China and India Key to Ecological Future of the World, Says Report

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

January 12, 2006

Earth lacks the energy, arable land and water to enable the fast-growing economies of China and India to attain Western levels of resource consumption according to a new report released by the Worldwatch Institute

In its “State of the World 2006” the environmental think tank says China and India, are becoming not only economic powers, but “planetary powers that are shaping the global biosphere” and affecting world economic policies.

“The world’s ecological capacity is simply insufficient to satisfy the ambitions of China, India, Japan, Europe and the United States as well as the aspirations of the rest of the world in a sustainable way,” says the report.

A news release from the Worldwatch Institute can be found below.

State of the World 2006: China and India Hold World in Balance

January 11, 2006

News release from the Worldwatch Institute

The dramatic rise of China and India presents one

of the gravest threats—and greatest opportunities—facing the world

today, says the Worldwatch Institute in its State of the World 2006 report.

The choices these countries make in the next few years will lead the world

either towards a future beset by growing ecological and political instability—or

down a development path based on efficient technologies and better stewardship

of resources.

“Rising demand for energy, food, and raw materials by 2.5 billion Chinese

and Indians is already having ripple effects worldwide,” says Worldwatch

President Christopher Flavin. “Meanwhile, record-shattering consumption

levels in the U.S. and Europe leave little room for this projected Asian growth.” The

resulting global resource squeeze is already evident in riots over rising oil

prices in Indonesia, growing pressure on Brazil’s forests and fisheries,

and the loss of manufacturing jobs in Central America.

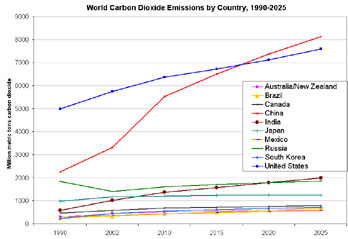

China will overtake the United States in carbon dioxide emissions sometime in the next 15 years. |

The United States still consumes three times as much grain per person as China

and five times as much as India, notes the report. U.S. per-capita carbon dioxide

emissions are six times the Chinese level and 20 times the Indian level. If

China and India were to consume resources and produce pollution at the current

U.S. per-capita level, it would require two planet Earths just to sustain their

two economies.

“We were encouraged to find that a growing number of opinion leaders

in China and India now recognize that the resource-intensive model for economic

growth can’t work in the 21st century,” Flavin said. “Already,

China’s world-leading solar industry provides water heating for 35 million

buildings, and India’s pioneering use of rainwater harvesting brings

clean water to tens of thousands of homes. China and India are positioned to

leapfrog today’s industrial powers and become world leaders in sustainable

energy and agriculture within a decade.”

In 2005, China alone used 26 percent of the world’s steel, 32 percent of the

rice, and 47 percent of the cement. Though their per-capita resource consumption

is still low, with their huge populations China and India are joining the United

States and Europe as ecological superpowers whose demands on the world’s ecosystems

will vastly outstrip those of other countries,according to the report.

The chemical spill on the Songhua River in northern China in November 2005,

which forced a four-day closure of the water system of the city of Harbin,

illustrated the huge environmental challenges facing Asia today. The spill

led to the resignation of China’s top environmental official, Xie Zhenhua,

who authored the foreword to State of the World 2006 shortly before

the disaster. Other challenges facing China and India include:

China has only 8 percent of the world’s fresh water to meet the

needs of 22 percent of the world’s people. In India, urban water demand is

expected to double—and industrial demand to triple—by 2025.

India’s use of oil has doubled since 1992, while China went

from near self-sufficiency in the mid-1990s to the world’s second largest

oil importer in 2004. Chinese and Indian oil companies are now seeking oil

in countries such as Sudan and Venezuela—and both have just started

to build what are slated to be two of the largest automobile industries in

the world.

China and India have the only large coal-dominated energy systems in

the world today—coal provides more than two-thirds of China’s

energy and half of India’s. Both countries are therefore central to

future efforts to slow global climate change: China is already the

world’s second largest emitter of climate-altering carbon dioxide, while

India ranks fourth.

