Amazon headed toward permanent changes?

Recent studies by NASA scientists have found that heavy smoke from Amazon forest fires inhibits cloud formation and reduces rainfall. This finding, combined with other NASA studies suggesting that deforestation can affect regional climate, means that the Amazon rainforest may be on the verge of a significant environmental transformation.

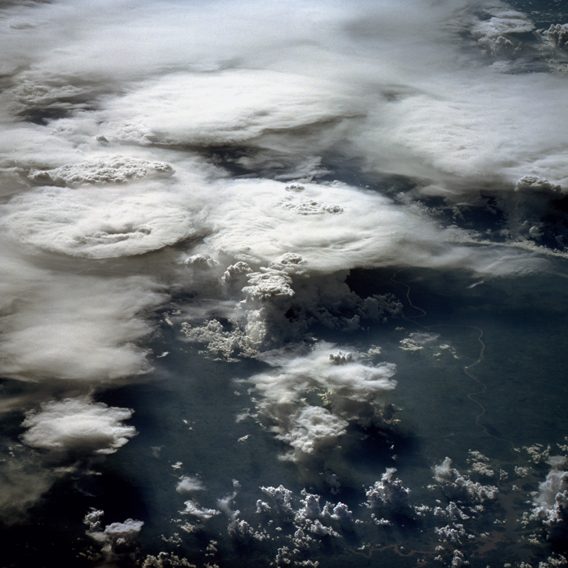

This photograph, acquired in February 1984 by an astronaut aboard the space shuttle, shows a series of mature thunderstorms located near the Parana River in southern Brazil. With abundant warm temperatures and moisture-laden air in this part of Brazil, large thunderstorms are commonplace. A number of overshooting tops and anvil clouds are visible at the tops of the clouds. Storms of this magnitude can drop large amounts of rainfall in a short period of time, causing flash floods. Image STS41B-41-2347 was provided by the Earth Sciences and Image Analysis Laboratory at Johnson Space Center. Additional images taken by astronauts and cosmonauts can be viewed at the NASA-JSC Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth |

The Amazon rainforest plays a critical role in regional weather by contributing moisture to local humidity through transpiration — the process by which plants release water through their leaves. It is estimated that Amazon creates 50-80% of its own rainfall through this process. Thus, as forest is felled, degraded, and cleared there is less heat absorption by vegetation and less moisture is evapotranspired into the atmosphere. The result: fewer rain clouds are formed and less precipitation falls on the forest — NASA researchers confirmed this with their finding that during the Amazon dry season there was a distinct pattern of lower rainfall and warmer temperatures over deforested regions. The forest becomes drier contributing to a positive feedback loop where rainforest is replaced with savanna which transpires less and less moisture and is more susceptible to fires, which in themselves may alter regional climate by inhibiting cloud formation.

Several studies released in the past five years suggest that aerosols — tiny airborne particles of pollution found in smoke from forest fires — have a “semi-direct” effect on climate, causing a reduction in cloud cover and warming the land surface. According to a release from NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, “processes that often create rain in tropical clouds are practically shut off when the clouds are polluted with heavy smoke from forest fires.” The paper’s author, Dr. Daniel Rosenfeld comments “We’ve seen evidence of decreased precipitation in clouds contaminated by smoke, but it wasn’t until now that we had direct evidence showing that smoke actually suppresses precipitation completely from certain clouds.” In his paper, Rosenfeld focuses on observations over Kalimantan, Indonesia during a satellite’s overpass on March 1, 1998 when “the southeastern portion of the island was engulfed in smoke, while the northwestern portion was relatively smoke free. The spacecraft’s radar detected precipitation in smoke-free clouds, but almost none in the smoke-plagued clouds, showing the impact of smoke from fires on precipitation over the rainforest.” Last year a NASA study in the Amazon reached similar conclusions.

