Army Corps of Engineers lacks plan for restoring coastal wetlands

National Academies’ National Research Council news release

November 9, 2005

-

The Army Corps of Engineers and the state of Louisiana lack an overall plan for restoring coastal wetlands, says a new report from the National Academy of Sciences.

WASHINGTON — Most of the individual projects in a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposal to reduce losses of coastal wetlands in Louisiana are scientifically sound, but taken together they do not represent the type of integrated, large-scale effort needed for such a massive undertaking, says a new report from the National Academies’ National Research Council. An explicit map of the desired future landscape of coastal Louisiana should be developed as soon as possible to guide the selection of more-integrated restoration projects in the future, said the committee that wrote the report.

“Federal, state, and local officials, with the public’s involvement, need to take a broader look at where land in coastal Louisiana should and can be restored, and at how some of the sediment-rich water of the Mississippi River should flow to achieve that,” said committee chair Robert G. Dean, professor of civil and coastal engineering, University of Florida, Gainesville.

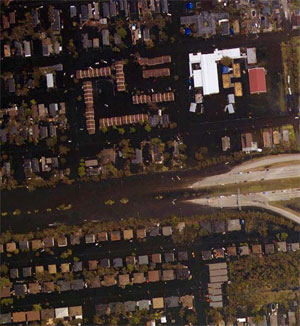

Natural processes and human efforts to tame the Mississippi River with dams, levees, and other artificial barriers have reduced the amount of sediment available to support wetlands that make up much of the river’s delta, resulting in the loss of several square miles of coastal wetlands each year in Louisiana. Until more information becomes available, it would be premature to comment on the extent to which wetland loss contributed to the devastating effects of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, the committee said.

The projects reviewed by the committee are part of the Corps’ Louisiana Coastal Area (LCA) study, which was released a year ago after the U.S. Office of Management and Budget asked that an earlier study be pared down to focus on projects that could be accomplished in the near future. The governor of Louisiana requested the Research Council’s review of the latest study, the goal of which is “to reverse the current trend of coastal ecosystem degradation.”

The project proposals in the LCA study alone will not achieve that goal, although some will reduce wetland losses in specific areas, the committee said. It noted, however, that the projects in the study are only intended to lay a foundation for more robust efforts to preserve and restore coastal Louisiana; in fact, the LCA study indicates that its projects would only reduce land loss by about 20 percent a year. But by limiting itself to near-term projects that must begin in the next five to 10 years — meaning ones that are already planned — the study precludes consideration of promising projects that have not yet been fully designed. A more comprehensive, systemwide plan — although not necessarily the one proposed earlier by the Corps and the state of Louisiana — for the entire coastal region is needed to more clearly articulate the future distribution of land, the committee concluded.

Nevertheless, because they support a more comprehensive approach, most of the projects proposed in the current study should move forward, the committee said. One exception is the proposal to build an embankment along the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, a project that is expected to reduce land loss by just 0.2 square miles a year despite an estimated cost of more than $100 million. In addition, the Corps currently is studying whether to decommission the outlet as a route for large ships.

The embankment proposal should be re-evaluated, given its slim benefits and the chance that the outlet’s role in navigation may be reduced. On the other hand, the committee called for consideration of an idea to divert the Mississippi River toward the west, a step that could bring sediment to eroding coastal wetlands there.

Levee failure caused massive flooding in and around New Orleans. Scientists say the loss of coastal marshlands that buffer New Orleans from flooding and storm surges may have worsened the impact of Hurricane Katrina. Further, the construction of levees along the Mississippi river delta may have hastened the decline of wetland vegetation along the coast by preventing these ecosystems from recieving the floodwater and mud that they need to survive. Following the storm, the White House was looking into whether it could pin blame on environmentalists for the failure of the levees. |

Conflicting interests among stakeholders are one of the greatest challenges to coastal restoration efforts in Louisiana, and one of the reasons why individual projects have been widely distributed across the entire region, which makes them less contentious. The committee’s call for more synergized projects, particularly where the benefits and costs may have a larger impact on a single area, will require significant popular support. Communicating the restoration goals to the public more clearly using an explicit map of a restored coast will help garner that support, the committee said. Early and active public participation will obviously be needed when restoration plans require the relocation of people and businesses.

The committee found the Corps study’s science and technology program, designed to support the implementation of projects, to be innovative and effective for monitoring results and meeting many of the technical challenges likely to arise. However, it needs to be better integrated into the overall study’s adaptive management process — where decisions about how to proceed are based on the latest evidence and adjusted if necessary — and must include plans to study how stakeholders are responding to the restoration effort. The relative roles of forces driving land loss in specific areas of coastal Louisiana also need to be better understood.

The committee also was asked to identify the potential contribution of Louisiana’s coastal restoration to the national economy, but Corps officials appeared to view their study in terms of environmental restoration rather than economic development, and therefore did not attempt to quantify national economic benefits, which meant the committee could not comment either. It did, however, note that the Corps study presents sufficient data to demonstrate that substantial economic interests are at stake in coastal Louisiana and that these interests have national significance, as underscored by the impact of Katrina. But without agreement on what a map of restored Louisiana will look like, it is difficult to determine how wetland renewal efforts may protect those interests.

The committee’s report was sponsored by the state of Louisiana and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The National Research Council is the principal operating arm of the National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Engineering. It is a private, nonprofit institution that provides science and technology advice under a congressional charter. A committee roster follows.

Copies of Drawing Louisiana’s New Map: Addressing Land Loss in Coastal Louisiana will be available this winter from the National Academies Press; tel. 202-334-3313 or 1-800-624-6242 or on the Internet at http://www.nap.edu.

[ This news release and report are available at http://national-academies.org ]

This is a modified press release from National Academy of Sciences