Recent Coral Bleaching at Great Barrier Reef

By Gretchen Cook-Anderson, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

April 5, 2006

An international team of scientists are working at a rapid pace to study environmental conditions behind the fast-acting and widespread coral bleaching currently plaguing Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. NASA’s satellite data supply scientists with near-real-time sea surface temperature and ocean color data to give them faster than ever insight into the impact coral bleaching can have on global ecology.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is a massive marine habitat system made up of 2,900 reefs spanning over 600 continental islands. Though coral reefs exist around the globe, researchers actually consider this network of reefs to be the center of the world’s marine biodiversity, playing a critical role in human welfare, climate, and economics. Coral reefs are a multi-million dollar recreational destinations, and the Great Barrier Reef is an important part of Australia’s economy.

Scientists use ocean temperatures and ocean “color” as indicators of what is happening with coral. Coral is very temperature sensitive. Ocean “color,” or the concentration of chlorophyll in ocean plants, is important because it informs scientists about changes in the ocean’s biological productivity. NASA satellites capture both temperature and color data from their space-based view of the coral reefs.

Bleaching occurs when warmer than tolerable temperatures force corals to cast out the tiny algae that help the coral thrive and give them their color. Without these algae, the corals turn white and eventually die, if the condition persists for too long.

“Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is the largest and most complex system of reefs in the world, and like so many of the coral reefs in the world’s oceans, it’s in trouble,” said oceanographer Gene Carl Feldman of the Ocean Biology Processing Group at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

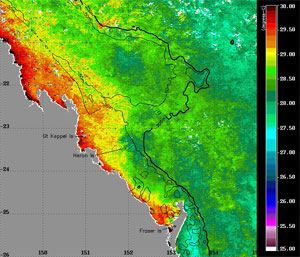

Sea surface temperatures at the southern Great Barrier Reef showing increased temperatures over inshore reefs, the location of the most severe coral bleaching at present. The image was created from the Moderate Imaging Spectroradiometer instrument onboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites. The temperatures range from 25 to 30 degrees Celsius (77 to 86 degrees Fahrenheit) as indicated on the color bar (right). Credit: University of Queensland. CORAL BLEACHING (from mongabay.com) The first coral bleaching event was detected in 1979. Since then, there have been six events, each of which has been progressively more frequent and severe. In the El Niño year of 1998, when tropical sea surface temperatures were the highest yet in recorded history, coral reefs around the world suffered the strongest bleaching on record. 48% of reefs in the Western Indian Ocean suffered bleaching, while 16% of the world’s appeared to have died by the end of 1998. More recently, NASA and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported that during September and October of 2005 while hurricanes battered the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean experienced one of the most devastating coral bleaching events ever recorded. According to scientists in Puerto Rico, the bleaching was both widespread and intense with colonies representing 42 species completely white in many reefs. Surveys showed that 85 to 95 percent of coral colonies were bleached in some areas, while reefs in Grenada suffered close to 70 percent bleaching in some areas. Ove Hoegh-Guldberg of the University of Queensland has warned that Australia’s Great Barrier Reef could lose 95 percent of its living coral by 2050 should ocean temperatures increase by the 1.5 degrees Celsius projected by climate scientists. The combination of higher water temperatures and increased ocean acidity due to high concentrations of dissolved carbon dioxide in the world’s oceans would be the leading factors responsible for such a demise. |

He added, “Coral, which can only live within a very narrow range of environmental conditions, are extremely sensitive to small shifts in the environment. Like the ‘canary in the coalmine,’ coral can provide an early warning of potentially dangerous things to come.”

In 2004, NASA scientists developed a free, Internet-based data distribution system that enables researchers around the globe to customize requests and receive ocean color data and sea surface temperature data captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument aboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, generally within three hours after the satellites pass over the particular region of interest. NASA processes and distributes this data to hundreds of scientists, educators and public officials globally on a daily basis.

Researchers, including Scarla Weeks at the University of Queensland, Australia, are using satellite monitoring to observe changes in sea surface temperatures and ocean primary productivity along the Great Barrier Reef and surrounding waters. Recent dramatic increases in sea surface temperatures are causing a rift in the relationship between corals and the algae that live within their bodies.

“The Great Barrier Reef is an icon, and we just want to know what we can do to save it,” said Weeks. “Sea surface temperatures over the last five months are actually higher in certain locations now than they were in 2002 when we witnessed the worst bleaching incident to date.”

Weeks regularly downloads NASA MODIS data that shows her the extent of and where the coral bleaching is expanding. “We’re not able to do this kind of broad-reaching work without NASA. With this satellite data delivery service, we’re able to observe what’s happening in the ocean in ways we’ve never been able to before,” she said.

According to Weeks, not only does the increased sea surface temperature affect life underneath the water, but it also impacts other marine creatures like sea birds. “After the high sea surface temperatures in 2002 caused the unprecedented bleaching incident, we saw a devastating reproductive failure in sea birds. The adult birds ultimately abandoned their nests resulting in a population loss in an animal vital to the marine ecosystem.

“Rising ocean temperatures are just one of the ever-increasing number of environmental stresses faced by coral reefs in general and the Great Barrier Reef in particular,” said Feldman. “With this distribution service, we’re sharing NASA’s unique ability to monitor our home planet from the vantage point of space and to provide scientists with the best and most timely information to carry out their research.”

This is a modified news release from the National Science Foundation.