Tree rings could settle global warming hurricane debate

Tree rings could settle global warming hurricane debate

mongabay.com

September 19, 2006

Scientists have shown that ancient tree rings could help settle the debate as to whether hurricanes are strengthening in intensity due to global warming.

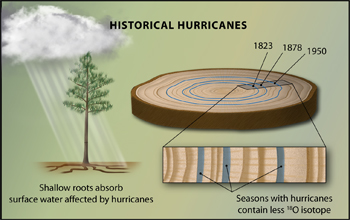

By measuring different isotopes of oxygen present in the rings, Professors Claudia Mora and Henri Grissino-Mayer of the University of Tennessee have identified periods when hurricanes hit areas of the Southeastern United States up to 500 years ago. The research could help create a record of hurricanes that would help researchers understand hurricane frequency and intensity. Currently reliable history for hurricanes only dates back a generation or so. Prior to that, the official hurricane records kept by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Atlantic basin hurricane database (HURDAT) are controversial at best since storm data from more than 20 years ago is not nearly as accurate as current hurricane data due to improvements in tracking technology. The lack of a credible baseline makes it nearly impossible to accurately compare storm frequency and strength over the period.

“Before aircraft and satellite monitoring were available, the Atlantic hurricane data are likely woefully underestimated – except where a hurricane ran directly over a ship or coastal community and there were meteorological observations of pressures and/or winds recorded,” Chris Landsea, a scientist as the NOAA National Hurricane Center, told mongabay.com. “Given that ship captains did their best to NOT sail into the eye of hurricanes, there is a very large underreporting bias in our databases during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, except for hurricanes at landfall along populated coastlines. Disentangling trends due to bias in the hurricane dataset and possible global warming induced changes is then very problematic.”

The shallow roots of the longleaf pine absorb surface water, which is affected by precipitation. Hurricanes produce large amounts of precipitation with a distinctly lower oxygen isotope composition than that in dew or smaller storms. Tracing tree-rings that contain these lower isotope compositions unveils a record of hurricanes that both supports and surpases the present historical record. The current study looks at a 220-year-old record and suggests data up to 400 years can be accessed in future studies. Credit: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation

|

While several studies published since early 2005 have linked recent climate warming to the increasing occurrence and strength of hurricanes over the past thirty years, the research has proved controversial since they relied on potentially flawed data. The new study may help climate researchers re-analyze existing tropical cyclone databases to address these concerns.

“What data we do have – and there certainly are biases in HURDAT that need to be addressed storm by storm – suggest that the middle of the 20th Century was about as busy as the last active 11 years have been (1995 to 2005),” Landsea added. “Disentangling trends due to bias in the hurricane dataset and possible global warming induced changes is then very problematic.”

A press release from the University of Tennessee follows.

University of Tennessee Researchers’ Work Reveals 220-year Hurricane History

New research by two University of Tennessee professors could help us better understand hurricanes by looking to an unusual source: tree rings.

By analyzing the rings of trees in areas that are hit by hurricanes, UT professors Claudia Mora and Henri Grissino-Mayer have found that the oxygen isotope content in a ring will vary if the tree was hit by a hurricane during that year.

Their research is being published in this week’s early online version of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, one of the world’s most cited multidisciplinary scientific journals.

There has been a significant increase in the number of hurricanes hitting the Southeast since the mid-1990s, and scientists have sought to determine the cause for the upswing. Some question exists about whether the increase is part of a regularly occurring cycle of activity, or whether it is being brought about by a cause such as global climate change.

The problem facing this analysis is that the current documented history of hurricane activity in the Southeast dates back only about 100 years — not enough time to establish a cycle that might last many decades at a time.

By looking at older trees, Mora and Grissino-Mayer have been able to create a record of hurricane activity dating back 220 years, more than double the current record.

“We think this can shed light on whether we’re looking at a long-term pattern, or something that could be caused by human activity,” said Mora, professor and head of UT’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

One notable aspect of their research is the accuracy with which the tree- ring oxygen analysis is able to show when a hurricane hit an area. Comparing the tree-ring data to the National Weather Service data over a 50-year period, the tree-ring data showed only one year in which their data reported a hurricane that was not in the list of recorded storms.

The initial data were collected from trees on the campus of Valdosta State University, where Grissino-Mayer was previously a faculty member. The two professors then expanded their research are to swampy nearby Lake Louise, where they were able to find even older trees preserved beneath the waterline.

