Species evolution not making up for extinction caused by climate change

Species evolution not making up for extinction caused by climate change

mongabay.com

November 14, 2006

Current global warming has already caused extinctions in the world’s most sensitive habitats and will continue to cause more species to go extinct over the next 50 to 100 years says a new study published in Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics by a University of Texas at Austin biologist. The study, Dr. Camille Parmesan, an associate professor of integrative biology, also showed that species are not evolving fast enough to avoid extinction.

Parmesan’s analysis — based on a review 866 peer-reviewed papers that documented the impact of climate change on species and ecosystems — is the most comprehensive study since 2003 on the effects of climate change on species.

“This is absolutely the most comprehensive synthesis of the impact of climate change on species to date,” said Parmesan. “Earlier synthesis were hampered from drawing broad conclusions by the relative lack of studies. Because there are now so many papers on this subject, we can start pulling together some patterns that we weren’t able to before.”

Parmesan found that the most dramatic impacts of climate change on biodiversity are seen in species restricted to niche habitats and small ranges, like polar regions and mountaintops.

Camille Parmesan, associate professor of integrative biology |

“We are seeing stronger responses in species in areas with very cold-adapted species that have had strong warming trends, like Antarctica and the Arctic,” said Parmesan. “That’s something we expected a few years ago but didn’t quite have the data to compare regions.”

“Some species that are adapted to a wide array of environments—globally common, or what we call weedy or urban species—will be most likely to persist,” said Parmesan. “Rare species that live in fragile or extreme habitats are already being affected, and we expect that to continue.”

Pearson found that amphibians, butterflies, and polar species are particularly as risk, though she noted said that scientists cannot yet predict how organisms will respond to climate change as a group.

“Whether it’s within fish, trees or butterflies, you’re seeing some species responding strongly and some staying fairly stable,” said Parmesan. “But within each group you’re still seeing about half of the species showing a response. It’s a very widespread phenomenon.”

While some species will decline as climate changes, some species will migrate and thrive under new conditions, she says.

“The good news is that some species already had a few individuals that were good at moving, so some populations are evolving better dispersal abilities. These species are able to move faster and better than we thought they could as climate warms at their northern range boundaries. So, they’re expanding into new territories very rapidly.”

Parmesan’s work shows that while some species—especially those with short generation times like insects—are evolving in response to climate change, they are not evolving in ways that could prevent extinction.

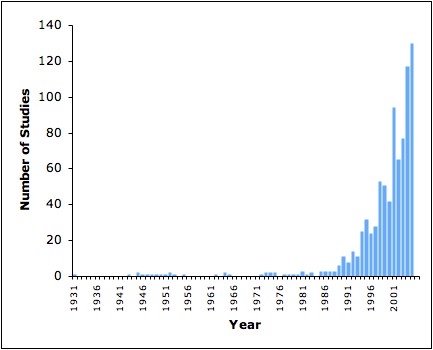

This graph shows an increase in the number of studies finding climate change impacts on wild species or systems taken from Parmesan’s review of 854 papers from 1899 (not shown) to December 2005. |

“Some populations are adapting, but species are not evolving anything that’s really new, something we haven’t been able to say before because we didn’t have enough studies,” Parmesan said. “To really come up with something new that’s going to allow a species to live in a completely new environment takes a million years. It’s not going to happen in a hundred years or even a few hundred years. By then, we might not even think of it as the same species.”

Parmesan’s paper comes as environmental group WWF launched a comprehensive report on the impact of climate change on birds. The report said that species that can easily migrate to new habitats will likely thrive, while birds that live in niche environments may decline.

Recent research has linked historic extinction events with climate change. For example, 250 million years ago, a dramatic spike in temperatures during the Permian period caused 90 to 95% of all marine species, as well as about 70% of all terrestrial species, to become extinct. 55 million years ago, a period of extreme global warming known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) caused another significant extinction event. Scientists say we are in the midst of a sixth mass extinction event — one of our own making — with extinction rates at 100-1,000 times the normal background rate.

This article is based on a news release from the University of Texas at Austin