Amazon drought extends into second year

Amazon drought extends into second year

mongabay.com

August 11, 2006

The drought in the Amazon rainforest looks to be extending into a second year. Last week Brazil’s government declared a state of emergency across more than 250 towns in the region due to lack of rainfall.

|

Last year’s drought, which left rivers dry, stranded thousands of villagers, and put regional commerce at a standstill, was the worst on record.

A second year of drought is of great concern to researchers studying the Amazon ecosystem. Field studies by the Massachusetts-based Woods Hole Research Center suggest that Amazon forest ecosystems may not withstand more than two consecutive years of drought without starting to break down. Severe drought weakens forest trees and dries leaf litter leaving forests susceptible to land-clearing fires set during the July-October period each year. According to the Woods Hole Research Center, it also puts forest ecosystems at risk of shifting into a savanna-like state.

“Half of the Amazonia’s forests are highly vulnerable to changes in the region’s climate, receiving just enough rainfall to remain green and resistant to fire. Small reductions in rainfall can push these forests tip the balance, make them more susceptible to fire, and impact their role in creating rain clouds,” explains the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon web site. “The risk of fire and drought is enhanced by logging, which opens the forests, and by farmers and ranchers who use fire to replace rainforests with crops and pastures. A brutal downward spiral of drought, forest fire, and further drought could expand across much of the Amazon, replacing the species-rich rainforest with savanna like vegetation. The protection of Amazon wilderness within biological reserves may depend upon preventing this cycle and maintaining forest cover across most of the region.”

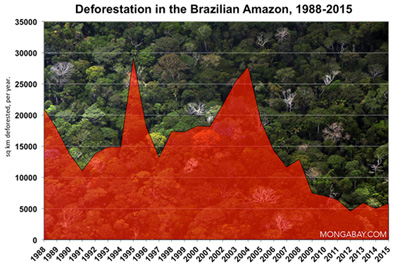

Ongoing deforestation is expected to amplify drought conditions in the region. In March 2006, the journal Nature published a study showing that with current trends in agricultural expansion, 40 percent of the Amazon rainforest could be lost by 2050 while computer simulations by the National Center for Atmospheric Research suggest that deforestation could cause surface temperatures to rise 2°C (3.6°F) or more across the Amazon by 2100, producing a significant drop in precipitation and resulting in a drier climate for the region. Declining precipitation could affect levels of rainfall as far away as Texas.

|

Scientists are not certain as to the cause of the current drought, although warmer water temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean are a leading suspect. Last year some researchers argued that the accumulation of warm waters in the tropical Atlantic helped fuel a record hurricane season while reducing the availability of moisture to the Amazon basin. These conditions are likely to worsen as global temperatures increase.

Some local officials believe deforestation may also be playing a role in the drought. Forest clearing impacts rainfall by disrupting the local water cycle. Under normal conditions, forests add to local humidity through transpiration — the process by which plants release water through their leaves. Moisture is transpired and evaporated into the atmosphere where it contributes to the formation of rain clouds. Scientists estimate that 50-80 percent of the moisture in the central and western Amazon remains in the ecosystem water cycle. However, when forests are cut, as is occurring in Brazil and upper parts of the Amazon watershed in Peru, less moisture is evapotranspired into the atmosphere, resulting in the formation of fewer rain clouds and less rainfall for both the Amazon and neighboring areas.

There is further concern that drought and low water conditions will only worsen in coming years as more forest is cleared and glaciers in the Andes continue to retreat. Glaciers, which are the source for as much as 50% of the water in the upper Amazon, are fast disappearing in Peru. According to a 1997 study by the Peruvian government, the country’s glaciers have shrunk by more than 20% in the past 30 years. Further, the National Commission on Climate Change in Lima projects that Peru will lose all its glaciers below 18,000 feet in elevation in the next decade and possibly all its glaciers within the next 40 years. The impact on the Amazon, when combined with deforestation, could be devastating to the region’s climate, water cycle and economy.

To date, 17-18 percent of the Amazon rainforest has be cleared. In Brazil — which has about one-third of the world’s remaining tropical rainforest cover — over 232,000 square miles (600,000 square kilometers) of rainforest has been lost since 1970.