Energy development threatens Pumalín nature sanctuary in Chile’s Pantagonia

Energy development threatens Pumalín nature sanctuary in Chile’s Pantagonia

Patagonia Under Siege

by George Black, OnEarth Magazine

October 27, 2006

Chile’s booming, energy-hungry economy threatens one of the wildest, most beautiful places on earth.

A global parable

La Paloma. Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

I’m drenched beyond imagining. Sloshing and squelching along the trail, through a steady drip of rain, it’s hard for me to fathom how any place on the planet could be this wet. The coastal rainforest of Chilean Patagonia, cut through by sheer-sided fjords and furious rivers and rimmed with snowcapped volcanoes, glaciers, and vast freshwater ice fields, gets 240 inches — 20 feet! — of rain a year. It’s easy to understand why the Chilean poet Mario Miranda Soussi celebrated the region as La Patagonia de la Tierra y el Agua infinita, despedazada en un torrente de amor, navegando un solo río henchido de milagro: Patagonia of infinite land and water, torn apart by a torrent of love, navigating a single river swollen by miracles.

The Pumalín nature sanctuary, 700,000 acres of dense, primordial green, belongs to a wealthy American named Douglas Tompkins. The biodiversity of the place is staggering. Half the plants here grow nowhere else on the planet. Soaring above the forest canopy are Pumalín’s prized alerce trees, known as “the redwoods of the Andes.” The Linnaean name for the alerce is Fitzroya cupressoides; Charles Darwin named the tree for Robert FitzRoy, captain of the HMS Beagle, when he visited Chile in the 1830s. The alerce can grow as high as 200 feet. Smitten by its light weight, straight grain, and resistance to rot, loggers loved it almost to death. The alerces in Pumalín are some of the last survivors, and the near destruction of the tree is a kind of Chilean morality tale, for this is a country whose economy is based, to an extreme degree, on the extraction of raw materials and the destruction of natural resources.

My guide is Gerardo, who is married to the director of Doug Tompkins’s Pumalín Foundation in the town of Puerto Montt, an hour away by small plane, six hours by the ramshackle ferry that makes the journey each day, though only in the (relatively) dry summer months. Gerardo has been guiding here for 10 years, and the highlight of our time together so far has been the sudden sighting of a reclusive pudú, a miniature deer that stands as high as a terrier, with the face of a bat. It’s the first he’s ever seen.

The deep silence of the forest is broken only by the sound of rain on leaves and the occasional cry of the purple and brown chucao, whose descending call is uncannily like the laughter of a loon — only truncated after the first four notes. Gerardo stops abruptly and crushes a leathery, serrated leaf between finger and thumb — tepa, he says, or Chilean laurel. The leaf gives off a concentrated fragrance that suggests oranges and cinnamon and cloves. It’s not to be confused with the tepú growing next to it, whose intensely copper-red wood is so packed with energy, Gerardo tells me, that you can’t use it in wood stoves; it will explode. Presumably someone made this discovery the hard way.

We’re close to our destination now, the trail turning into a ship’s ladder of tree roots, water streaming over our hands and feet, rain penetrating every crevice of our clothing, until at last we’re standing on a rocky overlook, face-to-face with a thunderous double waterfall, giant tree ferns clinging to the rock face in a perpetual curtain of mist. And the truth is that there are plenty of people in Chile, powerful people, who would stand on this rock, contemplate the torrent, and think, God, what a waste of energy.

A LUST FOR POWER

The country’s largest energy utility, Endesa, recently announced plans to build four giant dams in Chilean Patagonia, a pair on each of the region’s two biggest rivers, the Baker and the Pascua. A heterodox coalition of local residents, environmentalists, energy experts, business leaders, and wealthy landowners (including both Chileans and foreigners such as Doug Tompkins) has already taken shape to oppose the dams, and a great deal rides on the outcome. In a sense, you can think of this fight as a Latin American version of the conflict over drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In both cases, two completely different things are at stake — on one hand the survival of a unique wild ecosystem, on the other the underlying premises of national energy policy.

And the fight to save the rivers of Patagonia is not just a local matter, for what happens in Chile tends to have repercussions throughout the developing world. Chile’s particular misfortune is to have served repeatedly as a laboratory for social experiments of one kind or another. From 1970 to 1973, under President Salvador Allende, it was a cold war battleground, a litmus test of Washington’s tolerance of a democratically elected socialist government. For the next 17 years it endured the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet and his brutal military and secret police. While millions of Chileans experienced the Pinochet era as a nightmarish dystopia, others hailed it as a miracle, a showcase for free-market absolutism that economists around the world soon hurried to emulate. Since 1990, when Pinochet departed the scene, Chile has steadily clawed its way back to democracy, and once again it has played the role of global exemplar — but this time for its peaceful transition from military to civilian rule. In many respects, Chile’s most recent presidential election is the culmination of that process. The new president, who took office in March, is Michelle Bachelet — socialist, feminist, single mother, former political prisoner, torture survivor, and self-proclaimed environmentalist.