If Chinese per-capita grain consumption were to double to roughly

European levels, China alone would require the equivalent of nearly 40 percent

of today’s global grain harvest. Already, China’s growing imports

of grain, soybeans, and wood products are placing great pressure on

the biodiversity of South America and Southeast Asia.

Such trends have a number of influential Chinese and Indians questioning whether

their countries are on the right path. Zjeng Bijian, Chair of China Economic

Reform, is quoted in the book calling for “a new path of industrialization

based on technology, low consumption of resources, low environmental pollution,

and the optimal allocation of human resources.” Sunita Narain of India’s

Centre for Science and Environment writes in the book’s foreword, “The

South—India, China, and all their neighbors—has no choice but to

reinvent the development trajectory.”

The report notes that China and India are already benefiting from South-South

sharing of ideas,

from biofuels to bus rapid transit systems. Recent commitments by both nations

to develop large wind power and solar energy industries are likely to make

a host of new technologies affordable for poor countries. Their early successful

efforts to employ new approaches include:

In 2005, both nations committed to accelerating the development of new

energy sources. India will seek to increase renewable energy’s

share of its power from 5 percent to 20-25 percent, while China’s ambitious

renewable energy law stands a good chance of jumpstarting wind power, biofuels,

and other new energy options.

Seeking to provide mass mobility to over a billion people without diverting

resources required to meet other human needs, the Chinese Ministry of Construction

recently declared public transport a national priority and is promoting

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT).

In India, where 43 percent of the annual rain and snowfall fails to reach

rivers and aquifers, NGOs have championed water harvesting, using

simple technologies that capture and store water before it can flow away.

In Chennai, the country’s fourth largest city, some 70,000 buildings

harvest rainwater.

In 2004, China implemented automobile fuel economy standards that

are based on European standards and tougher than those in the United States.

China’s commitment to energy efficiency is also reflected in its status

as the world leader in producing and installing compact fluorescent light

bulbs.

Indian officials recently replicated successful small-scalebiodiesel programs

in 100 additional villages in the hopes of bringing revenue to depressed

rural communities while powering local electrical grids and irrigation pumps.

New laws in 2004 gave Chinese non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

stronger legal standing to participate in policy decision-making. There are

now more than 2,000 environmental NGOs in China—a sector that barely

existed as recently as the early 1990s.

The report calls for broader cooperation between China, India, Europe, and

the United States to develop new energy and agricultural systems, maximize

resource efficiency, and continue recent progress towards participatory decision-making

in China and India. Educational and professional exchanges should also be stepped

up. Additionally, it is urgent that China and India be invited into key international

bodies such as the G-8 and the International Energy Agency.

"The rise of China and India is the wake-up call that should prompt people

in the United States and around the world to take seriously the need for strong

commitments to build sustainable economies,” the book concludes. “Viewing

this colossal shift in global geopolitics as an opportunity rather than a challenge

holds the greatest prospect for ensuring a stable and peaceful twenty-first

century.”

STATE OF THE WORLD 2006: Notable Trends

CHINA AND INDIA

India already has the fourth largest wind power industry (p. 11), while

China and India are the third and fourth largest ethanol producers, respectively.

(p. 64) Both countries have vast land areas that contain a large dispersed

and diverse portfolio of renewable energy sources that are attracting foreign

and domestic investment. (p. 11)

The United States, Europe, Japan, India, and China together claim 75 percent

of the Earth’s “biocapacity,” effectively leaving 25 percent

for the rest of the world. (p. 16)

The average person in China has an ecological footprint of 1.6 global hectares,

and, in India, 0.8 global hectares. In contrast, the average person in the

United States has an ecological footprint of 9.7 hectares, and that footprint

grew by 21 percent between 1992 and 2002. (p. 17)

THE GLOBAL MEAT INDUSTRY

Worldwide, an estimated 258 million tons of meat were produced in 2004,

up 2 percent over 2003. Global meat production has increased more than fivefold

since 1950 and more than doubled since the 1970s. (p. 25)

