Hotspot conservation will not protect global biodiversity

Hotspot conservation will not protect global biodiversity

Rhett Butler, mongabay.com

December 11, 2006

The concept of biological hotspots has served as a fundamental principle guiding conservation efforts over the past generation. A new study, published in the Dec. 15 online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), argues this may be a mistake and that conservation efforts based on hotspots will not effectively preserve biodiversity.

Biodiversity hotspots are geographic areas that contain high levels of species diversity but are threatened with extinction. First identified by British ecologist Dr. Norman Myers in two articles in The Environmentalist (appearing in 1998 and 1990), the principles of biodiversity hotspots have been the basis for conservation efforts by Conservation International (CI) and other leading environmental groups. Today over half of the world’s plant species and 42 percent of all terrestrial vertebrate species are endemic to the world’s 34 biodiversity hotspots according to CI. These hotspots account for more than 60 percent of the world’s known plant, bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species.

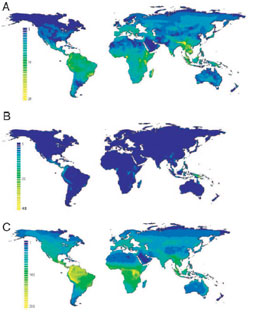

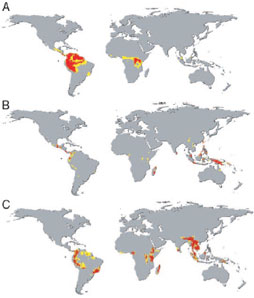

While there’s no doubt that these areas house a significant portion of the planet’s biological diversity, the new PNAS paper argues that the three factors that usually determine hotspots — the number of total species (species richness), the number of unique species (endemism), or the number of species at risk (threat of extinction) — do not necessarily overlap on a global scale. The results raise similar issues to those presented in a paper published in the November 2, 2006 issue of the journal Nature which found a geographical discrepancy in hotspots of endangered species from different groups (i.e. birds, amphibians, mammals) — geographical areas with a high concentration of endangered species from one group do not necessarily have high numbers from other groups.

In the PNAS paper Gerardo Ceballos, a professor of ecology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and Paul R. Ehrlich, a professor of Population Studies at Stanford University analyzed the global distribution of 4,818 species of land mammals and found that there is little overlap or “congruence” among the three types of hotspots. Their findings indicate that only 16 percent of mammalian species are common to all three forms of hotspots.

“Hotspots, which have played a central role in the selection of sites for reserves, require careful re-thinking,” the authors wrote. “Assigning global conservation priorities based on hotspots is at best a limited strategy.”

“We found that if you use species richness as a criterion, you’re not going to protect the endemic or endangered species,” said lead author Gerardo Ceballos. “So the ‘hotspot’ approach, which was extremely valuable in focusing attention on species diversity in the past, has limitations. What’s needed is a more comprehensive analysis that also takes into account the species that live outside the hotspots.”

The authors say that because most of the world’s biodiversity persists in some of the world’s poorest countries where conservation is not a top priority, there is a great need to develop strategies for maintaining biodiversity in human-disturbed landscapes, a discipline known as “countryside biogeography.” Further, say the authors, climate change could well cause species to shift their ranges outside areas that are currently protected.

“The likelihood of species migrations in response to global climate change adds further complexity to the development of conservation strategies, and further limits the present usefulness of the classic hotspot approach,” they wrote.

“Most of the significant habitats that need protecting are outside of hotspots, and we should do a better job managing them properly,” added Ceballos.

Going forward, Ceballos and Ehrlich say that new protected areas should be selected based on more comprehensive criteria.

“Hotspots have value for conservation but they are quite limited,” Ceballos told mongabay.com via email. “Today we can do better evaluations to determine priority sites for conservation at the world level. Such analyses indicate a more complex scenario than just protecting hotspots. Basically, our suggestion is that new protected areas should be selected because of their concentrations of endemic or endangered species, their complementarity, representation of local populations, and protection of ecosystem services.”

“I proposed three things to try to minimize population and species extinctions,” continued Ceballos, summarizing their work. “One, set aside more protected areas, within and outside hotspots. Two, improve the value of the seminatural matrix (i.e. landscapes dominated by human activities) for biodiversity conservation. Three, try to reduce human population density and poverty.”

Ceballos and Ehrlich added that beyond setting aside additional protected areas and making human-altered habitats more hospitable to biodiversity, efforts to reduce human pressures on biodiversity and remaining ecosystems are key.

“All conservation biologists should be attempting to find ways of reducing the basic drivers of biodiversity loss: population growth, overconsumption by the rich, and the use of faulty technologies and socio-economic-political systems,” they concluded.

This article uses quotes and information from the PNAS paper and a news release from Stanford University.