Eco-friendly palm oil could help poverty alleviation in Indonesia

Eco-friendly palm oil could help alleviate poverty in Indonesia

Palm oil is not a failure as a biofuel

Rhett A. Butler

mongabay.com editorial

[part 1 | part 2]

April 4, 2007

The Associated Press (AP) recently quoted Marcel Silvius, a renowned climate expert at Wetlands International in the Netherlands, as saying palm oil is a failure as a biofuel. This would be a misleading statement and one that doesn’t help efforts to devise a workable solution to the multitude of issues surrounding the use of palm oil.

While I don’t know the context of Mr. Silvius’s remark (such comments are often taken out of context) and recognize him as an excellent tropical ecologist and writer, his quote as it stands in the AP article makes it easier for critics to dismiss environmental arguments on oil-palm development in Southeast Asia.

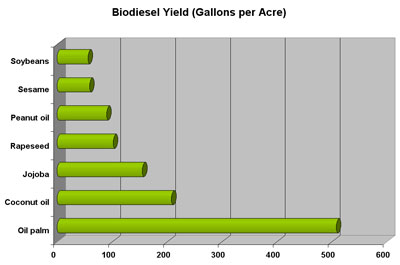

Palm oil is quite obviously not a failure as a biofuel—it is derived from perhaps the most productive energy crop on the planet. A single hectare of oil palm may yield nearly 6,000 liters of crude biodiesel. In comparison, soybeans and corn generate only 446 and 172 liters per hectare, respectively. The problem with palm oil is not its yield, but how it is produced. Presently much of the world’s palm oil is coming out of the forests of Southeast Asia—increasingly in the biodiverse rainforests of Indonesia.

Oil-palm cultivation has expanded in Indonesia from 600,000 hectares in 1985 to more than 6 million hectares by early 2007, and is expected to reach 10 million hectares by 2010. With such rapid growth—and room for expansion—Indonesia is expected to displace Malaysia as the world’s largest producer of palm oil within a few years. Environmental groups say that clearing for oil-palm plantations is directly threatening key habitat for such endangered species as the orangutan, the Bornean Clouded Leopard, and the Sumatran Rhino as well as exacerbating illegal logging already rampant across the region.

Where rainforest once stood in Malaysia now stands row after row of oil palms. Photos by Rhett A. Butler. |

Beyond forest-clearing for oil palm, palm-oil production often employs large amounts of fertilizer and generates hefty amounts of waste, which can pollute local waterways. An added threat comes from the conversion of carbon-rich peatlands for cultivation. Merely draining peatlands releases massive amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere—Silvius’s own Wetlands International [Report: PDF] estimates that destruction of these ecosystems and forests in Indonesia alone releases some 2 billion tons of CO2 per year or 8 percent of total anthropogenic emissions of the greenhouse gas.

So yes, as currently practiced, palm-oil production often has a significantly negative impact on the environment, but it’s unlikely that oil-palm plantation development will slow anytime soon. Its continuing growth is due to (1) lack of economic alternatives in many areas where the renewable energy source is grown and (2) rising biofuel demand from China.

After large-scale deforestation in the lowlands and the importation of millions of people through poorly-executed transmigration programs, there are few economic options in most of Borneo and Sumatra, two islands where much of the current land conversion for oil palm is occurring. Having lost jobs in the forestry sector, many villages are faced with having to decide whether to give up the remaining forest for oil palm or continue with subsistence living. Oil-palm plantations are often viewed as offering the best economic potential, especially given rapidly expanding demand from China.

|

While policymakers debate in Brussels the impact of biofuels, it seems clear that in the future China is going consume far greater amounts of biodiesel than Europe. With demand for cars surging and the country facing energy supply constraints and pollution problems, China appears to be ramping up for a massive expansion of diesel car production. Where is the diesel fuel to power these vehicles going to come from? Smart bets are on oil palm in southeast Asia and soybeans in the Amazon. Why else would state-backed Chinese firms be bankrolling oil-palm development in Indonesia and infrastructure projects linking coastal South America to the heart of the Amazon? The potential of close-to-home oil-palm plantations is simply too alluring.

Offering palm oil producers a carrot

Oil-palm plantations in and around Tanjung Puting National Park in Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo Satellite image courtesy of Google Earth.

Vast areas of natural forest have been converted for soy farms in the Amazon and oil-palm plantations in Asia. However, on a relative basis, oil palm may be more ecologically sound due to its higher oil yield than soy. In theory, because oil palm can produce as much as 30 times more oil per unit of area, it could require less land clearing. Of course, planting oil palm on previously deforested land would be a preferable option. |

Since demand for palm oil isn’t going to go away, Europe’s best approach is to convince Indonesian oil-palm producers to cultivate their crop in a manner that’s less damaging to the environment, as exemplified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). This won’t be done by hand-holding or Kumbaya circles; it will be done through financial incentives—if no one is demanding “green” palm oil, no one will produce it. Europe should inform producers that it is willing to buy a set amount of palm oil (in billions of liters per year), provided that it is independently certified as having been produced in an environmentally friendly and socially equitable way. Europe may even want to offer a minimum price guarantee to satisfy producers that it intends to hold up its side of the bargain.

With scaled-up production and reduced government subsidies (see below), it may turn out that sustainable palm-oil production isn’t as costly as we’ve been led to believe. Further, a guaranteed market for eco-friendly palm oil will provide opportunities for innovation that could further reduce costs.

Europe should engage the Indonesian government as well. It should urge Indonesia to eliminate subsidies for oil-palm plantations grown on natural forest lands, ban development of peatlands, and set aside primary forests for conservation in exchange for funds reflecting the value of the carbon emissions avoided. (Since deforestation produces greenhouse gases, reducing forest clearing cuts global warming emissions.)