Meat consumption is rising fastest in the developing world, where the average

person now consumes nearly 30 kilograms a year. In industrial countries,

the average person consumes about 80 kilograms of meat a year. (p. 25)

Factory farming is now the fastest growing means of animal production in

the world. Industrial systems today generate 74 percent of the world’s

poultry products, 50 percent of all pork, 43 percent of beef, and 68 percent

of eggs. (p. 26)

FRESHWATER ECOSYSTEMS

Worldwide, half or more of the land in nearly one-third of 106 primary

watersheds has been converted to agriculture or urban-industrial uses. (p.

43)

To support the diets of the additional 1.7 billion people expected to join

the human population by 2030 at today’s average dietary water consumption

would require 2,040 cubic kilometers of water per year—as much as the

annual flow of 24 Nile Rivers. (p. 51)

BIOFUELS

Ethanol and biodiesel together provided 2 percent of global transportation

fuels in 2004. Global production of ethanol has more than doubled since 2000,

while production of biodiesel has expanded nearly threefold. Oil production

has increased only 7 percent since 2000. (p. 61)

Only about 10 percent of the biofuels produced around the world is sold

internationally, and Brazil accounts for approximately half of this. (p.

73)

The world could theoretically harvest enough biomass to satisfy the total

anticipated global demand for transportation fuels by 2050. (p. 74)

The biggest producers—Brazil, the U.S., the European Union, and China—all

plan to more than double their biofuels production within the next 15 years.

(p. 74)

NANOTECHNOLOGY

The value of commercial products incorporating nanotechnology is expected

to reach $2.6 trillion (15 percent of global manufacturing output) by 2014—10

times biotech and as large as the combined informatics and telecom industries.

(p. 79)

More than 720 products containing unregulated and unlabeled nanoscale particles

are commercially available, with thousands more in the pipeline (p. 83),

while the effects of manufactured nanoscale particles on human health and

the environment remain unknown and unpredictable. (p. 79)

MERCURY’S GLOBAL REACH

Coal combustion may provide as much as two-thirds of the 2,000+ recognized

tons of annual anthropogenic emissions of mercury to the atmosphere. (p.

99)

Eighty percent of the mercury used globally is in developing countries,

particularly in East Asia, with 1,032 tons, and South Asia, with 634 tons.

China and India remain responsible for an estimated 50 percent of global

mercury demand. (p. 106)

NATURAL DISASTERS

Overall, economic losses from natural disasters in 2004 totaled $145 billion,

with two-thirds of this attributed to windstorms and the other one-third

to geological events, including the tsunami in South Asia. (p. 118)

A disproportionate number of the world’s poor lie on the frontline

of exposure to disasters: countries with low human development account for

53 percent of recorded deaths from disasters even though they are home to

only 11 percent of the people exposed to natural hazards worldwide. (p. 121)

TRADE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

OECD countries support their farmers to the tune of over $300 billion per

year, and much of that ends up encouraging overuse of chemical inputs and

cultivation on unsuitable land. (p. 145)

The end of 2005 will see nearly 300 regional trade agreements in force.

Most of these agreements, where they are between developing countries, contain

few or no environmental provisions. (p. 149)

GREEN CIVIL SOCIETY IN CHINA

The Tenth Five-Year Plan was China’s “greenest” ever, with

investments to meet environmental objectives set at $85 billion. These targets

were nearly met. (p. 153)

There are now at least 2,000 registered independent environmental NGOs

in China, and more than 200 university green groups are found throughout

the provinces. (p. 157)

TRANSFORMING CORPORATIONS

Today there are more than 69,000 transnational corporations, maintaining

more than 690,000 foreign affiliates. (p. 172)

In 2004, investors filed 327 resolutions regarding social or environmental

issues with U.S. companies—22 percent more than in the previous year.

They subsequently withdrew 81 of these after companies agreed to address

the issues raised, ranging from animal welfare and climate change to political

contributions and global labor standards. (p. 181)

This is a modified new release from the Worldwatch Institute