits in the region working on these issues. There’s a lot of interest because the concept is win-win and scalable on a global level for virtually any product. We even have the development banks wanting to be a part of it. Everyone agrees something has to be done.

Mongabay: I spoke with Dr. Dan Nepstad of the Woods Hole Research Center last week. He’s played an important role in this process, right?

Carter:

Dan is the backbone of all of this. From my perspective as a layman, he has to be one of the most important figures in the Amazon today. He’s combined the environmental movement with sound science and has had more of an impact than just about anyone I know and really gotten little credit for it. He’s very humble but has done an absolutely phenomenal job.

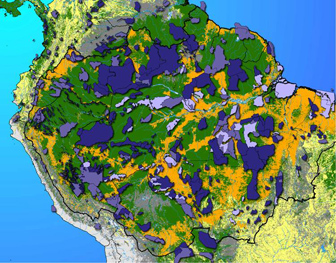

Woods Hole Research Center projection of Amazon forest cover in 2050 assuming a “business-as-usual” scenario. Credit: Woods Hole Research Center Woods Hole Research Center projection of Amazon forest cover in 2050 assuming a “governance” scenario. Credit Woods Hole Research Center |

The funny thing is, we didn’t start on the same page. Back in 1999 he was quoted in a magazine talking about deforestation laws in the Amazon. I was quite disillusioned with the environmental movement and what he said really upset me so I contacted him, more out of frustration than anything. Forest was coming down so quickly and no one seemed to be doing the right thing to stop it. I challenged Dan on his contention that raising the forest reserve requirement from 50 to 80 percent was a good thing. I explained that as a pilot that I could see that the new law had done just the opposite, raising the deforestation rate exponentially. As a landowner I knew that people on the ground were saying “to hell with this, I’m just going to cut it all down.” I invited Dan to come visit Mato Grosso to see for himself from my airplane. He responded the next day and within two weeks he was down here with two of his researchers from IPAM (Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia) who then spent 5 days with me. On the day we landed back in Goiania he said, “John, I’ve been working 20 years in the Amazon but you’ve changed my perspective on deforestation.” I told him the idea for trying to leverage markets and bring in landowners using incentives instead of beating on them, since beating on them hadn’t done anything. He shook my hand that day and said, “John let’s do it.” That was our agreement and since then he’s been the heart and soul of this deal and the reason I’m doing it. If it wasn’t for him I would have jumped ship because the odds are just insurmountable.

The Brazilian government, international community, and environmentalists have taken the wrong approach here. We’re now working to convince the world that they have to work with people who own the forest. Dan truly bought that idea and saw the potential and then sold this it to the power brokers and deal makers. He sold it to the big nonprofits that would pretty much be intimidated by this kind of idea or feel threatened by it. Now through Dan we’ve been able to lobby these groups and have them participate as allies to create something that’s bigger than all of us.

|

Dan has helped the governor develop policies that have changed the way business is done in the state of Mato Grosso. Dan didn’t get credit for it but I was there in the meetings and saw his influence at work. He is a very important person today. If anything changes in the Amazon he will be one of the key people who has made it happen, so he has all my respect.

Dan has penetration internationally too. He knows very key individuals other than environmentalists, including Michael Jenkins who is the head of Forest Trends which is tied in with the Katoomba group, a think tank of business leaders from different industries who look for market solutions, including ecosystem services and carbon trading. So Dan’s has a deep network of contacts among international industry, governments, scientists, and environmentalists while I have penetration here with the landowners–that’s why we joined hands. He knew we had something special that could really change things for the better in the Amazon. It’s been a tough process but it looks like its starting to work.

The pendulum is swinging back in the other direction. I’m pretty conservative, but in 5 years I think we are going to look back and say it worked. Companies like Wal-Mart, Burger King, McDonalds, and the largest grocery store chain in Brazil Pao de Acucar are all starting to sniff the winds and it looks like they are going to start doing something like we’re doing. A European Union certifying company, Eurepgap, that certifies properties producing commodities for export to the European Union is in contact with us trying to establish environmental criteria for agricultural products from the Amazon for the first time. What we’re building could become a prerequisite for export to Europe and possibly for loans from the World Bank, IFC, and commercial banks. If this turns out to be the case then this will really be a success. Whatever forest remains today in this region is the result of everyone involved in this process — otherwise it wouldn’t be there. A lot of this is coming from a pilot’s perspective from seeing the whole country, most of which was at one time forested. All of Sao Paulo and Parana state, the southern states were Atlantic rainforest but now there’s 3 percent left. There’s no forest on the streams — they are denuded of riparian forest cover and there’s no reason to think the Amazon wouldn’t see thing same thing. It will be the same thing in 50 years if something isn’t done — it doesn’t matter what people say. It’s an overwhelming firestorm that you just can’t fight the methods they are using today. You have to bring in economics or else you have no chance.