Different isotopes of oxygen present in the tree rings are the key to knowing whether hurricanes hit the tree. The moisture carried by hurricanes carries a different ratio of oxygen-18 to oxygen-16 than the normal rain that trees absorb. When that moisture falls near a tree, it is absorbed, and that ratio of oxygen is reflected in that year’s ring.

“The level of resolution with this measure is key,” said Grissino-Mayer, a UT associate professor of geography. “Other proxy measures of hurricanes are not able to look at a year-by-year basis.”

Mora and Grissino-Mayer also noted that this opens the door for research to go back even further than 220 years, as older trees are discovered in hurricane-prone areas, perhaps as old as 500 years.

The next steps of their research are already underway. Research teams recently traveled to areas near Pensacola, Fla., and Charleston, S.C., to collect tree samples to analyze, with the hopes of building a broader geographic sample.

Mora and Grissino-Mayer are also working to improve the resolution at which they can examine when the oxygen isotope ratios are different within a tree ring, specifically looking at determining whether storms hit early or late in the hurricane season of the year in which a tree ring grew.

The lead author on the article was UT earth and planetary sciences doctoral student Dana Miller, now a researcher at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, whose dissertation was written about the new findings.

The research was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation, along with the UT President’s Initiative in Teaching, Research and Service.

An abstract of the article, as well as a full-text PDF, are available online at http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/0606549103v1.

RELATED NEWS ARTICLES

|

|

Global warming link to hurricanes challengedChris Landsea, a storm researcher at the National Hurricane Center, and colleagues argued in a paper published in the journal Science that improvements in technology now allow forecasters to produce more accurate estimates of a storm’s power, meaning that more hurricanes are now recognized as Category 4 and 5 storms than prior to the 1980s. They said that the storm databases used by researchers who found links between hurricanes and warmer sea temperatures contain inaccurate information.

Hurricanes getting stronger due to global warming says study Late last month an atmospheric scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology released a study in Nature that found hurricanes have grown significantly more powerful and destructive over the past three decades. Kerry Emanuel, the author of the study, warns that since hurricanes depend on warm water to form and build, global climate change might increase the effect of hurricanes still further in coming years.

Birthplace of hurricanes heating up say NOAA scientists The region of the tropical Atlantic where many hurricanes originate has warmed by several tenths of a degree Celsius over the 20th century, and new climate model simulations suggest that human activity, such as increasing greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, may contribute significantly to this warming. This new finding is one of several conclusions reported in a study by scientists at the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, N.J., published today in the Journal of Climate.

Global Warming Fueled Record 2005 Hurricane Season Conclude Scientists Global warming accounted for around half of the extra hurricane-fueling warmth in the waters of the tropical North Atlantic in 2005, while natural cycles were only a minor factor, according to a new analysis by Kevin Trenberth and Dennis Shea of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The study will appear in the June 27 issue of Geophysical Research Letters, published by the American Geophysical Union.

US denies hurricane link with climate change

Harlan Watson, chief climate control negotiator for the U.S. State Department, told the Associated Press that the Bush administration does not blame global warming or climate change for extreme weather — including the hurricanes that thrashed the Gulf earlier this year.

Hurricane Katrina damage just a dose of what’s to come The kind of devastation seen on the Gulf Coast from Hurricane Katrina may be a small taste of what is to come if emissions of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2 ) are not diminished soon, warns Dr. Ken Caldeira of the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology in his opening remarks at the 7th International Carbon Dioxide Conference in Boulder, Colorado, September 26, 2005.

Hurricane could hit San Diego San Diego has been hit by hurricanes in the past and may be affected by such storms in the future according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). While a hurricane in San Diego would likely produce significantly less damage than Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, it could still exact a high cost to Southern California especially if the region was caught off guard.

Fewer hurricanes predicted for 2006 season William Gray and Philip Klotzbach of the Colorado State University hurricane forecast team issued a report today reducing the number of storms expected to form in the Atlantic basin this season. However, the researchers still call for above-average hurricane activity this year and expect above-average tropical cyclone activity in August and September. That’s despite an average start to the season with two named tropical storms forming in June and July.

2006: Expect another big hurricane year says NOAA The 2006 hurricane season in the north Atlantic region is likely to again be very active, although less so than 2005 when a record-setting 15 hurricanes occurred, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).