Siberian tiger. John Goodrich (WCS).

“Meanwhile, Trush’s dog, Gitta is racing back and forth, hackles raised and barking in alarm. The tiger is somewhere close by—invisible to the men, but to the dog it is palpably, almost unbearably, present. The men, too, can sense a potency around them—something larger than their own fear, and they glance about, unsure where to look. They are so overwhelmed by the wreckage before them that it is hard to distinguish imminent danger from the present horror.”

—passage from John Vaillant’s The Tiger.

In The Tiger , John Vaillant weaves a haunting and compelling true narrative of men who live—or die—with tigers. No doubt the story itself is on-the-edge of your seat reading. As well, the book provides factual information on the 400 or so Amur Tigers remaining, and the raw milieu that is Primorye, Far East Russia—a wilderness and people unto their own. What is special, transcendent even in this story, however, murmurs uncomfortably in the background. Questions emerge from deep taiga snow, not unlike the unseen Panchelaza Tiger. What exactly is our relationship with apex predators? How do people live with them? How would you live with them in your backyard? What if your pet dog disappeared? As we ourselves are apex predators, are we wise enough, tolerant enough, compassionate enough to share this planet with them? Evidence today points to the contrary, but this can change.

The author, John Vaillant. Photo by: Michael Lionstar. |

The Year of the Tiger has come and gone. 2010 proved that many do actually care about this magnificent animal, be they World Bank heads, former prime ministers, A-list celebrities or millions of private citizens. Tiger imagery abounds in our world in many forms. From Frosted Flakes breakfast cereal, to Tiger Woods, or a pharmaceutical (Viagra directly derives from the ancient Sanskrit word for tiger, Vyaghra), we see these false tigers thrive. Yet, the wild, in–the-flesh ones are rapidly disappearing. Can the Year of the Tiger be every year now, going forward? Can action match goodwill?

INTERVIEW WITH JOHN VAILLANT

Mongabay: The Tiger is about much more than the Amur Tiger. How did you come across this remarkable story and what compelled you to write about it?

John Vaillant: In 2005, a British filmmaker named Sasha Snow made a one-hour documentary about some of the events I cover in the book. This award-winning film is called Conflict Tiger and I happened to see it at the Banff Mountain Festival where I was also presenting. I was hooked from the opening shot and, about 15 minutes into it I felt a bolt of recognition – sudden, exhilarating and terrifying all at once. Thematically speaking, I had visited this country before in my first book, The Golden Spruce . But that true story of humans and nature in collision didn’t have a tiger in it. I couldn’t get ‘Conflict Tiger’ out of my mind and, as soon as I got home, I called the director. Sasha Snow and I work in different media, on different continents, but it was clear that we were tuned to the same frequency. We hit it off immediately, and he encouraged me to go to Russia myself.

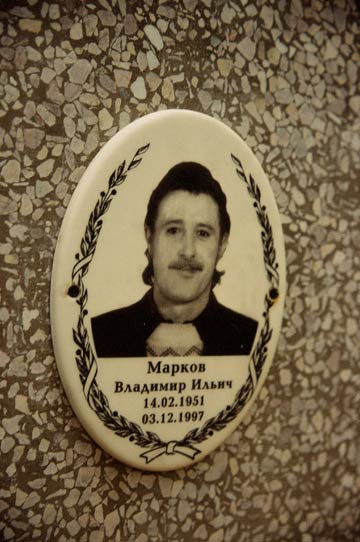

As captivated as I was by the film, I was also left with lingering questions. I wanted to know more about the poacher, Markov, who did not survive to be interviewed, but who left family, friends and tantalizing clues, and I wanted to know more about the tiger’s other victims.

I also wanted to know more about the inspector, Yuri Trush, the man charged with solving these reciprocal crimes against nature and who, in so doing, got caught up in them himself.

And I wanted to try to understand this tiger: its strange and spooky sentience, its frightening capacity for absorbing bullets and holding a grudge, and its apparent preference for only the most dangerous adversaries. What drives an animal like that, I wondered, across the years and miles, through Arctic cold?

Finally, I wanted to understand the desperate circumstances that set this serial tragedy in motion.

Mongabay: John, one of the noteworthy concepts you deal with in the book is the idea that this tiger pre-meditated its attack on Vladimir Markhov. That is, the tiger had the forethought to carry out his mission. Please share with our readers the “unbelievable” course of events that lead to this conclusion.