Mongabay: Are you making any efforts to recoup the value of carbon credits, for example seek some kind of compensation for that service?

Carter:

Today there are no are carbon sequestration credit programs in the Amazon using native forest. The only carbon credits paid are for hydroelectric dams and reforestation projects using eucalyptus, pine or rubber trees. There’s zero for native forest. However we recognize that this may change in the future so we’re using our project as a pilot. We’ve selected 10 ranches across the region and are working with scientists to measure the growth rates of trees in each different region to see how much carbon they are sequestering by reforesting riparian zones. One of our board members is Michael Jenkins of Forest Trends, a group that is at the cutting edge of payments for ecosystem services. When binding carbon emissions limits come into effect we’ll be ready. For now all this is pretty much pie-in-the-sky, but in ten years I think this will be tangible. The producers ask about it but we tell them not to hope for that because it’s not going to happen for sometime. Down the line it will be a bonus for them. We’re building the system to be worthwhile even without carbon credits.

Forest near Carter’s ranch. Nearly all of this has now been cleared. Credit Aliança da Terra Typical dry season burning near Carter’s ranch. Credit Aliança da Terra |

One the most interesting things we’re doing is collecting scientific data across our properties which are widely scattered across the state. We have rainfall data going back 15 to 20 years for some of the sites. This is data that neither scientists nor the government has, and could be used for drought monitoring and climate change forecasts. We’re also training all employees at the ranches to do scientific transects and count species so they can do mammal inventories at selected properties. These efforts are creating a quantified data set across a wide area. This will help scientists understand the distribution of species across the region as well as the impact of fragmentation, forest regrowth, and climate change on species composition. For example, we found an endangered species of saki monkey on my ranch. It was surprising since it was well outside the given range for the species.

There are any number of side projects involving biodiversity conservation in the Amazon. For example, I have a side project with Amazonian river turtles. We’re trying to rehabilitate them after overhunting. We have teams that go out to collect the eggs after they are laid in June-August. We raise them until they are about 2 months old which increases their survival rate exponentially. We’re working with the federal government on this project.

Anyway, in this end these are powerful tools that will let landowner know what their properties hold. These maps will unlock the value of their land for other than cattle.

Mongabay: Could you give an example of a corrective action you would recommend for a landowner?

Carter:

We concentrate on four primary items. The first is riparian zones along waterways and swamps. By law those areas are supposed to maintain 50 meters (160 feet) of forest cover on each side. Few people have done this. Instead pretty much all the forest is torn down leaving creeks and streams as muddy drainage ditches. To qualify for certification, landowners need to let these areas recover naturally or reforest them.

Similarly there are legal requirements to maintain forest on 80 percent of your land. If you have a deficiency of forest on your property then you have to sign a legal document that says you will come into compliance over a certain timeline or that you will compensate in another area in the same watershed. Our property for instance, lacked around 1200 hectares of forest when we moved to it, so I let a portion of our property come back naturally to meet the forest code. I did it on my own — there was no pressure from the government. Coming from the States, I thought I had to come into compliance with the law. Turns out that I was among the 5 percent or so in the state who is actually in compliance..

Another corrective action is reforested hills and cliffs to control erosion. This is probably the second most important work after riparian zones since all the eroded soil ends up in streams where it changes the pH, the turbidity, and the fisheries.

The third area is farming methods. We encourage the use of contours, no-till, terracing, and other soil conservation methods.

Burning of the Amazon forest for grazing lands. Credit: NASA LBA-ECO Project Fire guards insure the survival of remaining forest reserves. Credit Aliança da Terra |

The fourth area is fire control. Fire is perhaps the biggest problem in the Amazon–a lot of people don’t realize this. The further you move away from the equator, the more seasonal the Amazon becomes. Thus the northern and southern parts of the Amazon have a rainy and dry season. The dry season begins now in May and ends in September, when pastures are so dry they are literally matchboxes. Under these conditions, controlled burns of pasture or deforested areas can quickly get out of hand and spread to neighboring natural forest.

Since this is such a critical problem, we hit really hard on fire control. Using satellite imagery, we show the rancher over a period of 5 years how his ranch burned, including how many focal point of fire he had on his property during that time period. We help him create a fire plan, including where he should have fire guards and making sure that he has fire-fighting equipment and communication channels with his neighbors.