Sea Lions. Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

Yet there is an enormous paradox at the heart of Chile’s return to democracy, for no civilian government since Pinochet’s demise (Bachelet’s being the fourth) has dared to tinker much with the radical free-market ideology fostered by the military. The watchword of the Chilean “miracle” has been headlong growth, currently running at about 6 percent a year. Arriving in the capital, Santiago, for the first time in almost 20 years, it was impossible not to be struck by the dizzying array of prestige projects: a gleaming new airport, a sweeping autopista that whisks you past the slums to the city center, a spotless and efficient subway system.

These megaprojects are the high-profile symbols of Chile’s success, their message being that unfettered economic growth and the return to democracy are joined at the hip. But there is a drastic, if as yet invisible, cost. Energy demand is growing even faster than the gross domestic product, and the government says that Chile will need to double its energy production every eight years if its miracle is to be sustained. According to Endesa — once state-owned, then privatized in 1987 under Pinochet, and now part of a larger Spanish corporation — the silver bullet is hydropower. But Endesa’s opponents say the dams on the Baker and the Pascua are only the first step; if the logic of Chile’s current growth model goes unchallenged, then the major rivers of Patagonia will fall like so many dominoes, destroying one of the last truly wild places on the planet. And that, says Doug Tompkins, never a man to mince words, is total insanity.

Esprit, the upscale clothing company that Doug Tompkins owned with his first wife, was the source of his fortune. His second wife, Kris McDivitt, made a fortune of her own as CEO of another clothing empire, Patagonia. Together, the couple now own more than two million acres of land in Chile and Argentina. Pumalín, the first and largest of these holdings, took shape around a dilapidated farm that Tompkins bought in 1991, at the head of a fjord named Reñihue.

There’s no road to the Reñihue farm (now anything but dilapidated); a small launch gets you there, bumping over the rough waters of the fjord. Halfway, the boatman suggests that we detour to take a look at two colonies — rookeries, as they’re called — of sea lions. There are 200 or 300 animals in each, clustered shoulder to shoulder on the rocks above the tide line. The great whiskered bulls lie inert, like rocks themselves, each surrounded by a harem of six or seven cows and a gaggle of nervous pups. As the boat edges closer, outboard throttled way down, the sea lions initiate the opening movement of what turns out to be a four-part encounter. The bulls, bestirring themselves, fill the air with deafening bellows of territorial defense, as a tremor of anxiety ripples through the bodies on the rocks. But then an inquisitive scouting party takes to the water to check out the intruders, while the bulls continue to grunt and grumble among themselves. The scouts seem favorably disposed toward us, for all of a sudden — stage three of the encounter — the water is full of cows and pups, belly flopping off the rocks, nosing their way toward us, dozens of them in a row now, some leaping bodily from the blue-green water like dolphins, until the nearest are no more than 10 or 15 feet from the boat. As with dolphins, there’s a sense of playful curiosity, of testing the limits of our meeting. But eventually the boatman turns to go — Tompkins and McDivitt are expecting us for lunch — and the sea lions set up a doleful wail, uncannily suggestive of a human cry, as if urging us back to their rocks like the selkie of Celtic legend.

This salmon farm south of Puerto Montt is part of a burgeoning industry that now brings Chile about $1.5 billion a year in export earnings. Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

The subject of sea lions makes Doug Tompkins very angry, for they are routinely shot by the salmon farmers whose cages seem to line every fjord in this part of Chile. Tompkins came here originally fired by the dream of a wilderness expanse entirely free of humans, but ideals quickly collided with reality. Salmon farmers were the first of many enemies he made after arriving in Chile with these outlandish notions. For all its surface civility, Chile has deep reserves of unreason, and one interest group after another lined up to demonize Tompkins: Pinochetistas said he wanted to divide the country in two; Catholic Church leaders accused him of being a covert promoter of abortion; the military’s lunatic fringe spread dark rumors of plans for a Zionist enclave (a strange one, that, since Tompkins is a WASP from Dutchess County, New York); Christian Democrats, who were in power when he got here, said he was conspiring to keep out foreign investors (the odd logic of Chile’s open-door policy being presumably that foreigners who want to extract the country’s natural resources are welcome, but those who want to invest their fortunes in conserving them are not).

