Global warming is killing coral reefs

Global warming is killing coral reefs

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

May 7, 2007

A new study provides further evidence that climate change is adversely affecting coral reefs. While previous studies have linked higher ocean temperatures to coral bleaching events, the new research, published in PLoS Biology, found that climate change may increasing the incidence of disease in Great Barrier Reef corals. Omniously, the research also shows that healthy reefs, with the highest density of corals, are hit the hardest by disease.

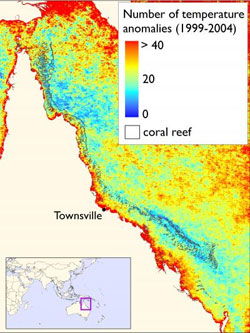

The number of weeks that ocean temperature exceeded its long-term weekly average by more than one degree Celsius between 1999 and 2004. Anomalously warm conditions like these can cause outbreaks of the coral disease white syndrome, contributing to reef decline. Credit: Elizabeth Selig |

Monitoring 48 reefs along more than 900 miles (1,500 kilometers) of Australia’s coastline for six years, a team of researchers led by John Bruno, a marine biologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, tracked white syndrome, an infectious disease that kills coral. They found that “reefs with high coral cover and warm sea surface temperatures had the greatest white syndrome frequency.”

“More diseases are infecting more coral species every year, leading to the global loss of reef-building corals and the decline of other important species dependent on reefs,” said Bruno. “We’ve long suspected climate change is driving disease outbreaks. Our results suggest that warmer temperatures are increasing the severity of disease in the ocean.”

Bruno says that high coral density may facilitate the spread of infection by increasing the number of disease vectors that provide “inroads for infection”. Physical closeness between corals may also make it easier for disease transmission.

White syndrome is a fairly common malady for Great Barrier Reef corals, though it has also had a significant in the Caribbean. Technically a generic name used for a variety of similar diseases, White symdrome manifests as white bands, spots, or patchs on coral. Other research indicates a 20-fold increase in abundance since 2000 on the Great Barrier Reef. |

The findings will help researchers better understand the drivers of coral decline in other areas.

“This study developed valuable methods to pinpoint warm temperature as a partial driver of disease outbreaks. These methods will also be used to study climate drivers of disease outbreaks in other regions of the world,” said Drew Harvell, a Cornell University professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and a co-author of the study.

Scientists have expressed a great deal of concern over the potential impact of climate change on coral reef ecosystems. Both increasingly levels of acidity, which reduce the ability of coral to generate their main structural material, and higher sea temperatures, which can cause “bleaching” or expulsion of the symbiotic algae that enable corals to feed, are cited as the primary risks to reefs in a world of higher atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

Related articles

Some corals may survive acidification caused by rising CO2 levels

(3/29/2007) Several studies have shown that increased atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are acidifying the world’s oceans. This is significant for coral reefs because acidification strips carbonate ions from seawater, making it more difficult for corals to build the calcium carbonate skeletons that serve as their structural basis. Research has shown that many species of coral, as well as other marine microorganisms, fare quite poorly under the increasingly acidic conditions forecast by some models. However, the news may not be bad for all types of corals. A study published in the March 30 issue of the journal Science, suggests that some corals may weather acidification better than others.

Carbon dioxide levels threaten oceans regardless of global warming

(3/8/2007) Rising levels of carbon dioxide will have wide-ranging impacts on the world’s oceans regardless of climate change, reports a study published in the March 9, 2007, issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Increasingly acidic oceans damaging to marine life

(7/5/2006) Carbon dioxide emissions are altering ocean chemistry and putting sea life at risk according to a new report released today. The report, “Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Coral Reefs and Other Marine Calcifiers,” summarizes known effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on marine organisms that produce calcium carbonate skeletal structures, such as corals. Oceans worldwide absorbed approximately 118 billion metric tons of carbon between 1800 and 1994 according to the report, resulting in increased ocean acidity, which reduces the availability of carbonate ions needed for the production of calcium carbonate structures.

Coral reefs decimated by 2050, Great Barrier Reef’s coral 95% dead

(11/17/2005) Australia’s Great Barrier Reef could lose 95 percent of its living coral by 2050 should ocean temperatures increase by the 1.5 degrees Celsius projected by climate scientists. The startling and controversial prediction, made last year in a report commissioned by the World Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Queensland government, is just one of the dire scenarios forecast for reefs in the near future. The degradation and possible disappearance of these ecosystems would have profound socioeconomic ramifications as well as ecological impacts says Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, head of the University of Queensland’s Centre for Marine Studies.

more