Vladimir Markov. Photo by: John Vaillant. |

John Vaillant: One of the most compelling—and chilling—elements of this story is the single-minded way in which the tiger set about liquidating Vladimir Markov, the unemployed logger-turned-poacher who shot and wounded this tiger at point-blank range. Because he was shot at close range, the tiger was able to identify Markov and track him, which he did. When he got to Markov’s isolated cabin, he investigated and destroyed Markov’s belongings in an eerily systematic way, the aftermath of which was recorded on video by investigators. Markov managed to escape, but the tiger waited, and waited – like a hit man—until Markov was compelled to return (it was his cabin after all). Although Markov was armed and ready, he was not as ready as the tiger who confronted him face to face, and killed him by his front door. So it begins…

Mongabay: Out from this “tiger consciousness” if you will, you bring to our awareness the concept of “Umwelt.” This pervades the landscape of Primorye, the taiga, and its people. Could you share with Mongabay readers the idea of “umvelt”?

John Vaillant: Umwelt is a term coined more than a century ago by an Estonian physiologist named Jakob von Uexkull who is considered one of the fathers of ethology (also known as behavioral ecology). Ethology is a young discipline whose goal is to study behavior and social organization through a biological lens. “To do so,” wrote Uexkull, “we must first blow, in fancy, a soap bubble around each creature to represent its own world, filled with the perceptions which it alone knows. When we ourselves then step into one of these bubbles, the familiar…is transformed.” Uexkull called this ‘bubble’ the umwelt, a German word that he applied to a given animal’s subjective or “self-centered” world. An individual’s umwelt exists side by side with the Umgebung—the term Uexkull used to describe the objective environment, a place that exists in theory but that none of us can truly know given the inherent limitations of our respective umwelten. For me, umwelt and umgebung offered a helpful framework for exploring and describing the experience of other creatures, which is one of the central themes in The Tiger.

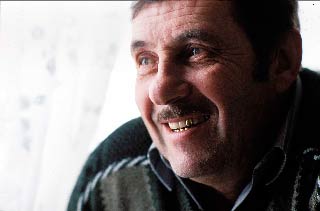

Mongabay: Surely if one could tick off a check list of qualities one would like in a wildlife ranger and protector of the Amur Tiger and its habitat, that man would be Yuri Trush. How would you describe him? It seems as though if we had a handful of Yuri Trushes, and the political will to support men like him, conservation of wildlife around the world could really take a leap forward.

Yuri Trush. Photo by: Sasha Snow. |

John Vaillant: In the mid-1990’s, Yuri Trush was a chief inspector with Inspection Tiger, the regional agency charged with investigating and resolving these attacks. Trush is one of the most inspiring and courageous men I’ve ever met. In my acknowledgment to him, I wrote, “On a daily basis, Trush manifests the verity that faith is a physical act.” It is this combination of faith and action, this fearless and relentless dedication, that is required to protect what we love. Trush has risked his life repeatedly to protect tigers, their prey, and the human beings who share the tiger’s habitat in a respectful way. There are others like him, but they are rare individuals. As strong as we may feel our convictions to be, very few of us are willing to lay down our lives for others, especially other species. Trush sets a potent example of what we can be and do, indeed what we must be and do, if we are going to stem the tide of extinction currently sweeping the planet.

Mongabay: As an author of non-fiction where exhaustive research and intimacy with the subject are required, it happens sometimes that the intensity of the work and its characteristics can seep into one’s being. How has creating “The Tiger” affected you? Changed you?

John Vaillant: First and foremost, it has given me a much deeper appreciation for tigers, and animals in general. I had to learn a lot (from some excellent teachers) in order to write this book, and it required me to explore the concept of Umwelt deeply. I have emerged from this experience with the conviction that empathy for others, no matter what the species, nationality, etc., is the key to our mutual survival, not to mention joy.

One of things I was most moved by was the generosity of those who were so deeply impacted by these events. Lives were changed forever by these attacks, many for the worse. Nonetheless, the survivors, many of whom are desperately poor, invited us into their homes and lives and offered what they had, whether it was tea, a meal, or very personal information. These experiences made me put myself and my own willingness to give under much tougher scrutiny.

Mongabay: Would you share with Mongabay readers some of these unheralded tiger conservancies that you worked with and are making a difference on the ground in Primorye?

