Global warming will cause local climates to shift and disappear

Climate change will increase extinction risk, especially in the tropics

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

March 26, 2007

Many of the world’s local climates could be radically changed if global warming trends continue, reports a new study published in the early online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors warn that current climates may shift and disappear, increasing the risk of biodiversity extinction and other ecological changes.

John (“Jack”) Williams and John E. Kutzbach of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, together with Stephen T. Jackson of the University of Wyoming, used climate models and greenhouse gas emission scenarios from the recent assessment by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to forecast differences between climate zones today and in the year 2100. They found that under both high and low emissions scenarios, many regions would experience biome-level changes, suggesting areas that may presently feature rainforest, tundra, or desert may no longer have the same type of vegetation in the year 2100 due to climate shifts.

“By the end of the 21st century, large portions of the Earth’s surface may experience climates not found at present, and some 20th-century climates may disappear,” write the authors. “The combination of high CO2 concentrations, still-extensive ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, and current orbital and land—ocean configurations are geologically unprecedented.”

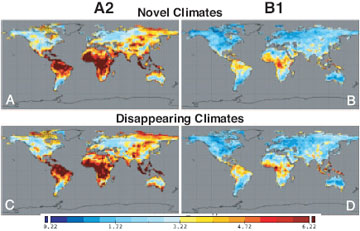

Novel and disappearing climates under a high emissions scenario (A2) and a low emissions scenario (B1). Most of the change occurs in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin American rainforests of the Amazon and Central America.

|

Noting that CO2 concentrations, at 380 parts-per-million (ppm), are already at the highest levels in at least 650,000 years and are projected to increase to 540-970 ppm by 2100, the authors say that the anticipated 1.4 to 5.8 degree C rise of global mean temperatures by the end of the century will likely cause significant climate and ecological shifts in some of the world’s most populated areas — including the southeastern United States, southeast Asia and parts of Africa — and some of the planet’s most biodiverse regions, such as the Amazonian rainforest, and African and South American mountain ranges.

“Novel climates are strongly concentrated in tropical and subtropical regions, with the highest dissimilarities over the Amazonian and Indonesian rainforests,” they write. “Novel 21st century climates are also projected for the western Sahara, low-lying portions of east Africa, eastern Arabian Peninsula, southeastern U.S., eastern India, southeast Asia, and northwestern Australia.”

“Disappearing climates are primarily concentrated in tropical mountains and the poleward sides of continents,” they continue. “Specific areas include the Columbian and Peruvian Andes, Central America, African Rift Mountains, the Zambian and Angolan Highlands, the Cape Province of South Africa, southeast Australia, portions of the Himalayas, the Indonesian and Philippine Archipelagos, and some circum-Arctic regions.”

In total, their models suggest that under a high emissions scenario, 12—39% and 10—48% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface may respectively experience “novel” (i.e. previously unrecorded) and disappearing climates by 2100. Under lower-end scenarios, where emissions of heat-trapping gases are mitigated, the researchers still predict 4—20% and 4—20% change of world land area.

The researchers say their work indicates that future climate change portends elevated risk for biodiversity, especially in the tropics where species have smaller ranges and are less accustomed to fluctuations in temperature and precipitation levels. They cite the Amazon rainforest as being vulnerable to climate change due to “particular risk for increased fire frequency and loss of forest cover.”

Biodiversity conservation will be increasingly difficult

The authors say that conservation efforts in the future will be complicated by a large number of unknowns including the severity of climate change and the response of individual species of climate shifts.

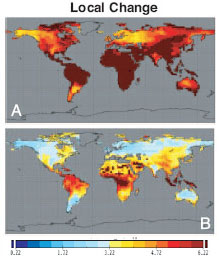

Local change between now and 2100 under two emissions scenarios |

“Forecasting species-level responses to novel climates is a serious challenge… the potential for ecological surprises in the tropics adds urgency to current conservation efforts,” they write. “Disappearing climates increase the likelihood of species extinctions and community disruption for species endemic to particular climatic regimes, with the largest impacts projected for poleward and tropical montane regions,” write Williams and colleagues, adding that biodiversity hotspots — like those in Andes, Mesoamerica, southern and eastern Africa, Himalayas, Philippines, and Wallacea (Indonesia) — are at particular risk from disappearing and shifting climate.

They further note that global biodiversity is not only threatened by climate change, but also by increasing habitat loss, higher levels of exploitation, and growing impact from invasive species.

“Climate change is just one of many current ecological stressors,” they write. “These factors, together with the projected development of novel climates and the threat that the climates particular to some biodiversity hotspots may disappear globally, create the strong likelihood that many future species associations and landscapes will lack modern analogs and that many current species and associations will be disrupted or disappear entirely.”

“We are in for some ecological surprises,” concluded Williams.

Related articles

Impact of global warming on extinction debated

Extinction is a hotly debated, but poorly understood topic in science. The same goes for climate change. When scientists try to forecast the impact of global change on future biodiversity levels, the results are contentious, to say the least.

While some argue that species have managed to survive worse climate change in the past and that current threats to biodiversity are overstated, many biologists say the impacts of climate change and resulting shifts in rainfall, temperature, sea levels, ecosystem composition, and food availability will have significant effects on global species richness.

Biodiversity extinction crisis looms says renowned biologist. While there is considerable debate over the scale at which biodiversity extinction is occurring, there is little doubt we are presently in an age where species loss is well above the established biological norm. Extinction has certainly occurred in the past, and in fact, it is the fate of all species, but today the rate appears to be at least 100 times the background rate of one species per million per year and may be headed towards a magnitude thousands of times greater. Few people know more about extinction than Dr. Peter Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Garden. He is the author of hundreds of scientific papers and books, and has an encyclopedic list of achievements and accolades from a lifetime of biological research. These make him one of the world’s preeminent biodiversity experts. He is also extremely worried about the present biodiversity crisis, one that has been termed the sixth great extinction.

Climate change will worsen species extinction in South America. The combination of rising levels of carbon dioxide and increasing deforestation could reduce biodiversity in the tropical forests of Northern South America, reports a study published in the current edition of the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography. Modeling future ecosystem structure, distribution of precipitation, and land use, Dr. Paul A. T. Higgins says the conditions currently favorable for species richness in the Guiana Shield region of South America, one of the world’s most biodiverse areas, disappear as CO2 levels rise and shift rainfall patterns. In the absence of land-use change, this loss would likely be offset by increasingly favorable climate conditions in eastern Brazil — currently a dry region. However, notes Higgins, widespread modification of ecosystems in Eastern Brazil precludes this development, producing an overall net reduction in biological richness in the region.

CITATION: John W. Williams, Stephen T. Jackson, and John E. Kutzbach (2007). Projected distributions of novel and disappearing climates by 2100 AD. PNAS Early Edition for the week of March 26, 2007. www.pnas.orgcgidoi10.1073pnas.0606292104