Findings could have far-reaching implications

There is serious concern that widespread deforestation in the Amazon could lead to a significant decline in rainfall and could trigger a positive-feedback process of increasing desiccation for neighboring forest cover, reducing its moisture stocks and its vegetation, furthering the drying effect for the region. Eventually the effect could extend outside the region, affecting important agricultural zones and other watersheds. At the 1998 global climate treaty conference in Buenos Aires, Britain, citing a disturbing study at the Institute of Ecology in Edinburgh, suggested the Amazon rainforest could be lost in 50 years due to shifts in rainfall patterns induced by global warming and land conversion. Forest fires will only worse the situation.

Scientists, economists, and politicians alike have a keen interest in how changes in global precipitation affect human activities, such as crop production and the global rainfall weather pattern. More precise information about the links between deforestation, fires, and rainfall is crucial to understanding the global climate and predicting climate change.

WASHINGTON — For the first time, researchers have proven that smoke from forest fires inhibits rainfall. The findings, to be published in the October 15 issue of Geophysical Research Letters, are based on an extensive analysis of data taken from NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) spacecraft.

The study shows that the “warm rain” processes that often create rain in tropical clouds are practically shut off when the clouds are polluted with heavy smoke from forest fires. In these clouds, scientists found, the cloud tops must grow considerably above the freezing level (16,000 feet or 5,000 meters) in order for them to start producing rain by an alternative mechanism. “We’ve seen evidence of decreased precipitation in clouds contaminated by smoke, but it wasn’t until now that we had direct evidence showing that smoke actually suppresses precipitation completely from certain clouds,” said Dr. Daniel Rosenfeld, the paper’s author and a TRMM scientist at the Institute of Earth Sciences, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Scientists have a keen interest in how changes in global precipitation affect human activities, such as crop production, and the global rainfall weather pattern. More precise information about rainfall and its variability is crucial to understanding the global climate and predicting climate change. In his paper, Rosenfeld highlights one specific area: Kalimantan, Indonesia. During the satellite’s overpass on March 1, 1998, the southeastern portion of the island was engulfed in smoke, while the northwestern portion was relatively smoke free. The spacecraft’s radar detected precipitation in smoke-free clouds, but almost none in the smoke-plagued clouds, showing the impact of smoke from fires on precipitation over the rainforest. “It’s important to note that this is not a unique case,” said Rosenfeld. “We observed and documented several other cases that showed similar behavior. In some instances, even less severe smoke concentration was found to have comparable impacts on clouds.”

This research further validates earlier studies on urban air pollution showing that pollution in Manila, the Philippines, has an effect similar to forest fires, according to Rosenfeld. “Findings such as these are making the first inroads into the difficult problem of understanding humanity’s impacts on global precipitation,” said Dr. Christian Kummerow, TRMM project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland.

Raindrops in the atmosphere grow by two means. In the first, called the “warm rain” process, a few cloud drops get large enough to start falling. As they fall, they pick up other cloud drops until they become big enough to fall to Earth as raindrops. The second process requires ice particles and water colder than 32 degrees Fahrenheit (zero Celsius). Ice particles surrounded by this “supercooled” water may grow extremely rapidly as water freezes onto the ice core. As these large ice particles fall, they eventually melt and become raindrops. Scientists have known for some time that smoke from burning vegetation suppresses rainfall, but did not know to what extent until now. Thanks to TRMM observations, scientists are able to see both precipitation and cloud droplets over large areas, including clouds in and out of smoke plumes.

TRMM has produced continuous data since December 1997. Tropical rainfall, which falls between 35 degrees north latitude and 35 degrees south latitude, comprises more than two-thirds of the rainfall on Earth. TRMM is a U.S.-Japanese mission and part of NASA’s Earth Science Enterprise, a long-term research program designed to study the Earth’s land, oceans, air, ice and life as a total system.

Information and images from the TRMM mission are available on the Internet at URL: http://trmm.gsfc.nasa.gov.