Southern Ocean may not absorb more CO2 emissions

Southern Ocean may not absorb more CO2 emissions

Giant carbon sink is saturated

mongabay.com

May 17, 2007

Climate change has weakened one the Earth’s largest natural carbon ‘sinks’ raising the possibility that increased warming could reduce the capacity of some systems to absorb carbon dioxide, reports a study published this week in the journal Science.

The four-year study by scientists from the University of East Anglia, British Antarctic Survey and the Max-Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry found that an increase in winds over the Southern Ocean has “led to a release of stored CO2 into the atmosphere and is preventing further absorption of the greenhouse gas.” The researchers say the increase in winds has been triggered by rising concentrations of greenhouse gases and ozone depletion.

“This is the first time that we’ve been able to say that climate change itself is responsible for the saturation of the Southern Ocean sink,” said lead author Dr Corinne Le Quéré of University of East Anglia and the British Antarctic Survey. “This is serious.”

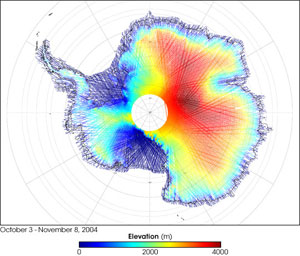

The colors on the map above represent measurements from NASA’s Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite (ICESaa) of Antarctica’s topography, using data collected from October 3 through November 8, 2004. Red shows the highest elevations (up to 4,000 meters above sea level). Yellow, green, and turquoise show progressively lower elevations (green is 2,000 meters above sea level). Dark blue shows sea level. NASA image (top) courtesy Christopher Shuman, ICESat Deputy Project Scientist, Goddard Space Flight Center. |

“All climate models predict that this kind of ‘feedback’ will continue and intensify during this century. The Earth’s carbon sinks — of which the Southern Ocean accounts for 15% — absorb about half of all human carbon emissions. With the Southern Ocean reaching its saturation point more CO2 will stay in our atmosphere.”

The researchers note that since 1981 the Southern Ocean sink has effectively not increased its absorption of carbon dioxide, while global CO2 emissions increased by 40%.

They say their work suggests that stabilization of atmospheric CO2 will be even more difficult to achieve than previously believed. Scientists are concerned that such positive feedback loops between rising carbon dioxide emissions and carbon storage exist in other systems. For example, research published last month in Ecology Letters found that rainforest trees are storing less carbon as atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rise. Similarly, in the Amazon, higher temperatures may result in drier conditions that results in forests losing biomass, sending more carbon into the atmosphere.

The new Science also warns that ocean acidification in the Southern Ocean is “likely to reach dangerous levels earlier than the projected date of 2050.”

“Since the beginning of the industrial revolution the world’s oceans have absorbed about a quarter of the 500 gigatons of carbon emitted into the atmosphere by humans,” said Professor Chris Rapley, Director of British Antarctic Survey. “The possibility that in a warmer world the Southern Ocean — the strongest ocean sink – is weakening is a cause for concern.”

This article is based on a news release from the University of East Anglia