Higher temperatures slow tropical tree growth

Higher temperatures slow tropical tree growth, global warming mitigation

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

April 23, 2007

Trees may absorb less carbon, complicating global warming mitigation efforts

Climate change may be reducing growth rates of tropical rainforest trees, a development that could have widespread impacts for biodiversity, forest productivity, and even climate change itself, according to new research published in Ecology Letters.

Analyzing tree growth in 50-hectare forest plots in Panama and Malaysia, a team of researchers led by Harvard University biologist Kenneth Feeley found that tree growth rates have decreased dramatically for the majority of species in two lowland tropical forests over the past couple of decades. The results contradict the hypothesis that elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide levels would boost growth rates of trees in the tropics by speeding plant respiration.

“Global change presents plants with two types of change that might have opposite effects on plant growth,” explained study co-author Dr. S. Joseph Wright, a scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. “Increases in atmospheric CO2 provide more substrate for photosynthesis and might lead to increased growths. Increases in temperature increase respiration rates and might lead to decreased growth, as appears to be the case in our study.”

Slowing growth of tropical trees could complicate efforts to fight global warming through tropical reforestation and conservation |

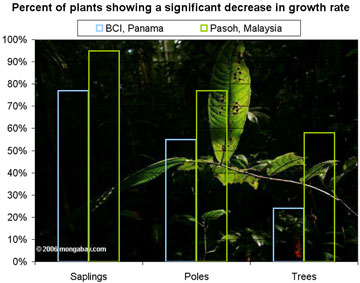

Overall, the researchers measured a significant drop in growth rate for 24 – 71% of species at Barro Colorado Island in Panama, and 58 – 95% of species at Pasoh Forest in Malaysia (depending on the size of stems included in the analyses). Both sites are monitored under a research project by the Center for Tropical Forest Science (CTFS), a partnership between the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the Harvard Arnold Arboretum, the Forestry Research Institute of Malaysia, and some 14 additional institutions that host 50-ha plots. In total, CTFS monitors some 3 million individual trees of more than 6,000 different species at 18 sites around the world.

“I was surprised at the magnitude and at how widespread it was,” Feeley told the Harvard Gazette. “In Malaysia almost every single species was declining in growth. It is very rare that you find anything in these forests consistent across 800 species.”

The results differ from earlier research, based on surveys in the Amazon, which found that large fast-growing canopy trees exhibited higher growth rates possibly in response to rising carbon dioxide levels (Laurance et al. 2004, Lewis et al. 2004). The researchers say that the discrepancy between their findings, which are based on a wider range of species, and those in the Amazon, show that the effects of higher temperatures differ regionally and cannot be generalized for the tropics.

“Our study may indicate that the accelerated tree growth observed at other forests is not indicative of a concerted pantropical response to global environmental changes, but rather that the changes in tropical forest dynamics and structure are driven primarily through regional climate changes such as increased temperature and/or cloudiness,” Feeley told mongabay.com via email.

Wright added that regional temperature change has been variable between the Amazon and other tropical regions.

“We rely on the [Malhi and Wright paper] to show that the Amazon has not yet warmed while Central America and peninsular Malaysia have warmed a lot,” Wright told mongabay.com

In the 2004 Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences paper, Yadvinder Malhi and James Wright reported that most tropical rainforest regions, especially Central America, southeast Asia, and the Congo Basin, have warmed at a faster rate than the Amazon Basin since 1960.

Global implications

The researchers say their results may have significant implications for global biodiversity conservation efforts, tropical forest resource exploitation, and global warming mitigation initiatives that rely on carbon sequestration by trees in tropical regions.

“Tropical forests support the majority of terrestrial animal species, all of which depend either directly or indirectly on plant productivity as a source of energy. Consequently, if decreased stem growth is in fact indicative of an overall decline in net primary productivity, this will reduce the amount of energy available to consumers, in turn reducing the abundance and diversity of animal species that can be supported,” Feeley explained, adding the caveat that “the impact of reduced productivity on animal communities will depend greatly on whether these systems are regulated primarily by bottom-up (i.e., resource availability) or top-down (i.e., predation) pressures.”

Data from the study for Barro Colorado Island, Panama and Pasoh, Malaysia. Saplings have a stem diameter at breast height (dbh), a standard unit of mesaurement in ecology, of 10—50 mm at breast height, poles: 50—100 mm (dbh), and trees: 100 mm (dbh). Growth rate decline occurred in 95-99 percent of plant species, but the decline was significant in the number of species reflected in the chart above.. |

Feeley said that decreased tree growth could further impact the conservation of tropical forests through its effects on human activities.

“Tropical forests are an extremely valuable source of timber. Decreased stem growth may eventually result in reduced standing stocks of timber, he said. “In addition, it will almost certainly slow the rate of forest recovery following logging and thereby increase the rotation times required between successive harvests.”

“In order for loggers to maintain current yields in the face of decreased growth, they will have to increase either the extent and/or intensity of timber extraction. Clearly, more intensive and more widespread logging does not bode well for the conservation of tropical forests since logging may negatively impact diversity either directly or indirectly through fragmentation, edge creation, and synergistic effects such as increased risk of fire.”

Feeley added that a decrease in plant productivity could “necessitate an increase in the intensity of extraction for non-timber products” to unsustainable levels.

Impact on climate change itself

The Ecology Letters study also has implications for global warming mitigation schemes that rely on the planting of trees in the tropics to sequester carbon emissions. Such reforestation initiatives, which promise to conserve biodiversity while helping to fight climate change, have enjoyed wide support from scientists, international development agencies, and governments over the past year.

Since higher temperatures may lead trees to absorb carbon at lower rates, the research suggests that sequestration initiatives would need to conserve and plant larger areas of tropical forest than previously expected to offset rising emissions.

The results further raise the disturbing possibility that the planet could be on the cusp of a cycle that produces ever-higher temperatures.

“If our hypothesis that tropical tree growth rates are decreasing in response to higher temperatures is correct, this creates the danger of positive feedbacks: higher temperatures cause reduced tree growth which in turn results in slower rates of carbon uptake and more deforestation/land conversion, which then results in accelerated increases of atmospheric CO2 and global warming, causing further reductions in growth and so on and so on,” said Feeley.

While this scenario is ominous, Feeley cautions that more research is needed to understand and model the effects of climate change on forests.

“There remains a great deal of uncertainty in the underlying mechanisms as well as the generality of these results. These uncertainties highlight the need for additional long-term large-scale research from other tropical forests.”

CITATION: Kenneth J. Feeley, S. Joseph Wright, M. N. Nur Supardi, Abd Rahman Kassim and Stuart J. Davies. (2007). Decelerating growth in tropical forest trees. Ecology Letters (2007) 10: 1—9 doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01033.x

OTHER REFERENCES: Laurance W.F., Oliveira A.A., Laurance S.G., Condit R., Nascimento H.E.M., Sanchez-Thorin A.C., Lovejoy T.E., Andrade A., D’Angelo S., Ribeiro J.E. & Dick C.W. (2004) Pervasive alteration of tree communities in undisturbed Amazonian forests. Nature, 428, 171-175

Lewis S.L., Phillips O.L., Baker T.R., Lloyd J., Malhi Y., Almeida S., Higuchi N., Laurance W.F., Neill D.A., Silva J.N.M., Terborgh J., Lezama A.T., Martinez R.V., Brown S., Chave J., Kuebler C., Vargas P.N. & Vinceti B. (2004) Concerted changes in tropical forest structure and dynamics: evidence from 50 South American long-term plots. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B, 359, 421-436