John Vaillant: In addition to well known heavies like WWF and Panthera, there are some terrific smaller organizations working bravely and effectively to ensure a safe and healthy future for Amur tigers. For more information on who and how to help, please visit: The Tiger Book

Mongabay: The Tiger is the story of the world’s largest cat enacting revenge on its human persecutors. No doubt, tigers are beautiful and awesome, but their run-ins with humans, and people’s livestock, are often fraught with conflict, and sometimes, death. Why should the “powers that be” work to save such an animal?

John Vaillant: One of the fundamentals of leadership is stewardship, and that includes the wise and compassionate protection of the resources and other beings in your charge. Large predators present a unique challenge in this regard, in part because, until very recently, protecting ourselves from such animals has been a high priority along with meeting basic needs like shelter and food. To this day, we are hard-wired to fear, if not despise, creatures capable of destroying us. That said, the tide has so clearly turned in our ‘favor’ that the same animals who may have once terrified us are now in the greatest need of our protection. This is the price, if you will, of our overwhelming success. The critically endangered Amur tiger and leopard are two prime examples: their future is literally in our hands.

What is so important to understand is that such predators do not willingly seek us out. Conflicts with humans and livestock are almost always an indicator of ill-health—on the part of an individual animal (or human), or of the entire ecosystem. Given sufficient habitat and prey, predators would much prefer to stay far away from humans. Today, human beings living in predator habitat are often the poorest, most vulnerable members of society, and so it is up to the leadership to help these individuals in the necessary effort to coexist with the few remaining predators. The best way to do this is to ensure that the surrounding landscape is intact, including the prey base. Such enlightened stewardship has the added benefit of contributing to the overall health of the ecosystem, which is crucial to everyone’s survival.

To donate: Protect Tigers.

To learn more about John Vaillant and follow future projects: John Vaillant website, Facebook page, and Twitter.

Related articles

Plight of the Bengal: India awakens to the reality of its tigers—and their fate

(06/06/2010) Over the past 100 years wild tiger numbers have declined 97% worldwide. In India, where there are 39 tiger reserves and 663 protected areas, there may be only 1,400 wild tigers left, according to a 2008 census, and possibly as few as 800, according to estimates by some experts. Illegal poaching remains the primary cause of the tiger’s decline, driven by black market demand for tiger skins, bones and organs. One of India’s leading conservationists, Belinda Wright has been on the forefront of the country’s wildlife issues for over three decades. While her organization, the Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI), does not carry the global recognition of large international NGOs, her group’s commitment to the preservation of tigers, their habitat, and the Indian people who live with these apex predators, is one reason tigers still exist.

Tiger summit reaches bold agreement and raises $300 million

(11/24/2010) The summit to save the world’s biggest cat, and one of the world’s most popular animals, has agreed to a bold plan dubbed the Global Tiger Recovery Program. Meeting in St. Petersburg, 13 nations have set a goal to double the wild tiger’s (Panthera tigris) population worldwide by 2022. Given that tiger numbers continue to decline in the wild, this goal is especially ambitious, some may even say impossible. However, organizations and nations are putting big funds on the table: around $300 million has already been pledged, including $1 million from actor, and passionate environmental activist, Leonardo Dicaprio.

Rebuttal: Slaughtering farmed-raised tigers won’t save tigers

(11/18/2010) A recent interview with Kirsten Conrad on how legalizing the tiger trade could possibly save wild tigers sparked off some heated reactions, ranging from well-thought out to deeply emotional. While, we at mongabay.com were not at all surprised by this, we felt it was a good idea to allow a critic of tiger-farming and legalizing the trade to officially respond. The issue of tiger conservation is especially relevant as government officials from tiger range states and conservationists from around the world are arriving in St. Petersburg to attend next week’s World Bank ‘Tiger Summit’. The summit hopes to reach an agreement on a last-ditch effort to save the world’s largest cat from extinction.

(11/18/2010) A recent interview with Kirsten Conrad on how legalizing the tiger trade could possibly save wild tigers sparked off some heated reactions, ranging from well-thought out to deeply emotional. While, we at mongabay.com were not at all surprised by this, we felt it was a good idea to allow a critic of tiger-farming and legalizing the trade to officially respond. The issue of tiger conservation is especially relevant as government officials from tiger range states and conservationists from around the world are arriving in St. Petersburg to attend next week’s World Bank ‘Tiger Summit’. The summit hopes to reach an agreement on a last-ditch effort to save the world’s largest cat from extinction.