Fire is a big concern for Dan Nepstad, IPAM and Woods Hole–every year there are 30,000-40,000 fires in Mato Grosso state alone. The fires burn for 2-3 months–no one puts them out. They burn through virgin forest and the smoke is awful. As a pilot, it is horrendous. You put your life at risk whenever you fly in those conditions.

The more people burn and deforest, the drier the region becomes. The relative humidity is reduced so that forest that once wouldn’t burn now becomes flammable on a yearly basis. Woods Hole thinks it may be approaching the point of no return where you could have much of the Amazon simply go up in smoke. That’s why Dan puts all this emphasis on fire studies in the state.

Aliança da Terra is quite aggressive on this front. Soon we’re going to have a system for sending out flyers and email blasts to help people manage their land to reduce this risk. Right now most people don’t take the proper measures because one they are lazy or don’t know how. The state of corruption doesn’t give them much reason to act. In fact, some landowners are afraid to go to the government because they know they will have to pay bribes to get permits. That’s where Aliança comes in. By joining our system, we cut out that bribery process. It’s safety in numbers since we have so many landowners involved in the network. The corrupt crowd know not to ask anybody in our group for bribes because they they’ll be blasted in the press, lose their jobs, and be humiliated. By ensuring transparency we have people lining up to ask for permits to do things the right way in a region that until now was essentially lawless. However, it must be said that the Brazilian Federal Police, Gov Maggi, and the state wildlife agency head, Marcos Machado, have done a great job combatting the old boy’s network, drastically reducing the corruption. So much so that we consider the state Environmental Secretariat (SEMA) a huge ally and we are working hand in hand with them as partners.

Another aspect we focus on is the continuity between forest reserves. Though the law doesn’t require you to have continuity–you can have a block of forest in the middle of your land that has no value ecologically and still be in compliance–it is crucial for conserving biodiversity and ecological services. So we’re trying to encourage people to leave corridors between ranches. We’ve just launched a pilot program that will strive to maintain 150 miles of corridor between the Xingu and Araguaia watersheds. We have all the landowners there, including Indians, working to make this one big swathe of forest that will serve as the last corridor between the two watersheds. Deforestation has destroyed the rest of the forest.

Mongabay: Once a landowner signs on, how does it work? How do you monitor ranches to be sure they are in compliance?

Helping landowners understand how they can obey the law is one way Aliança da Terra works to reduce deforestation in the Amazon. Credit Aliança da Terra |

Carter:

The first year the rancher is in a grace period. He gets a diagnostics evaluation of his property, which is an environmental x-ray that tells then the good things he’s done and the bad things. Subsequently comes the management plan and the timeline which tells the landowner what to do to recuperate his environmental damage. A visitation is scheduled every 12-15 months to ensure that the landowner has taken the corrective actions under the management plan. This will be done until the property is in compliance. The criteria for kicking a landowner out of the system is still being developed. We’re also creating a third party board that will determine how people stay in the system. It won’t be tied into Aliança in order to maintain the integrity of everything.

Google Earth is one way the public may soon be able to monitor the progress of ranchers in the Amazon. Credit: Google Earth / Aliança da Terra |

Remote monitoring using satellite imagery plays an important role in the program, both from an enforcement standpoint but also for transparency. Within 6 months any web user be able to click on a my ranch and see not only an aerial view of my ranch at 50 meter-resolution, but his management plan, whether I’m completing his tasks on time, and if I’ve done anything illegal. A school kid in England can look at my property and tell his mom that I’m doing the right thing. Of course there are some people who will do the wrong thing, but if you have 70-80 percent doing the right thing it creates this incredibly useful tool to encourage conservation. We take digital satellite photographs of a property, that goes into an azimuth and gives you geographical coordinates which go into that guy’s file. Anybody can go to the exact coordinates with GPS and see the exact azimuth to see what was there a year, 2 years or 5 years ago. The technology creates to an easy way to audit people. If we spot check 10 out of 1000, the other 990 hear about the 10 who got spot checked and say, “Shoot we better do the right thing.” That’s the whole idea. All we need is to get the volume to start influencing the market. We’re almost there. Right now we’re at almost 3 million acres surveyed. We put eyes on targets.

Google has shown an interest in the project. It’s still in the early stages but at some point people may be able to use Google Earth to zoom in on ranches. Our properties would be highlighted on their map.

Mongabay: What can people here in the United States do to help your efforts? You are a Brazilian organization but do you have a U.S. entity?

Carter:

We started as the Brazilian Land Trust, a 501(3)c nonprofit in the United States. From that we evolved to a Brazilian organization because we wanted to nationalize this and make it a Brazilian effort since there’s lots on animosity towards international nonprofits here. You kind of shoot yourself in the foot by being one. I’m one of two Americans on the board, everybody else in Brazilian.