Part of Tompkins’s problem was that private philanthropy, let alone private conservation initiatives like Pumalín, was all but unknown in Chile; still, Tompkins seemed to think that his good intentions were self-evident, that there was no need to promote them to his hosts. He was wrong about this, and although he has grown more diplomatic over the years, much of the animosity persists. In a speech last year, for instance, the head of the powerful trade association SalmonChile compared Pumalín to Colonia Dignidad, a secretive encampment in southern Chile described by a congressional commission as “a state within a state.” To put the salmon farmer’s remark in its full perspective, bear in mind that Colonia Dignidad was run by a former Nazi and pedophile who allowed Pinochet’s secret intelligence service, the DINA, to use the camp as a torture center.

Tompkins’s environmentalism has always been of the radical variety. Even before he sold Esprit in 1990, walking away with an estimated $150 million, he had become a devotee of the Norwegian deep-ecology theorist Arne Naess, and had set up his own Foundation for Deep Ecology in Sausalito, California, to promote Naess’s ideals: a metaphysical connection to the natural world and a rejection of the idea that humans are in any way superior to other species (this being the part to which the Catholic Church took special exception). Tompkins’s dislike of technology in particular is legendary. Even so, before lunch he gets out his laptop to show us a brief DVD about Pumalín and the couple’s other properties — notably the Estancia Valle Chacabuco, an abandoned, 173,000-acre sheep farm that McDivitt recently bought, several hundred miles south of here, on the banks of the Río Baker.

But the DVD player is uncooperative. Tompkins fiddles ineffectually with the controls.

“Birdie, I’ve got a problem here,” he says, waving a plug in the air.

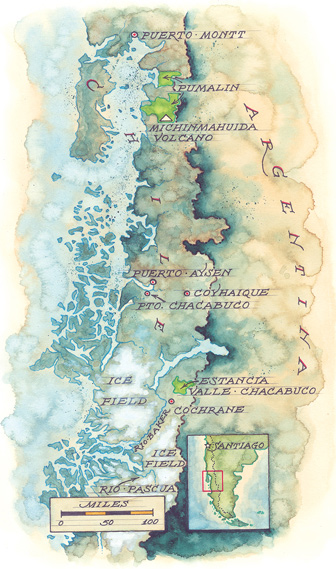

Map by Mike Reagan

|

“Yes, dear.” McDivitt’s voice floats in from the kitchen.

More fiddling. “I goofed up here. Maybe I didn’t put that… I guess I didn’t get the… I need a tech weenie.”

Eventually New Age music starts up and the screen fills with images of rainforest. But just as quickly it goes blank again, and Tompkins says, “Aargh. Birdie!”

McDivitt finally appears from the kitchen, wiping her hands on her apron, looking capable. “Step aside, gentlemen,” she says. “Let somebody who really knows what they’re doing take care of this.” You get the sense this kind of exchange must be a regular feature of the marriage.

Later, over lunch, as Tompkins wolfs down prodigious handfuls of intensely flavored blueberries from the Reñihue farm, his one-man war on technology rages on. Things like the DVD and the laptop, he says, “are just an intermediate tool. It’s a matter of fighting fire with fire — temporarily. But you can’t use technology without giving power to the transnationals, and they’re ruining the world. It’s gotta go. Get these things and you get the transnationals, the military, the whole industrial enchilada. In an agrarian society you don’t need any of this.”

Cutting a slice of homemade marzipan cake, the unflappable McDivitt says, “This new iPod of mine, it’s amazing. I’ve even started downloading whole books. I just downloaded Thoreau.”

Tompkins freezes in mid-mouthful, a stricken expression on his face. “That’s terrible.”

“Yeah, yeah,” McDivitt sighs, rolling her eyes. “You always pooh-pooh all my new technology.” A beat. “Until you steal it.”

When lunch is cleared away, Tompkins suggests we go up in his Cessna for a tour of Pumalín and the small organic farming projects that are dotted around the fjords. On the way to the grass airstrip, I can’t resist asking him whether he uses GPS in the plane. He’s visibly put out by the trick question. “Well, yeah,” he finally says grouchily. After another pause he adds, with a certain amount of defiance, “But it makes me a worse pilot.”

To the nervous flier, there seems to be nothing wrong with Tompkins’s piloting skills as he threads the Cessna between scree slopes and vertical waterfalls and fragments of glacier and the abbreviated snow cone of the 8,000-foot Michinmahuida volcano — his own personal volcano, according to the property lines — and then comes in low over one of the model farms.

