Conversion of forest to oil palm plantations in Borneo. Photo by Rhett A. Butler.

Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation could have been reduced by hundreds of millions of tons had a moratorium on new concessions in high carbon forest areas and peatlands been implemented earlier, reported a researcher presenting at a forests conference on the sideline of climate talks in Doha.

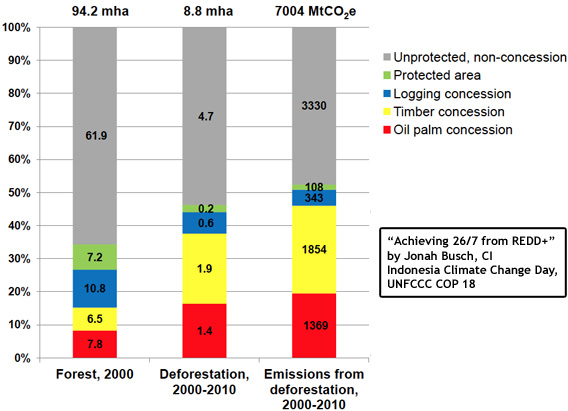

The analysis — presented by Jonah Busch of Conservation International (CI) and based on work by researchers from CI, the Environmental Defense Fund, the World Resources Institute, the University of Maryland, the Woods Hole Research Center, and the Packard Foundation — estimated how much Indonesia would have reduced deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions had it implemented its moratorium on new logging, timber, and palm oil concessions in 2000 instead of 2011. The study concludes that had Indonesia enacted the policy sooner, it could have cut 578 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions by reducing deforestation by 4.7 percent or 414,000 hectares during the period. The reduction would have represented about 8.3 percent of Indonesia’s 8.71 billion tons of total emissions. Had a stricter interpretation of the moratorium (one the applied to all forest and peatland storing more than 150 tons of carbon per ha) been put into place, emissions reductions could have amounted to 1.367 billion tons by saving 1.486 million ha of forest.

Slide from Busch’s presentation. Courtesy of Busch.

Overall the study found that Indonesia lost some 8.78 million hectares of forest and emitted 8.71 billion tons of CO2 (7 billion of which resulted from land use change) during the period. Oil palm and timber (including pulp and paper) concessions represented 38 percent of deforestation but 46 percent of emissions nationwide. The study didn’t evaluate the plantation sector’s impact on forest and peat degradation, an important source of emissions in Indonesia.

The study found that concessioning an area for either timber harvesting or oil palm conversion substantially boosted the deforestation rate: “On average, oil palm concessions increased deforestation by 60%, and timber concessions increased deforestation by 110%,” stated Busch’s presentation. Oil palm concessions lost forest at a rate of 1.6-2.4 percent during the study period, while forest in timber concessions was cleared at 0.3-3 percent per year. Forest in logging concessions declined at 0.5 percent annually.

Going forward, Busch concluded that if Indonesia wants to achieve its target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 26-41 percent from a 2020 baseline, it would need to expand the scope of its current moratorium beyond primary forests and peatlands, to include secondary forests and existing concessions where conversion hasn’t yet taken place. He suggested that a national price on carbon could be be an alternate approach to reducing carbon emissions in Indonesia. For example, he estimated that a compliance-based cap-and-trade system which priced carbon at $2.05 per ton of CO2 emitted would have achieved the same 578 million ton-reduction as the moratorium had it been in effect during the period.

Related articles

Forestry Minister: Indonesia should extend forest moratorium

(11/23/2012) Indonesia should extend its two-year moratorium on new concessions in some 64.8 million hectares of forests and peatlands until its next presidential election in 2014, said the country’s top forest official.

Indonesia could plant 14.5m ha of oil palm in Borneo without further deforestation

(10/31/2012) Indonesia could establish some 14.5 million hectares of oil palm plantations in Borneo without needing to clear rainforest or high-carbon peatlands, finds a new interactive mapping tool developed by the World Resources Institute (WRI).

Will designation of new administrative districts lead to more deforestation in Indonesia?