We’re based on donations and we run on a very strict budget with almost no overhead. Most of the money goes straight to the field. I wear myself thin out in the field and don’t have much time to fund raise, so we’re always a day late and a dollar short. I do this pro-bono. Anyway we are actively looking for donations. Americans can do so through our web site. We still have a 501(3)c entity so any donations are tax-deductible.

Aliança da Terra’s certifcation label |

Soon the best way to help will be through your pocketbook. The whole point of this program is to reward landowners for their stewardship. Consumers can do this through their pocketbook by purchasing certified products. By supporting a landowner in the Amazon consumers are supporting conservation of the rainforest. Consumers can also lobby large corporations and distributors to source their products to groups like ours.

A year from now our product–meat from our certified slaughterhouse–will be branded in Europe. If the U.S. opens up its market to fresh beef from Brazil, then we will have it in grocery stores there as well. All packaging will have our seal.

This system, which will allow consumers to trace the product back to the property where it was produced, will be the first of its kind on this scale. Buyers will be able to go online to view the history of the property in a series of satellite images up until the present. They’ll be able to read the management plan, see the corrective actions taken by landowners, and be confident that the beef they’re buying is coming from a certified sustainable source. It’s being created as the new model for the world to adopt.

Aliança da Terra research staff |

In three to six months we’ll be launching the online mechanism for monitoring. It will be akin to Google Earth so that users can surf the entire property where the product was produced. You can see the streams, the ranchers X-ray of his ranch that we did, you can see him sustainability management plan, you can see the timeline for taking corrective action to fix his problems, his plan for addressing forest fires. The system is very transparent and we have the best science behind it. Woods Hole and IPAM are excellent partners in the process. We love working with them!

Visit Aliança da Terra’s web site

Related interviews

|

Dr. Philip Fearnside, Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus, Brazil Global warming could cause catastrophic die-off of Amazon rainforest by 2080 — 10/22/2006 For the Amazon, there is an immense threat looming on the horizon: climate change could well cause most of the Amazon rainforest to disappear by the end of the century. Dr. Philip Fearnside, a Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus, Brazil and one of the most cited scientists on the subject of climate change, understands the threat well. Having spent more than 30 years in Brazil and now recognized as one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest, Fearnside is working to do nothing less than to save this remarkable ecosystem. |

|

William F. Laurance, president of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation Rainforests face myriad of threats says leading Amazon scholar — 10/16/2006 The world’s tropical rainforests are in trouble. Spurred by a global commodity boom and continuing poverty in some of the world’s poorest regions, deforestation rates have increased since the close of the 1990s. The usual threats to forests — agricultural conversion, wildlife poaching, uncontrolled logging, and road construction — could soon be rivaled, and even exceeded, by climate change and rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. |

|

Dr. Daniel Nepstad, Director of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program Amazon rainforest at a tipping point but globalization could help save it — 06/04/2007 The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belém, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges. |

|

Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team Indigenous people are key to rainforest conservation efforts — 10/31/2006 Tropical rainforests house hundreds of thousands of species of plants, many of which hold promise for their compounds which can be used to ward off pests and fight human disease. No one understands the secrets of these plants better than indigenous shamans — medicine men and women — who have developed boundless knowledge of this library of flora for curing everything from foot rot to diabetes. But like the forests themselves, the knowledge of these botanical wizards is fast-disappearing due to deforestation and profound cultural transformation among younger generations. Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon Conservation Team, is working to stop this fate by partnering with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests. Plotkin, a renowned ethnobotanist and accomplished author who was named one of Time Magazine’s environmental “Heroes for the Planet,” has spent parts of the past 25 years living and working with shamans in Latin America. Through his experiences, Plotkin has concluded that conservation and the well-being of indigenous people are intrinsically linked — in forests inhabited by indigenous populations, you can’t have one without the other. |

|

Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden Biodiversity extinction crisis looms says renowned biologist — 03/12/2007 While there is considerable debate over the scale at which biodiversity extinction is occurring, there is little doubt we are presently in an age where species loss is well above the established biological norm. Extinction has certainly occurred in the past, and in fact, it is the fate of all species, but today the rate appears to be at least 100 times the background rate of one species per million per year and may be headed towards a magnitude thousands of times greater. Few people know more about extinction than Dr. Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden. He is the author of hundreds of scientific papers and books, and has an encyclopedic list of achievements and accolades from a lifetime of biological research. These make him one of the world’s preeminent biodiversity experts. He is also extremely worried about the present biodiversity crisis, one that has been termed the sixth great extinction. |