“Coming here 16 years ago I was no farmer,” he says, suddenly in a more reflective mood. “We came here and bought up all these broken-down farms. The previous owners had trashed them worse than you can imagine. No management whatsoever. The most crass and unsophisticated agricultural practices you’ve ever seen. Probably this was what Ohio looked like in the 1840s. No chain saws; they just burned it.”

A few miles to the north, he banks the plane steeply so I can get a good look at the tethered cages of the salmon farms that line the Fjordo Comau. “One thing craps out, they try another,” he growls. “Damned salmon farms are the latest.” A few minutes later we fly over the model farm at Pillán. Down by the quayside, there are piles of wreckage from the shoreline portion of an abandoned salmon farm, twisted girders and cracked concrete floors, the gutted carcass of a tractor. “Look at that mess. The roof blew off,” Tompkins says. “They crapped up the bottom of the fjord.” Like most salmon farms, he might have added. The seafloor beneath salmon cages quickly becomes a dead zone, carpeted in a deep slime of feces and unconsumed protein from feed pellets, resulting in toxic algae blooms and red tides. The profligate use of antibiotics to ward off disease in the overcrowded pens has led to an increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria. And the whole enterprise is fed by the depletion of humbler parts of the marine food chain. A recent World Bank study found that it takes three to five pounds of fish meal to produce one pound of salmon.

Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

Yet salmon farming is one of the crown jewels of Chile’s economic boom, and its competitive advantage on the world market is based largely on the claim that the fish are raised in “the world’s purest cold waters.” In 1987, the World Bank says, Chile accounted for just 1.5 percent of the global market in farmed salmon. Since then, with its lax environmental laws and cheap labor, Chile has been the beneficiary of tighter regulations in Norway and British Columbia and the complete ban on the industry in Alaska as a result of protests from commercial fishermen who saw a threat to their livelihood. Today, Chile has a 35 percent share of the world market, placing it in a virtual tie with Norway, the industry pioneer. Half the salmon consumed in the United States began life in a cage in a Chilean fjord.

Until recently, most of the salmon farms have been located in Chile’s Xth Region, just north of here. But those waters have pretty much exhausted their carrying capacity, and the salmoneros are now on the march in the XIth Region, which occupies the northern half of Chilean Patagonia. Chile’s salmon farmers and corporations from Japan, Spain, and Norway plan to invest another $800 million here in the next six to eight years, much of it in waters that are part of national parks and reserves. “Salmon farms are taking over every inch of Chile’s coast,” says Ari Hershowitz, director of the Latin American programs at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). “All you need to do is ask for a license and throw down a cage to save your spot.”

About a year ago, Doug Tompkins got a surprise invitation to address a convention of salmoneros in Puerto Montt. “Listen, I told them, this whole process is insane. You purse-seine the seafloor, then you grind it into fish meal, you ship it from the north of Chile to the south, then you feed it to the salmon, then you truck the salmon back onshore, then you pack them up and ship them to Japan. Insane!”

“How did people respond?” I ask. He thinks about it, then brightens, in another of his mercurial mood shifts. “Well, there are guys sitting there in the front row nodding away and saying, God, yeah, the system doesn’t make sense in the long run. They’re like any other group; there are reasonable people.”

THE HORSE ON THE ROOF

With his large ideals, uncompromising rhetoric, and overscale personality, Doug Tompkins has remodeled Chile’s environmental debate with the crude force of a hand grenade. The country’s newspapers love this, and whenever a fight is brewing in Patagonia, the headlines write themselves: Tompkins denounces… Tompkins accuses… Tompkins declares war on Endesa…

That’s how the fight to save the Baker and the Pascua has been depicted, but the reality is a little more complicated. Local environmentalists wince a bit at Tompkins’s willingness to dance the media minuet, but he sees it as giving them protective cover. “I make some offhand remark,” he says, “get the microphone, make a headline. And that allows the NGOs to come in.” Because McDivitt’s newly acquired property, the Estancia Valle Chacabuco, is directly threatened by the Río Baker dams, the couple can hardly be accused (as they often have been in the past) of poking their nose into an issue that is none of their concern. They’re private landowners. The Baker runs along the edge of their property. They have a direct stake in the outcome. And that has aligned them with some improbable allies, including the salmon industry’s leading political backer and Chile’s wealthiest and most important salmon farmer, who also owns a vast tract of land on the Baker.

