Newly tapped Alaska energy source could potentially replace oil

Newly tapped Alaska energy source could potentially replace oil

mongabay.com

February 22, 2007

Researchers in Alaska have successfully drilled gas hydrates — frozen methane deposits that could someday replace petroleum as a key energy source.

The drilling, sponsored by the U.S. Energy Department, was conducted by BP near its Milne Point well. The oil giant found two separate layers of gas containing ice and sent samples to the lab for analysis. The drilling project cost $4.6 million.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, anywhere from 100,000 to 300 million trillion cubic feet of methane exists globally in hydrate deposits. Perhaps 200,000 trillion cubic feet of these lie within U.S. coastal waters — enough potential energy to fuel the country for centuries. While this may seem like great news for domestic energy security, use of these icy methane deposits is currently fraught with problems, including inaccessibility, technical issues with handling the hydrates, and environmental concerns.

Gas hydrates, which are only stable only under low temperature and relatively high pressure, are usually at the bottom of the ocean and in terrestrial permafrost. Bringing these solid methane ice deposits to the surface is difficult without them melting into methane gas.

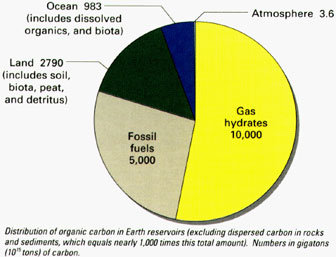

Hydrates store immense amounts of methane, with major implications for energy resources and climate, but the natural controls on hydrates and their impacts on the environment are very poorly understood. Gas hydrates occur abundantly in nature, both in Arctic regions and in marine sediments. Gas hydrate is a crystalline solid consisting of gas molecules, usually methane, each surrounded by a cage of water molecules. It looks very much like water ice. Methane hydrate is stable in ocean floor sediments at water depths greater than 300 meters, and where it occurs, it is known to cement loose sediments in a surface layer several hundred meters thick. The worldwide amounts of carbon bound in gas hydrates is conservatively estimated to total twice the amount of carbon to be found in all known fossil fuels on Earth. This estimate is made with minimal information from U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and other studies. Extraction of methane from hydrates could provide an enormous energy and petroleum feedstock resource. Additionally, conventional gas resources appear to be trapped beneath methane hydrate layers in ocean sediments. IMAGE AND CAPTION TEXT COURTESY OF USGS |

Another problem is the climate implications. In the atmosphere, methane is 21 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas. The exploitation of methane hydrate deposits could further drive global warming through carbon dioxide emissions resulting from increased burning of the fossil fuel as well as direct releases of the gas into the atmosphere.

Scientists say hydrate deposits may have played an important role in past climate change by causing fluctuations in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. One hypothesis, called the “Clathrate Gun” hypothesis, developed by James Kennett, professor of geological sciences at the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB) proposes that past climate shifts were caused by a massive decomposition of the marine methane hydrate deposits.

The rapid decomposition of frozen methane hydrate deposits, possibly a result of higher ocean temperatures, may have been responsible for the sharp spike in atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases during the Palaeocene/Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) — a period of rapid, extreme global warming about 55 million years ago. The methane released during melting would have reacted with oxygen to produce huge amounts of carbon dioxide, also a potent greenhouse gas. The warming caused a mass extinction among marine animals and helped usher in the “Age of Mammals.”

“The destabilization of gas hydrates is likely to be a serious hazard in the near future due to the effects of global warming,” warned Dr. Mark Maslin, a geographer at University College London and a senior researcher for the London Environmental Change Research Center, in a paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Royal Geographical Society last year. “Research already exists to suggest that the release of hydrates increased global temperature 18,000 years ago, and we now face a similar threat as our global temperature continues to rise.”

This article uses information from past mongabay.com posts.