Overfishing of sharks causes shellfish decline

Overfishing of sharks causes shellfish decline

mongabay.com

March 29, 2007

Overfishing of large sharks is reducing the abundance of shellfish reports a study published in the March 30 issue of the journal Science.

A team of Canadian and American biologists has found that population declines in large predatory shark species — including bull, great white, dusky, and hammerhead sharks — due to overfishing has led to a boom in their ray, skate, and small shark prey species along the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Now these smaller species are depleting commercially important shellfish.

“With fewer sharks around, the species they prey upon — like cownose rays — have increased in numbers, and in turn, hordes of cownose rays dining on bay scallops, have wiped the scallops out,” said co-author Julia Baum of Dalhousie.

“This ecological event is having a large impact on local communities that depend so much on healthy fisheries,” said Charles Peterson, a professor of marine sciences biology and ecology at the Institute of Marine Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and co-leader of the study.

Blue shark photo by Greg Skomal (sanctuaries.noaa.gov). |

Examining research surveys from 1970-2005, the authors found a sharp declines in many shark populations, including a possible 97 drop in scalloped hammerhead and tiger sharks, and more than a 99 percent fall in bull, dusky, and smooth hammerhead sharks.

“Large sharks have been functionally eliminated from the east coast of the U.S., meaning that they can no longer perform their ecosystem role as top predators,” explained Baum. “The extent of the declines shouldn’t be a surprise considering how heavily large sharks have been fished in recent decades to meet the growing worldwide demand for shark fins and meat.”

Worldwide, 26 million to 73 million sharks are killed each year for their fins estimated a 2006 study published in Ecology Letters, while research published last December in the journal Current Biology said that overfishing is causing a population collapse on Australia’s Barrier Reef, generally considered one of the world’s healthier marine ecosystems. Shark fin is a popular delicacy in Asia — especially China, where it is typically served in shark fin soup weddings, business dinners, and other celebrations. Shark fin soup can fetch up to $120 per bowl. Fins are usually sliced off as the shark, often while still alive, which is then thrown back into the ocean.

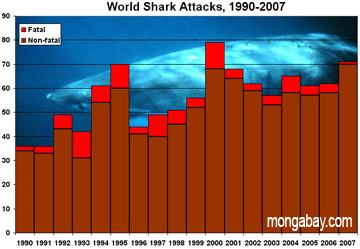

While most people think of sharks as dangerous animals, shark attacks are exceedingly rare. The annual survey of shark attacks, released two weeks ago, showed that it is far more likely to be killed by a falling coconut than a shark. Globally, four people were killed in unprovoked shark attacks in 2006. |

0329shark_1024

In the coastal Atlantic, the decline in large shark populations has triggered an explosion in rays and smaller sharks. The researchers say that the east coast cownose ray population may now number as many as 40 million. These species are voracious predators of bay scallops, oysters, soft-shell and hard clams, they add.

“Increased predation by cownose rays also may inhibit recovery of oysters and clams from the effects of overexploitation, disease, habitat destruction, and pollution, which already have depressed these species,” said Peterson.

“Our study provides evidence that the loss of great sharks triggers changes that cascade throughout coastal food webs,” says Baum. “Solutions include enhancing protection of great sharks by substantially reducing fishing pressure on all of these species and enforcing bans on shark finning both in national waters and on the high seas.”

“Maintaining the populations of top predators is critical for sustaining healthy oceanic ecosystems,” says Peterson. “Despite the vastness of the oceans, its organisms are interconnected, meaning that changes at one level have implications several steps removed. Through our work, the ocean is not so unfathomable, and we know better now why sharks matter.”

Renowned fisheries biologist Ransom Myers at Dalhousie University was co-lead author of the article.

UPDATE: Ransom A. Myers, lead author of the study and a fisheries biologist whose work brought global attention to collapsing fish stocks, died on Tuesday in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He was 54. Myers had been suffering from glioblastoma multiforme, a brain cancer, since last fall, according to Dalhousie University. He is survived by his wife Rita Myers, and five children, Emily, Rosemary, Sophia, Carlo and Gioia

CITATION: Cascading Effects of the Loss of Apex Predatory Sharks from a Coastal Ocean

Ransom A. Myers,1 Julia K. Baum, Travis D. Shepherd,

Sean P. Powers,2 Charles H. Peterson (2007).

This article uses quotes and information from a University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science news release and previous mongabay.com articles.