Tompkins and McDivitt may grab the headlines, but they are in no sense the leaders of the campaign against Endesa. Many people will tell you that the brains behind it belong to a Chilean architect of German ancestry named Peter Hartmann, who runs the regional office of an environmental group called the Committee for the Defense of Flora and Fauna, or CODEFF, in the pretty town of Coyhaique.

Coyhaique, population 42,000, is the urban hub of the central Patagonian region known as Aysén. The Chilean formula of democracy plus growth is thrust in your face from the moment you touch down at the nearby Balmaceda airport and are greeted by a welcoming banner with larger-than-life photos of grinning men in hard hats toiling away on half-completed roads, airports, bridges, and dams.

Peter Hartmann’s house lies at the end of a switchback dirt road in the hills above the town, at the foot of a towering basalt rock called the Cerro MacKay, named for one of the pioneering British settlers who came to Patagonia early in the last century. We bounce and jolt our way up to the house in Hartmann’s egregiously battered pickup truck, springs and stuffing escaping in all directions from the passenger seat. At one intersection he stops and peers out through the mud-splashed windshield, like a dog sniffing the air. “Now, which way do we go?” This strikes me as an odd question, since he presumably takes this road every day.

Hartmann’s whimsical manner, together with his twinkling green eyes and thick mane of white hair and beard, give him a kind of Gandalf the Grey quality. His house, which he built himself, is made of local stone, sustainably harvested native timber, and coligüe, a Chilean member of the bamboo family. Behind the house, organic gardens and overgrown plots of medicinal herbs stretch away toward the Cerro MacKay. The house even has a grass roof. Hartmann used to keep a horse that liked to graze up there until it disappeared one day; he thinks some neighbors stole it.

But all this back-to-the-land simplicity is a bit misleading. Hartmann turns out to be a shrewd political strategist with an encyclopedic command of factual detail. He came here from Santiago in the early 1980s, a champion mountaineer who was part of the first Chilean expedition to climb the forbidding east face of the Aconcagua glacier. He fell in love with the mountains and forests and rivers of Patagonia, and stayed. In 1984 he coined the phrase Aysén: Reserva de Vida — Life Reserve — and the name has stuck, adopted officially by the Coyhaique city government and ubiquitous on road signs, public buildings, and the bumper stickers plastered on the windows of Hartmann’s pickup.

Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

The Life Reserve concept, he says, is “a vehicle to stimulate citizen engagement,” and it’s been at the core of all the battles he’s waged over the past 20 years, many of them against potent adversaries. He insists that local communities are the essence of the emerging coalition against Endesa’s dams, but their residents are by no means born activists, environmentalists, or defenders of wilderness. Drive around Aysén for a couple of days, he advises, and I’ll see what he means.

It’s clear, as the fjords and rainforests give way to open brown pampas, fields of newly harvested wheat, and herds of grazing cattle, that the idea of pristine wilderness has limited relevance here. This is not Pumalín. Even when the cattle lands give way in turn to the steep-sided glacial valleys of the Río Blanco and the Río La Paloma, appearances are deceptive. These rivers, tinted a deep turquoise by glacial silt, could not look more wild. Black-necked swans glide across the quieter reaches of the Río La Paloma; Patagonian torrent ducks skim back and forth over the stretches of white water. But then around the next corner come three members of a family of huasos — first cousins to the Argentine gaucho — father on the first horse, brother and sister hunched together on a glossy chestnut mare, all three wrapped in faded brown ponchos, with dark, wind-beaten faces. And you see that the slope behind their modest farmhouse is a chaotic latticework of dead trees, the residue of the epic burns that denuded these hillsides when the region was first colonized.

Admiral Robert Simpson, the Englishman who gave his name to the river that runs through Coyhaique, was mourning the destruction of the native forests as early as 1870. “It is lamentable,” he wrote, “to see the wastefulness with which these riches are exploited, which constitute the principal future of the province; for each tree that is used, at least ten are destroyed.” The pace increased dramatically in the 1930s and 1940s, when cattle ranchers were granted vast concessions by the Chilean government. “They needed grass for pasture,” Peter Hartmann had told me, “but they found forests. The government told them that if they wanted free land they had to clear it first. And people weren’t going to do that with an axe, so they set the forests on fire. They burned down almost three million hectares [7.4 million acres], more than half of all the forests in Aysén.” The small, hardscrabble farmers, colonos, who came in the wake of the concessions but were relegated to the higher altitudes and the poorer soils, did much the same. Along the way, in their isolated valleys, they developed their own idiosyncratic culture — self-reliant, deeply conservative, and fiercely protective of their land.

Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

Like most roads in Patagonia, this one leads, via ruts and potholes and a rickety, hand-operated ferry, back to water, to more fjords, to more rivers that tumble from the high snow peaks to the deep blue-green of the Pacific Ocean. At the end of the road are two small port towns, Puerto Aysén and Puerto Chacabuco. They’re dismal places that have recently made the transition from commercial fishing to salmon farming, and the sheltered natural harbor of Puerto Chacabuco is enveloped in the stench of fish meal. Drugs are a problem here. Bored teenagers form gangs and fight one another and the police. Some of them practice a Chileanized version of gangsta rap and dream of escape to the big city, far from the water that has been the lifeblood of these towns — but also their curse.

In 1995 a Canadian mining company called Noranda began sniffing around here, salivating, like Endesa now, over all the untapped hydropower that could be extracted from the rivers that flow into the Fjordo Aysén. The logic, Peter Hartmann pointed out, was very much the same as that of the aluminum industry in the Pacific Northwest during the Depression, when it built giant dams on the Columbia River. Noranda dreamed of building a mammoth aluminum smelter in Aysén, using bauxite ore imported from Australia, Brazil, and Jamaica and powered by two imposing dams on the Río Blanco and the Río Cuervo, with a smaller one on the nearby Río Cóndor. The 434-megawatt dam on the Cuervo would rise 380 feet from the valley floor; the new plant, which the corporation called Alumysa, would produce 440,000 tons of aluminum bars a year. There would be 60 miles of new and upgraded roads, more than 50 miles of power lines, a deep-water port. The foreign investment would total $2.75 billion. There would be jobs for all. The Chilean government touted Alumysa as a project of strategic national importance.

The project would also generate — though this point was not emphasized by Noranda — 60,000 tons of solid waste each year during its 50-year life span, and this turned out to be its Achilles’ heel. Hartmann put together a coalition of 11 local groups — environmental organizations, labor unions, tourism operators, cultural and community groups — to oppose Alumysa. It was a fractious alliance; sometimes the whole business felt like herding cats. Doug Tompkins funded the work for a while, but then stopped.

“Why?” I ask Hartmann.

He chooses his words carefully. “It was bad timing,” he says. “He had to stop all his funding in Chile. He was under a lot of scrutiny from the government. It was very difficult.”

Hartmann soldiered on, worked the media, organized demonstrations, went to Canada to attend one of Noranda’s annual general meetings and buttonhole the company’s shareholders. “They didn’t like that,” he grins. But the trump card was played by the salmon-farming industry, which had its eyes on Puerto Chacabuco as a flagship location. “It was ironic,” Hartmann says. “We knew we needed them, but it took them a long time to get involved. When we criticized the salmoneros, they said we were green fundamentalists opposed to development and jobs. Then when we criticized Alumysa, they said the same thing. But then the salmon farmers started saying that Alumysa were polluters, and Alumysa said the salmon farmers were polluters, and we weren’t green fundamentalists anymore. We were respectable people now!”

Technically, the smelter project isn’t dead. Occasionally you’ll still hear talk of Noranda’s scouting for other locations. But it is, Hartmann says, “in the deep freeze.” Forced to choose, the Chilean government seems to have decided that Alumysa was the bird in the bush; salmon farming is the bird in the hand.

THE SPIRIT OF PATAGONIA

The Alumysa saga convinced Peter Hartmann that alliances of the pure-hearted don’t necessarily get you far; on issues of this magnitude, you need to take your friends where you can find them, understanding their idiosyncracies. It’s a lesson that he has obviously taken to heart as he marshals his forces to block Endesa’s dams on the Baker and the Pascua.

Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

Thanks to Pinochet’s free-market reforms, Endesa obtained the water rights to the two rivers in the waning days of the military regime. “The Chilean water system was unique in the world,” says NRDC’s Ari Hershowitz. “If you had the resources to map it, you could basically own a river on demand.” That changed last year, however, when the law was modified to impose hefty royalty payments, which escalate over time, on owners who leave their water rights unexploited. Patagonia, where Endesa owns the rights to 90 percent of the rivers, was granted a seven-year grace period before these royalties kick in — thus giving the company an excellent incentive to accelerate its dam-building plans.

The four proposed dams on the Baker and the Pascua would be enormous, generating a total of 2,430 megawatts. The estimated cost of the project is $4 billion, $1.5 billion of which will be used to build a transmission line almost 1,000 miles long. Construction is projected to begin in 2008, and the first installation — the 680-megawatt Baker I — will go on line in 2012. Endesa won’t talk about its plans on the record, but a rivers advocate in Santiago, Juan Pablo Orrego, shows me a copy of a Power Point presentation the company has produced, and its message seems pretty clear: This is a patriotic initiative — un proyecto país — in which private profit is a secondary consideration. Dams are the only solution to Chile’s mounting energy crisis, and energy from hydropower is clean energy.