(10/24/2012) On Monday Indonesia’s House of Representatives moved to establish ‘North Kalimantan’, a new province in Indonesian Borneo. It also voted for four new districts: Pangandaran in West Java, South Coast in Lampung, and South Manokwari and Arfak Mountains in West Papua. While the moves aim to improve governance by boosting local autonomy, they could make it more difficult for Indonesia to meet its deforestation reduction goals if recent trends — detailed in a 2011 academic paper — hold true.

Chart: Indonesia’s forest moratorium

(07/22/2012) Indonesia’s moratorium on new forestry concessions was proposed in 2010 under an agreement with Norway to reduce emissions from deforestation and peatlands degradation. Set to begin Jan 1, 2011, the moratorium was not defined until May 2011 due to battles over what lands would be included. The moratorium was originally expected to include all forest areas, but lobbying by industrial sectors led to significant weakening, resulting in only peatlands and primary forests being included in the moratorium, with loopholes for mining and some energy and food crops.

Deforestation-based policy ‘no longer tenable’ says Indonesian President

(06/17/2012) Indonesia ‘has reversed course’ from a forest policy that drove deforestation in previous decades and is poised to become a leader in ‘sustainable forestry’, asserted Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono during a speech on Wednesday at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Bogor.

Norway: Indonesia’s forest moratorium isn’t enough to meet emissions reduction target

(05/23/2012) Indonesia’s moratorium on new forest concessions will not be enough to meet its 2020 emissions reduction target says the largest backer of the country’s forest and climate action plan.

(02/27/2012) Indonesia’s moratorium on new forest concessions alone “does not significantly contribute” to its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 26 percent from a projected 2020 baseline, concludes a new analysis by the World Resources Institute (WRI). However the study says the moratorium does support the target in the long-term by creating a window for enacting governance reform needed to stop destructive business-as-usual approaches to forest management.

Is the Ministry of Forestry undermining Indonesia’s logging moratorium?

(06/28/2011) Indonesia’s Ministry of Forestry is already undermining the moratorium on new forestry concessions on peatlands and in primary forest areas, alleges a new report from Greenomics-Indonesia. The report, The Toothless Moratorium, claims that a new decree from the Ministry of Forestry converts 81,490 hectares of forest protected under the moratorium into logging areas. The area affected is larger than Singapore.

Indonesia’s moratorium disappoints environmentalists

(05/20/2011) The moratorium on permits for new concessions in primary rainforests and peatlands will have a limited impact in reducing deforestation in Indonesia, say environmentalists who have reviewed the instruction released today by Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. The moratorium, which took effect January 1, 2011, but had yet to be defined until today’s presidential decree, aims to slow Indonesia’s deforestation rate, which is among the highest in the world. Indonesia agreed to establish the moratorium as part of its reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) agreement with Norway. Under the pact, Norway will provide up to a billion dollars in funds contingent on Indonesia’s success in curtailing destruction of carbon-dense forests and peatlands.

Indonesia signs moratorium on new permits for logging, palm oil concessions

(05/19/2011) After five-and-a-half months of delay due to political infighting, Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono finally signed a two-year moratorium on the granting of new permits to clear rainforests and peatlands, reports Reuters.

Is Indonesia losing its most valuable assets?

(05/16/2011) Deep in the rainforests of Malaysian Borneo in the late 1980s, researchers made an incredible discovery: the bark of a species of peat swamp tree yielded an extract with potent anti-HIV activity. An anti-HIV drug made from the compound is now nearing clinical trials. It could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year and help improve the lives of millions of people. This story is significant for Indonesia because its forests house a similar species. In fact, Indonesia’s forests probably contain many other potentially valuable species, although our understanding of these is poor. Given Indonesia’s biological richness — Indonesia has the highest number of plant and animal species of any country on the planet — shouldn’t policymakers and businesses be giving priority to protecting and understanding rainforests, peatlands, mountains, coral reefs, and mangrove ecosystems, rather than destroying them for commodities?