Would legalizing the trade in tiger parts save the tiger?

(11/15/2010) Just the mention of the idea is enough to send shivers down many tiger conservationists’ spines: re-legalize the trade in tiger parts. The trade has been largely illegal since 1975 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The concept was, of course, a reasonable one: if we ban killing tigers for traditional medicine and decorative items worldwide then poaching will stop, the trade will dry up, and tigers will be saved. But 35 years later that has not happened—far from it. “Words such as ‘collapse’ are now being used to describe the [tiger’s] situation both in terms of population and habitat. Wild tiger numbers continue to drop so that we have about 3,500 today across 13 range states occupying just 7% of their original habitat. It’s universally acknowledged that we’re losing the battle,” Kirsten Conrad, tiger conservation expert, told mongabay.com in a recent interview.

(11/15/2010) Just the mention of the idea is enough to send shivers down many tiger conservationists’ spines: re-legalize the trade in tiger parts. The trade has been largely illegal since 1975 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The concept was, of course, a reasonable one: if we ban killing tigers for traditional medicine and decorative items worldwide then poaching will stop, the trade will dry up, and tigers will be saved. But 35 years later that has not happened—far from it. “Words such as ‘collapse’ are now being used to describe the [tiger’s] situation both in terms of population and habitat. Wild tiger numbers continue to drop so that we have about 3,500 today across 13 range states occupying just 7% of their original habitat. It’s universally acknowledged that we’re losing the battle,” Kirsten Conrad, tiger conservation expert, told mongabay.com in a recent interview.

Authorities confiscated over 1000 tigers in past decade

(11/09/2010) Highlighting the poaching crisis facing tigers, a new report by the wildlife trade organization, TRAFFIC, found that from 2000-2010 authorities have confiscated the parts of 1,069 tiger individuals, many of them dead. The tigers, or their body parts, were confiscated from 11 of the species’ 13 range countries, according to the report entitled Reduced to Skin and Bones. Yet the number only hints at the total number of tigers (Panthera tigris) vanishing in the wild due to the illegal trade in tiger parts for traditional Asian medicine and decorative items, such as skins.

After months on the run, man-eating tiger caught

(10/28/2010) A male Bengal tiger that killed eight people was captured after a months-long chase by officials with India’s Forest Department and biologists with the local conservation organization, Wildlife Trust of India (WFI), in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. After avoiding laced bait and tranquilizer darts, the tiger was finally trapped by officials earlier this month. Even after being tranquilized three times, the animal still lashed out, injuring several villagers who had begun throwing rocks at it. Eventually, though, the hunt for the cat ended with its capture.

Interpol pounces on tiger traffickers

(10/11/2010) INTERPOL, the world’s largest international police organization, is stepping up the fight to end the illegal tiger trade.

Hope remains for India’s wild tigers, says noted tiger expert

(09/30/2010) As 2010 marks ‘The Year of the Tiger’ in many Asian cultures, there has been global interest in the long-term viability of tiger populations in the wilds of Asia. Due to increasing pressures on remaining tiger habitats and a surge in demand for tiger parts from traditional medicine trades, many conservation experts consider the current outlook for wild tiger populations bleak. Dr Ullas Karanth of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) India does not share this view. He believes that a collaboration of global and local interests can secure a future for tigers in the wild.

Tigers successfully reintroduced in Indian park

(09/27/2010) Poachers killed off the last Bengal tiger in India’s Sariska Tiger Reserve in 2004. Four years later, officials transferred three tigers from Ranthambhore National Park to Sariska in an attempt to repopulate the park with the world’s biggest feline. A new study in mongabay.com’s open-access journal Tropical Conservation Science evaluates the reintroduction by tracking radio-collared tigers and studying their scat.

Tigers discovered living on the roof of the world

(09/20/2010) A BBC film crew has photographed Bengal tigers, including a mating pair, living far higher than the great cats have been documented before. Camera traps captured images and videos of tigers living 4,000 meters (over 13,000 feet) in the tiny Himalayan nation of Bhutan.

Saving wild tigers will cost $82M/year

(09/15/2010) The cost of maintaining the planet’s 3,500 remaining wild tigers is around $80 million a year, according to a new study published in the journal PLoS Biology.