Endesa’s public-relations strategy has run into a speed bump of broad-based public opposition, however. “It’s an extraordinary alliance,” Orrego remarks. “NGOs, big businessmen, local landowners, operators of fishing lodges and tourist businesses, and Doug Tompkins, the deep ecologist.”

“I was very nervous when Tompkins got involved,” Hartmann says. “He gets into a fight with Endesa and the press loves it. But now other big landowners and salmon farmers are also against the project. The involvement of Puchi and Alcalde really changed things.” Enrique Alcalde is a powerful cattle rancher on the Río Baker; Victor Hugo Puchi is the president of AquaChile, a $750 million salmon-farming company, the biggest in the country. More important, perhaps, the Puchi family traces its ancestry to Patagonia’s earliest colonizers. This is not just about money and privilege, in other words; it’s also about roots, about people who have, in Doug Tompkins’s phrase, “a love of the peculiarities and particularities of place.” The coalition opposing Endesa is not called Save Our Rivers, or Protect Our Ecosystems. It’s called Los Defensores del Espíritu de la Patagonia: The Defenders of the Spirit of Patagonia. Thinking of this, I remember the huasos on horseback, in their hidden valley.

Yet the opposition to Endesa is only partly focused on immediate local concerns, like the 23,000 acres that would be flooded, the threat to sensitive ecosystems, the conversion of sleepy Cochrane, population 2,200, into a squalid boomtown. It’s more strategic than that, with much of the argument centered on the likely domino effect of the Baker and Pascua dams, the economic alternatives to hydropower, and the folly of Chile’s current energy policy.

Rodrigo Pizarro, an economist who is close to the new Bachelet government and heads a Santiago-based environmental policy group called Terram, thinks Patagonia has plenty of better options, starting with tourism. “It’s the fastest-growing industry in the world,” he tells me. “Ecotourism is growing rapidly. And that’s going to be the value of Patagonia in the future — the rarity of its virgin temperate rainforest, its free-flowing rivers, its glaciers. Chile’s greatest resource today is copper, but 50 years from now it could be Patagonia. It could be like Costa Rica or New Zealand. What’s their greatest asset? Biodiversity. Why did they film Lord of the Rings in New Zealand? Because New Zealand put its biological heritage at the filmmakers’ disposal. Why would you destroy all that if all you’re doing is postponing a solution to your energy crisis?”

Perhaps the most surprising skeptic is Antonio Horvath, a senator from Chile’s XIth Region and the salmon industry’s most passionate advocate in Santiago. Surprising because Horvath is a political conservative, a onetime ally of the military government, and best known for championing the Carretera Austral, the long ribbon of highway that snakes its way south from Puerto Montt, interrupted by fjords and ferry crossings, all the way down to the remote outpost of Puerto Yungay. There were two reasons for building the highway, and Horvath promoted both. One was to stimulate Patagonia’s economic development; the other was to assuage the geopolitical fears of the Pinochet regime, which fretted about an invasion from neighboring Argentina and needed a way to move troops around in the far south. The highway remains a near obsession with Horvath, and his desire to build a missing 40-mile stretch through Pumalín has put him sharply at odds with Doug Tompkins. But now, together with Puchi the salmon baron, Tompkins and Horvath find themselves, improbably, on the same side of the fence.

Horvath’s crucial insight is that Endesa’s plans jeopardize not only the Baker and the Pascua, but every river in Patagonia. Given Chile’s voracious appetite for energy, the new dams on the Baker and the Pascua are nothing more than a stopgap measure. And the dams in themselves aren’t really the main threat. The bigger problem is the thousand miles of power lines that will carry their energy to the rest of the country. Once those are in place, every beautiful, free-flowing river along the way — the Puelo and the Aysén, the Ibañez and the Cisnes, the Palena and the Futaleufú — is up for grabs, ready to be plugged into the national grid in the blink of an eye. And then what? Patagonia will have ceased to be Patagonia.

“But I’ve seen statements from government officials,” I tell Horvath, “that say if they don’t dam the Baker and the Pascua, the only alternative will be nuclear power.”

“That’s pure blackmail,” he snaps. “Throw a scare into people and get them to say yes to the dams. Alternative energy sources are a much better solution, like small-scale run-of-the-river projects. You can build lots of plants like that very quickly if the political will is there. There are studies that say Chile could get 10,000 megawatts from small, high-altitude facilities. And that’s just hydroelectricity. But geothermal power is another attractive option.” In a country that is basically one long string of volcanoes, he might add.