Since neither the United States nor China is going to take the lead on this issue, Europe should not miss the opportunity to do so. In a place where there are few economic opportunities for large numbers of rural people living in a degraded landscape, green biofuels could go a long way toward addressing poverty, the environment, and global climate change. Figuring out a way to plant oil palm across the vast stretches of deforested wasteland in Indonesia could be immensely beneficial to local populations as well as the environment—palm-oil plantations sequester more carbon and support vastly more species of wildlife than barren land.

Now’s the time to act. Almost everyone will be better off from greener palm oil.

-

Comment from Marcel Silvius

“Wetlands International is not against palm oil as a biofuel per se, but we have clearly proven that palm oil produced on tropical peatlands is unsustainable and contributes more CO2 to the atmosphere than use of fossil fuels (see our Peat-CO2 report, downloadable from or website). We therefore call for a stop on further palmoil development on peat. As long as there is no worldwide certification system that would identify sustainable palm oil, we are of the opinion that palm oil in general can not be regarded as a suitable (sustainable) biofuel, as already over 25% of all palm oil produced in SE Asia is from peatland areas. Over 50% of new plantations are allocated on peatlands. As such palm oil is a major driver in the further destruction of the remaining peat swamp forests and a significant cause for global CO2 emissions. ”

“We are working with palm oil based industry in the Netherlands to find ways to promote sustainable palm oil production and appropriate certification schemes.”

Related articles

Why is palm oil replacing tropical rainforests? — 4/25/2006

In a word, economics, though deeper analysis of a proposal in Indonesia suggests that oil-palm development might be a cover for something more lucrative: logging. Recently much has been made about the conversion of Asia’s biodiverse rainforests for oil-palm cultivation. Environmental organizations have warned that by eating foods that use palm oil as an ingredient, Western consumers are directly fueling the destruction of orangutan habitat and sensitive ecosystems. So why is it that oil-palm plantations now cover millions of hectares across Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand? Why has oil palm become the world’s number one fruit crop, trouncing its nearest competitor, the humble banana? The answer lies in the crop’s unparalleled productivity. Simply put, oil palm is the most productive oil seed in the world. A single hectare of oil palm may yield 5,000 kilograms of crude oil, or nearly 6,000 liters of crude.

Borneo — 2/22/2007

Borneo, the third largest island in the world, was once covered with dense rainforests. With swampy coastal areas fringed with mangrove forests and a mountainous interior, much of the terrain was virtually impassable and unexplored. Headhunters ruled the remote parts of the island until a century ago. In the 1980s and 1990s Borneo underwent a remarkable transition. Its forests were leveled at a rate unparalleled in human history. Borneo’s rainforests went to industrialized countries like Japan and the United States in the form of garden furniture, paper pulp, and chopsticks. Initially most of the timber was taken from the Malaysian part of the island in the northern states of Sabah and Sarawak. Later, forests in the southern part of Borneo, an area belonging to Indonesia and known as Kalimantan, became the primary source for tropical timber. Today the forests of Borneo are but a shadow of those of legend and those that remain are highly threatened by the emerging biofuels market, specifically, oil palm.

Young orangutan in Borneo. Photo by Rhett Butler |

Saving Orangutans in Borneo — 5/24/2006

The air is warm and heavy with the morning humidity typical of the Borneo rainforest as our kelotok, a traditional boat, motors up a river so black it could be mistaken for ink. The raucous calls of a pair of hornbills can be heard over the rumble of the engine as they fly overhead with their gaudy and over-sized beaks. I scan the surrounding primeval swamp forest for signs of life. Suddenly Thomas cries, "There, in the Nipa palm. An adult male orangutan!" I look up to see a giant red ape casually picking fresh leaves near the top of a riverside palm tree. He watches us before quietly moving back into the forest. This is the first of many wild orangutans we will encounter over the next few days.

Is Indonesia the third largest greenhouse-gas polluter? — 11/3/2006

Is Indonesia the world’s third largest producer of greenhouse gases? A new study by Wetlands International says it is, if the country’s destruction of peat bogs is taken into account. A report released by Wetlands International and Delft Hydraulics, a Dutch research institute, estimates that emissions from Indonesia’s destruction of its extensive peat bogs releases 2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide a year—about 10 percent of world greenhouse gas emissions from human activities. For comparison, the United States, the world’s largest emitter of heat-trapping gases, produces about 7.3 billion tons of greenhouse gases per year.

China invests in $5.5B biofuels project in Borneo, New Guinea — 1/18/2007

China has agreed to invest in a $5.5 billion biofuels project on the islands of New Guinea and Borneo. The plan promises to be controversial among environmentalists who say it will destroy some of the world’s most biodiverse—and threatened— ecosystems.

Borneo governor arrested in rainforest for palm oil fraud — 12/20/2006

The governor of East Kalimantan on the Indonesian part of the island of Borneo has been suspended and faces life in prison for his involvement in an oil-palm plantation scheme that caused the deforestation of a million hectares of tropical rainforest.

Eco-friendly palm oil coming soon, criteria could result in cleaner biofuels — 11/23/2005

Consumers can soon enjoy soap, shampoos, and many other products containing palm oil with a clean conscience, following overwhelmingly acceptance by the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)—a group of producers, buyers, retailers, financial institutions and NGOs—on a set of criteria for the responsible production of palm oil.

Malaysia to build palm-oil biodiesel plants to counter high oil price — 9/26/2005

According to the AFP, Malaysia announced that it will build three plants to produce biodiesel from palm oil, as part of efforts to reduce its dependency on foreign oil and increase demand for domestically produced palm oil.