“And then there’s tidal power,” he continues. “There are places in Aysén where the currents are so strong that they’re not navigable. In Puerto Montt, the tides rise and fall by seven or eight meters. There’s fantastic potential there.”

Much of southern Patagonia is barren and windswept. On the highway 40 miles south of Coyhaique, roadside folk art paints an idealized picture of the rugged settlers who eke out a living here by farming sheep and cattle. Photos: Diane Cook and Len Jenshel |

But as Horvath says, pursuing such visionary ideas is a matter of political will. In Chile as elsewhere, election campaigns don’t specialize in raising (let alone addressing) long-term strategic questions. Politicians don’t prosper by asking whether their country is on a fast train to disaster. Politicians say, energy demand is doubling every eight to ten years. That’s the real world; the rest is for the philosophers and the poets.

“Damming all these rivers is madness,” Rodrigo Pizarro says. “But you can’t really blame Endesa. The problem is the failure of the growth model, of our model of energy consumption.”

But what about Bachelet — will she change that? I asked everyone the same question — Pizarro, Horvath, Tompkins, Hartmann, Juan Pablo Orrego. To a man they shrugged. Too early to tell; and she’s up against so many entrenched interests.

Chile’s problem, says Orrego, is that its economy has always been based on extraction; it has what he calls “a mining mentality” toward its natural resources. Dig up the copper and sell it to the world in highly concentrated form; cut down the native forests, plant pine and eucalyptus, and turn them into wood chips and cellulose; dredge the ocean for fish meal, turn it into salmon, and trash the fjords; and consume extravagant amounts of energy in the process. A centrist technocrat like Pizarro, a radical deep ecologist like Tompkins — both would agree with that basic critique of the Chilean “miracle.”

ORDERED BEAUTY

Doug Tompkins and I are standing by a razor-sharp row of alerce seedlings at Vodudahue, perhaps the most ambitious of all Pumalín’s model farms. Tomorrow the rain will come down again in a daylong torrent, but today the sky is sapphire-blue. Vodudahue means “devil’s corner,” Tompkins says, an allusion to the sheer granite peaks that enclose the narrow strip of green valley. People first came here in the seventeenth century, adventurers looking for the fabled Lost City of the Caesars, a Chilean version of the El Dorado myth. These fields were once carpeted with alerces, but the loggers put an end to that. Now a team of young Chileans is working on a reforestation project that Tompkins calls Alerce 3000. The neat rows of seedlings and the manicured lawns make a disconcerting contrast with the wildness of the surrounding mountains. Nature here is being… well, controlled may not be the right word, but certainly helped along in an orderly and efficient way. “We’re trying to integrate a high degree of beauty here,” Tompkins says, “which is missing from today’s discourse. We see beauty, ordered beauty, in everything we do.” It’s an odd remark for a deep ecologist, a devotee of untamed wilderness, but contradictions seem to me by now to be the essence of the man — as they are, perhaps, for all of us.

We look at the seedlings for a while longer, then I ask, “So what do you think is going to happen with the fight over the Baker?”

He thinks about it for a long time, then pulls a face. “The Baker, that’s a tough one,” he says at last. “Going to be a big fight, a big face-off. There’s no way to call it. But you’ve got to think of this not just as dams, but as a system. No one knows where everything is going. Grow, grow, grow, and explode? Grow, grow, grow, and collapse? All this development, it’s a runaway train. No one’s in control. The environmental movement has to keep beating that drum: What’s the plan here?”

Later, on the way back to the airstrip, we cross a narrow, swaying footbridge over the Estero Troliguán, a fast-moving tributary of the Río Vodudahue. Below us, the creek flows clear, like vodka over ice cubes. Doug Tompkins stops abruptly, grabs my sleeve, and points down at the little river. “Look down there!” he exclaims. “That’s what’s really important. Water!”

Further resources

- PDF version of this article as it appeared in OnEarth Magazine

- Audio slide show of pictures from this article

- OnEarth Magazine

- Natural Resources Defense Council

George Black is OnEarth’s articles editor and the author, most recently, of Casting a Spell: The Bamboo Fly Rod and the American Pursuit of Perfection (Random House). His article, “Patagonia Under Siege”, first appeared as the feature story in the Fall 2006 issue of OnEarth, a publication by the Natural Resources Defense Council, and has been posted with his permission.

This article was made possible by a generous grant from The Larsen Fund.